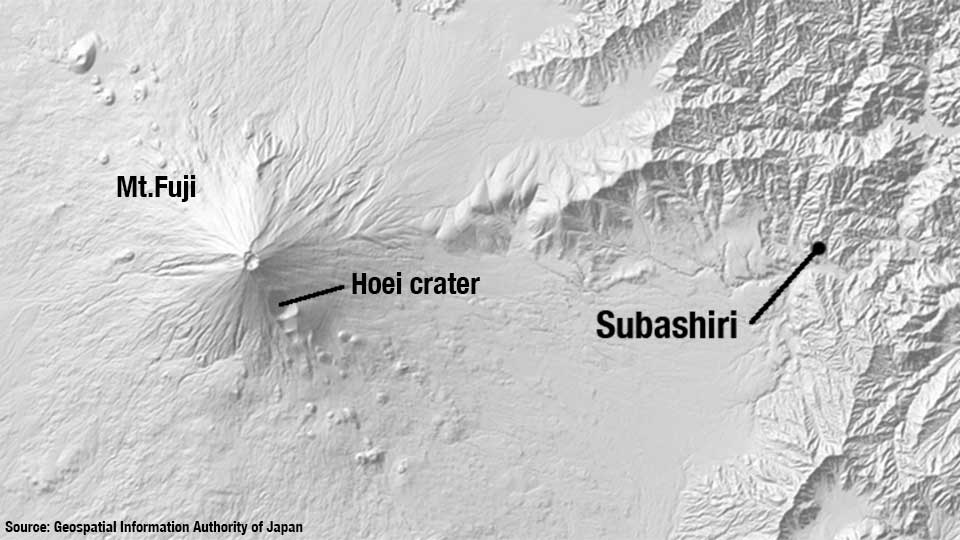

The Hoei eruption began on December 16, 1707, during Japan's Edo period. The blast was centered on the southeastern slope of Mount Fuji, and the event lasted until January the following year. Ancient records say the village of Subashiri, about 10 kilometers from the crater, was the worst-hit community. It was home to Fujisengen Shrine, which served as the gateway to a mountain trail. After those fateful weeks in winter, nobody would pass through again.

The records also tell us nobody was killed, but that's not to say the disaster didn't take its toll on the lives of the locals. Thirty-seven houses were destroyed in a fire triggered by scorching volcanic material. The remaining 39 structures, buckling under the weight of debris piled as high as three meters, collapsed in a series of earthquakes.

Everything was blanketed in thick ash. Authorities decided to rebuild on top, instead of removing what lay beneath. Subashiri became legendary, a village laid to waste by Japan's most famous natural wonder.

In June last year, a project kicked off to shed more light on the disaster. It's being led by officials from Oyama Town, which stands where Subashiri once did, and a team of researchers including archaeologist Sugiyama Cohe and volcanologist Fujii Toshitsugu, both from the University of Tokyo.

They begin their search with a land survey. Using ground-penetrating radar, they locate what could be the remains of house-like structures. About 20 centimeters below the surface, they discover a two-meter-thick layer of volcanic rock known as scoria.

Digging a little deeper reveals a 15-centimeter-thick layer of pumice stone and, crucially, what appears to be two charred house pillars measuring about 10 centimeters in diameter. Fragments of what are thought to be burnt walls and thatched roofing are also nearby. And a little further south, a ridged field.

In the search for Subashiri, these telltale signs of a settlement are the first of their kind.

The significance was not lost on Sugiyama. "The story that Subashiri was buried under volcanic ash is legendary," he says. "Confirming the village did actually exist is a major archeological accomplishment."

The team went on to examine pumice stones found near the pillars. Their inner sides were partly reddened, something Fujii attributes to oxidation as they fell to the ground. He believes it is these stones, which would have been hundreds of degrees Celsius at the time of the eruption, that charred the houses of Subashiri.

Lessons from Pompeii

For the past 18 years, Sugiyama has been taking annual trips to southern Italy, where he's part of an archaeological survey involving Mount Vesuvius. It famously erupted in 79 A.D., burying the city of Pompeii and killing about 2,000 people. The volcano is still active, posing a threat to the city of Naples and its population of about one million. The archaeological survey informs the disaster-planning measures being taken by Italy's Civil Protection Department.

Sugiyama wants to use the experience he's gained in Italy to boost Japan's ability to deal with volcanic eruptions. "Learning more about disasters of the past can be very significant in terms of devising new measures," he says.

A government panel believes an eruption on Mount Fuji is less about "if," and a lot more about "when." If it were on a similar scale to the last one, the damage and disruption could be severe. Roads, railways and airports in and around Tokyo would be affected, even as far as 90 kilometers away from the blast. The panel warns that rain mixed with volcanic ash could damage the power grid, resulting in massive blackouts.

Meanwhile, the team researching the fate of Subashiri continues to present its findings – hopefully, to as large an audience as possible. "If people view the remains of the charred houses, they will think more seriously about disaster preparedness," Fujii says. "Seeing things first-hand will surely resonate more deeply."