Legacy of the Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a secretive research and development program to produce the first nuclear weapons. Starting in 1939, it involved the world's top scientists and engineers and in total half a million Americans at various sites across the US.

Within a month of the Trinity test, two bombs -- Little Boy and Fat Man -- were dropped on the two cities in Japan, killing tens of thousands of people. Following the end of the project in 1946, some sites have been closed, while others remain as defense and security-related facilities.

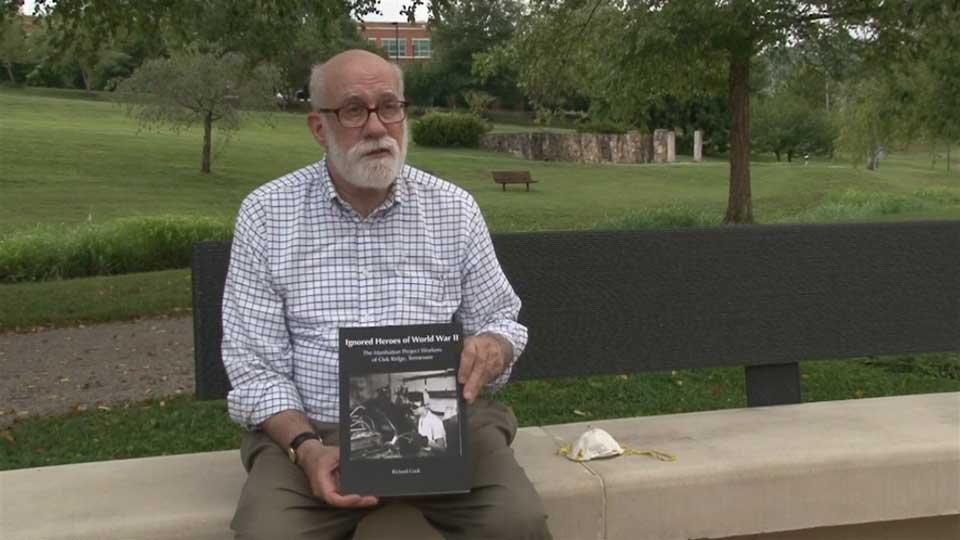

In the US, opinions have been shifting over the years on the use of the bombs. A 2015 Pew research survey found that 56 percent of Americans believed that the dropping of the atomic bombs was justified -- a seven-point drop from 1991. Among younger generations, it was even lower. Some residents of the Manhattan Project host communities feel frustrated by this trend. Richard Cook, who authored the book "Ignored Heroes of World War II: The Manhattan Project Workers of Oak Ridge, Tennessee," says he wishes the project was talked about in a more positive way. He wants the men and women who worked on it to be recognized for their efforts in bringing about the end of the war.

Manhattan Project sites as a Historical Park

In 2015, some parts of the former Manhattan Project sites in three states -- New Mexico, Washington and Tennessee -- were designated as a national historical park managed by the government's National Park Service. Staff members discussed how to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombings and came up with the idea to solicit Japanese-style paper cranes with written messages of peace. The collection will be stored in a time capsule to be opened in 2045, the 100th anniversary.

In a telephone interview with NHK, Superintendent of the Manhattan Project Historical Park Kris Kirby said: "The National Park Service is striving to be America's storytellers. We don't necessarily advocate for any specific agenda or take a position, but make efforts to provide an objective and comprehensive narrative, part of which often includes difficult or uncomfortable pieces of American history." She believes it would be poignant a century after the bombings to encourage people to look at what others were thinking about in 2020.

Responding to the call in the US and Japan

New York-based filmmaker Amy Guggenheim made a crane with her 10-year-old son Jeremy. She wishes that in 25 years Jeremy will be living in a more peaceful and accepting world and wrote "Dare to care, dare to share." She explains, "If we dare to care, we reach past boundaries of separation, and recognize our well-being can be tied to each other's gain, which we can share with others."

Japan tourism expert Kate Ulberg lives near Lake Tahoe. Her work as a mountain guide brought her to Japan for the first time in the 1980s. Her WWII veteran father had objected because it was once America's enemy. But by spending time getting to know people and culture, "Japan has become a big part of my life."

Digital storyteller Ari Beser is the grandson of Jacob Beser, who was the only US serviceman to fly on both B-29s carrying Little Boy and Fat Man. Seventy years later, Ari visited Japan to meet numerous atomic bomb survivors and told their stories through his book and documentary film "The Nuclear Family." His message on the crane is "Black Lives Matter" -- he hopes that "the crane is revealed to a world that loves and embraces black bodies and culture the way it has embraced Japanese culture."

Historian Amber Beirele of Boise, Idaho says her five-year-old son Malcolm recently started understanding the concept of war and conflicts and knows his great-grandfather served in World War Two. She wants to teach her children to pause and reflect, as "it's sometimes too easy to harshly judge the past, too easy to romanticize it and say no one made mistakes."

