In April, the Japanese government implemented a nationwide state of emergency to curb the spread of the coronavirus, asking businesses to limit operations. The measure devastated the economy, leading to a historic first quarter GDP contraction of an annualized 3.4% in real terms and has taken a heavy toll on the country’s labor market.

39-year-old Yamada Kazuaki used to work part-time at a food services company in the northern city of Sendai, making about $1,400 a month. But he was let go amid the coronavirus outbreak. Unable to pay his rent, he ended up on the street.

He has been going to the employment office in search of work but has had no luck. Opportunities are limited and competition is fierce. For now, he is collecting garbage for a few dollars a week.

According to the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, just over 66 million people were recorded as being employed in April, a decline of 800,000 from a year ago. Of these, 20.19 million were non-regular employees, including dispatch and part-time workers, down 970,000 from a year ago. This is the largest dip since comparable data became available in January 2014.

Many businesses, particularly in the accommodation and restaurant industries, have for years struggled with a chronic labor shortage, driven by the country’s rapidly aging society. The coronavirus has turned the problem on its head, with these same businesses unable to hire due to the decline in economic activity.

A restaurant in Tokyo’s Chiyoda Ward was hoping to hire new staff in March. But the manager says a 90% plunge in sales forced him to abandon that plan.

“The virus had a greater impact than I expected,” he says. “I can’t see a future for us at the moment.”

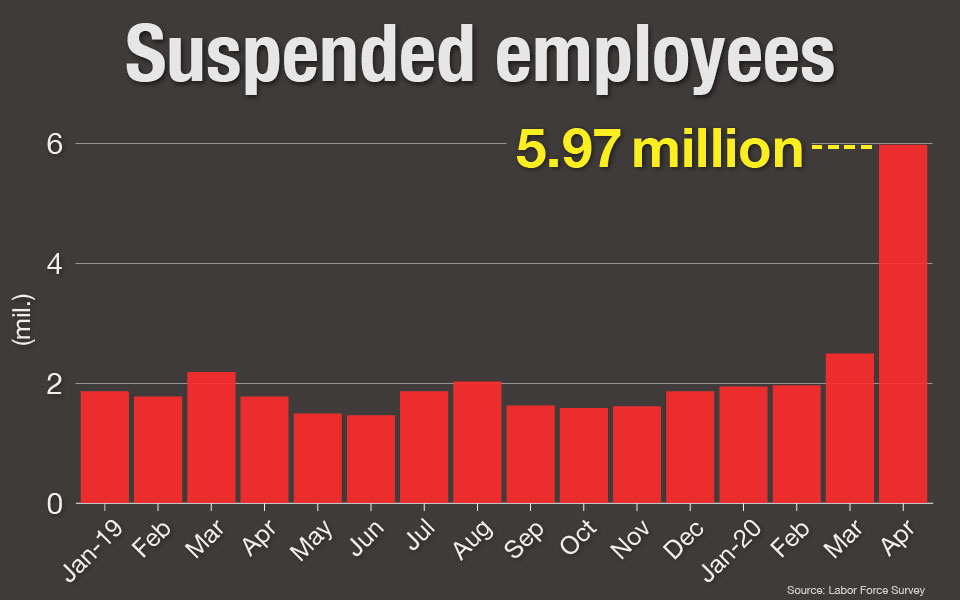

Hoshino Takuya, an economist at Daiichi Life Research Institute, says the worst is yet to come, with nearly 6 million people who are currently suspended from their jobs likely to add to the unemployment figures.

“Companies will try to retain these workers for as long as they can,” he says. “But eventually they will have to cut jobs and this will make the labor market even worse.”

For now, Yamada, the former food services worker, survives on aid from a local nonprofit that supports the homeless. The group walks through Sendai, handing out rice balls and cartons of miso soup to people living in parks, underground passageways, and on the streets.

According to the organization, the majority of the homeless are 60 and older. But due to the economic damage caused by the coronavirus, many younger people are starting to appear on the streets as well.

“Yamada’s situation is not unique,” says Aoki Yasuhiro, the president of the group. “Young people are heavily affected by the situation and face a real risk of ending up on the streets."