The two doctors allegedly administered a fatal drug to 51-year-old Hayashi Yuri at her apartment in Kyoto City last November. An autopsy found non-commercially available barbiturates in her body and listed the cause of death as acute poisoning.

Okubo and Yamamoto were identified through security camera footage, which showed them visiting Hayashi on the day her condition was reported to have suddenly worsened. Neither of them was her primary care physician.

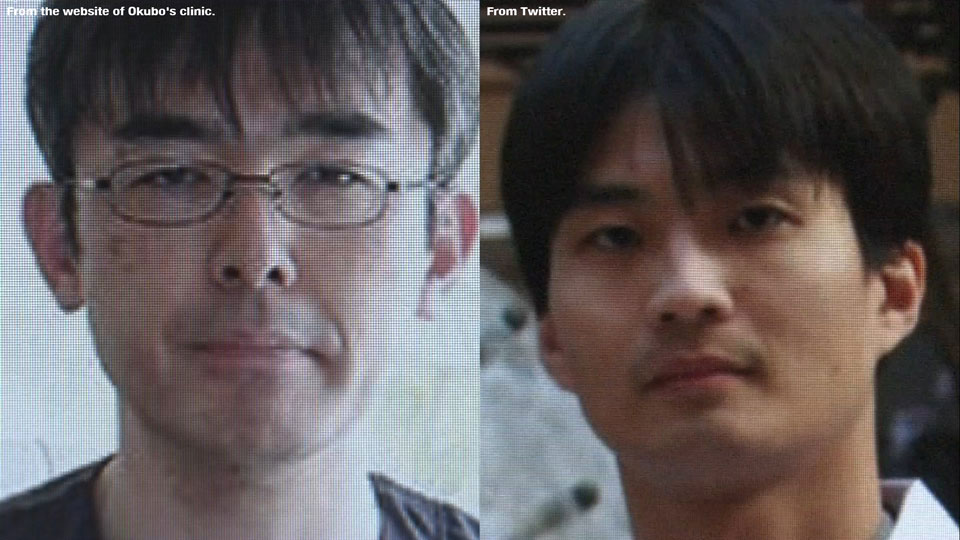

Okubo runs a clinic for respiratory and psychosomatic medicine in Natori City in the northeastern prefecture of Miyagi. The clinic also provides hospice care. Prior to starting his private practice, Okubo worked for the Health Ministry for more than seven years.

Yamamoto runs a clinic in Tokyo. The relationship between the two men was not immediately known.

Hayashi was diagnosed with ALS in her 40s. The neurological disease gradually weakens muscles, reducing the patient’s ability to move, speak, and even breathe. There is no known cure.

Hayashi lived alone in her apartment, getting by with the support of a helper. She communicated using eye-tracking software on a computer.

She often posted on Twitter and police say her posts indicate she had a clear desire to end her life.

“Every day is humiliating and miserable. I can't endure it. Please let me euthanize,” she wrote in one Tweet.

In another post, she wrote, “For 7 years, I've been consistently saying that I want to end all this.”

And in the month she died, she wrote, “It is not selfish to pursue the right to die.”

Hayashi’s father says he was aware of how much his daughter was suffering.

“She was shocked and depressed, asking herself why she had to be sick,” he said. “If I knew what she was about to do, I would have definitely stopped her. But I also wanted to respect her feelings.”

Police believe Hayashi met the two doctors through social media.

Sources say she started communicating with Okubo around December 2018 and that they continued to message until November 2019, three weeks before her death.

In one message, Hayashi hinted at her wish to be euthanized. Okubo wrote back, “The work is simple. If I knew I wouldn’t be prosecuted, I would like to help you.”

Hayashi replied, “I am so happy, I’m crying.”

In another message, Okubo wrote, “Would you like to be transferred to my clinic? I will help you find a natural end of your life.”

Illegal in Japan

Japanese doctors are not allowed to directly administer potentially fatal drugs, or offer prescriptions for such drugs to a patient.

However, cutting off life-support measures can be approved if certain provisions, including clear consent from the patient, are met. The guidelines also require medical workers to thoroughly discuss with the patient and their family members, among other steps, to prepare the patient to make the decision.

Doctors in Japan have been held criminally responsible in the past for deaths of terminally ill patients. In 1991, a doctor at a hospital in Kanagawa Prefecture was charged with homicide after he gave potassium chloride to a patient with terminal cancer. He was asked to do so by a family member.

Euthanasia is legal in a number of countries, including the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Canada, and Colombia. Switzerland and some states in the United States allow doctors to prescribe drugs to assist patient suicide.

However, associate professor Ando Yasunori of Tottori University School of Medicine, a bioethics expert, says the Hayashi case would not be legal even in countries like the Netherlands. Ando says these countries have strict measure in place to prevent doctors from taking such a course of action so quickly and easily.

He adds he hopes the case will shed light on another important issue—the lack of support to help patients with incurable diseases live with dignity.

“Right now, there isn’t enough support in society for these people who are unable to move their bodies and can’t find a purpose for their lives,” Ando says. “Patients are receiving an insufficient level of support, and this has to change.”