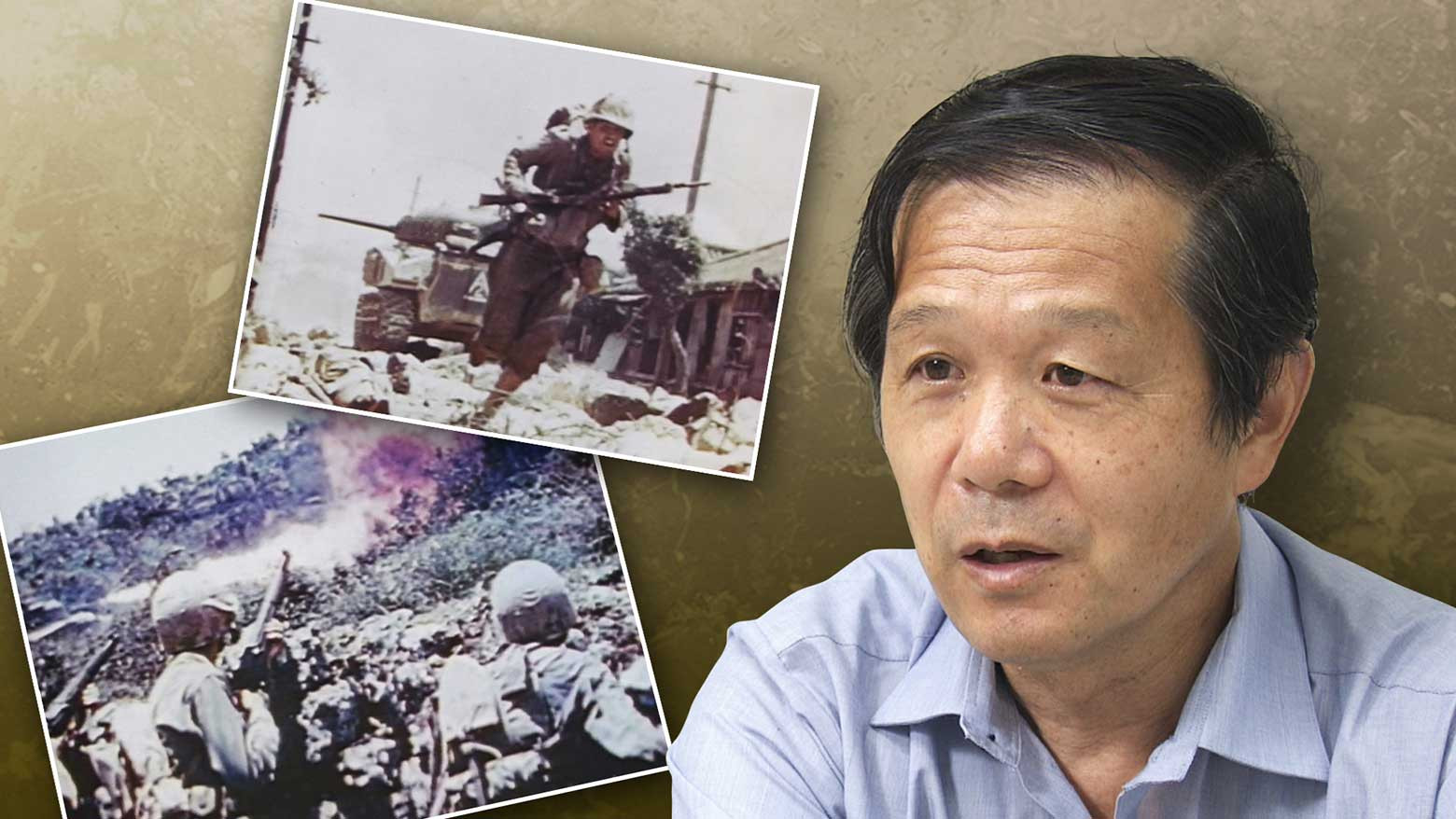

Ushijima Sadamitsu was a schoolteacher in Tokyo for about forty years. But these days, his most important pupil is himself. He’s been making frequent trips to Okinawa to learn about the fighting for nearly thirty years.

He keeps returning to one sight in particular: the former headquarters of Japan’s 32nd Army. The kilometer-long complex of tunnels lies 30 meters below Shuri Castle in the city of Naha. The site is not open to the public, as there are concerns it may collapse.

Army staff chose the location because they believed the ground was firm enough to withstand heavy US shelling. The site also provided ideal vantage points for spotting American soldiers as they approached from several miles away.

About 1,000 military personnel and conscripts were stationed in the compound. It was the site where every command for troops on the ground was made. And the man in charge was Sadamitsu’s grandfather, General Ushijima Mitsuru.

Today, the general is known as the military leader who caused countless civilian deaths in Okinawa, and this legacy has always weighed on Sadamitsu. For years, he avoided visiting Okinawa. But when he finally made the trip in 1994, he says it changed his life.

Sadamitsu was on a tour of the area with several colleagues, part of an effort to promote peace studies, when the guide noticed he had the same name as the infamous commander.

“My first thought was, ‘Oh no, I’ve been discovered,’” Sadamitsu says. But after he revealed his secret, he was surprised by the guide’s reaction.

“He told me to look into my grandfather’s life and said it would help me.”

The encounter started Sadamitsu down a new path. He began to make regular visits to the island, interviewing people who survived the fighting.

The late Miyagi Kikuko was one of the people who spoke to Sadamitsu. She was drafted into the Hiyemuri Student Corps at the age of sixteen to work as a military nurse. Many of her classmates died in shelling attacks, while others killed themselves with hand grenades after being surrounded by enemy troops.

Miyagi told Sadamitsu that she remembers meeting his grandfather while working at a makeshift hospital in a cave.

“I had the American book Gone with the Wind with me,” she said. “The commander noticed it, and I thought he was going to yell at me. But he asked what I was reading, and then left. It stuck in my mind. I thought he was very kind.”

The more Sadamitsu heard about his grandfather, the more difficult he found trying to reconcile the gentle depictions of the man with the horrific decisions he made on the battlefield. As the American troops intensified their offensive, the general ordered his troops to abandon the headquarters and retreat to the southern part of the island. This was where many civilians had evacuated to. The general killed himself one month after ordering the retreat. By some estimates, his decision is believed to have caused 46,000 civilian casualties in the final weeks of fighting.

“I think my grandfather knew what would happen if he retreated south,” Sadamitsu says. “It’s hard for me to understand why he did that. If he was truly a good or honorable commander, he would’ve come to a different decision.”

Efforts to preserve the subterranean headquarters have gained steam since last fall, when Shuri Castle was destroyed in a fire. A surface level restoration is planned, but survivors and historians are calling for efforts to maintain the facility lying underneath.

They have also organized a civic group to lobby for the site to be made public. The prefectural government says it will set up a committee to look into the possibility.

Sadamitsu supports the efforts, saying, “The headquarters is a place where we can show people what the war in Okinawa was like, and why so many civilians died.”

With nearly thirty years of research under his belt, Sadamitsu is now something of an expert on the history of the headquarters. But he says he wants to keep his role in the civic group’s activities limited because he doesn’t want his commitment to be misconstrued as an effort to preserve his grandfather’s legacy.

The restoration project could cost millions of dollars. But Sadamitsu believes the stories held within in the walls of the headquarters—both about the fighting, and his grandfather’s role in it—are worth preserving, whatever the price.