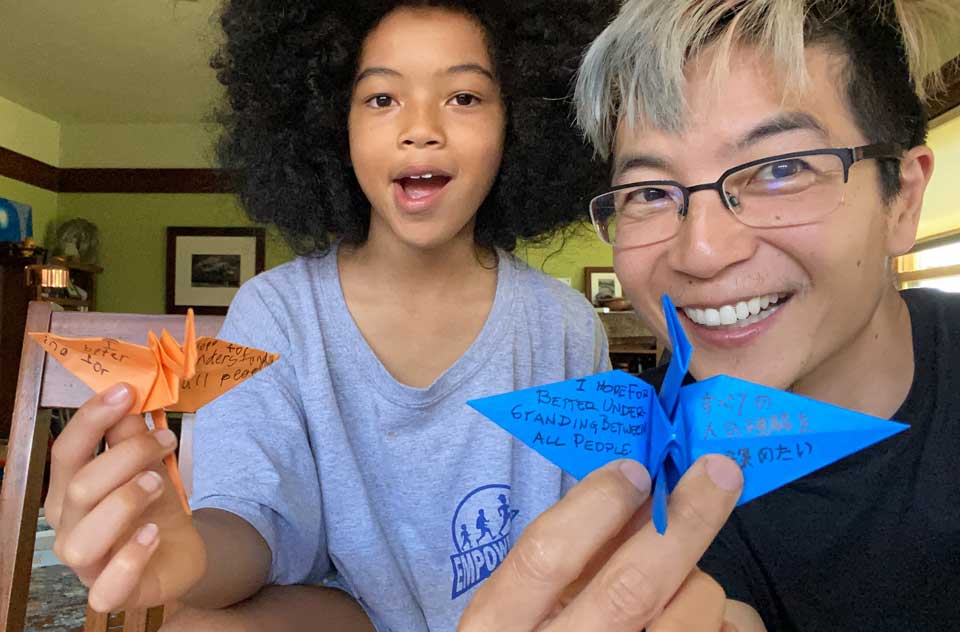

Californian app developer Mach Kobayashi recently did a drawing of a relative he never met. His great uncle Kaz, the son of a Japanese immigrant, served in the US Army and was killed in action in Italy in 1944, while the rest of his family were sent to internment camps. Kobayashi and his son Dyson hope for better understanding between all people.

In Hiroshima, Ogura Keiko joined the crane project. She turned eight years old two days before the atomic bombing in 1945. She was knocked down by the blast, but miraculously sustained no serious injuries. She witnessed heaps of burned bodies, a scene that left a deep psychological trauma that she chose not to share with anyone for over half a century. Ten years ago, however, she decided it was time to talk. Now she gives testimony in English to foreign students and journalists. She hopes her wish "No Nukes Forever" will have been fulfilled by 2045.

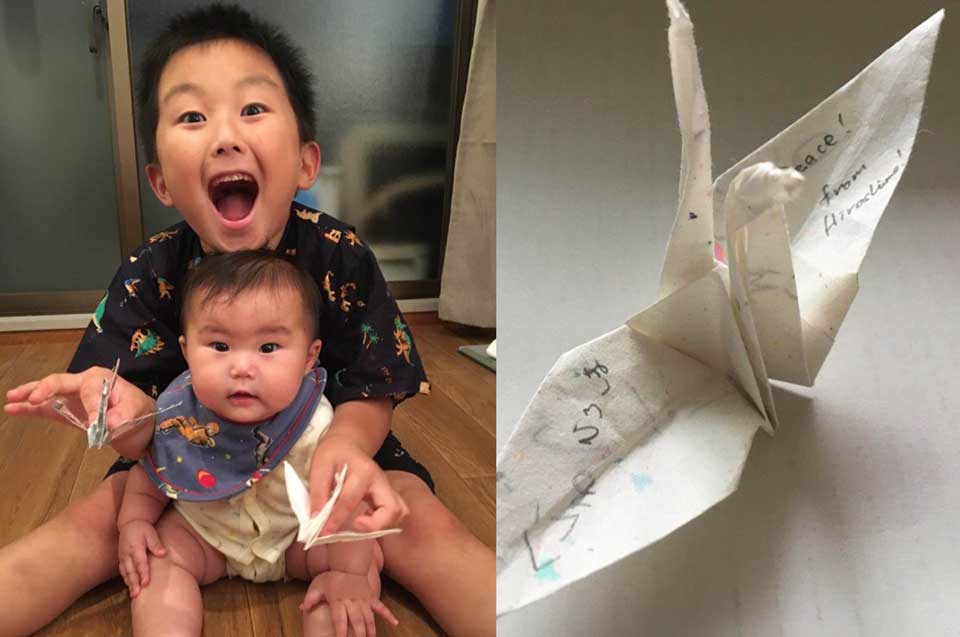

Six-year-old Hirao Ryuhei and his baby sister Setoka are the grandchildren of a hibakusha in Hiroshima. When they grow up, their father Junpei wants them to know about Hiroshima's history, to be aware of issues of peace and nuclear weapons and to make many friends within Japan and across the world. Ryuhei wrote "Heiwa" (meaning "Peace") on the white crane.

All the cranes made for the 75th anniversary of the bombings will be collected and archived by the Manhattan Project National Historical Park, with the messages of peace shared now, and saved for the future.