The POW's experience

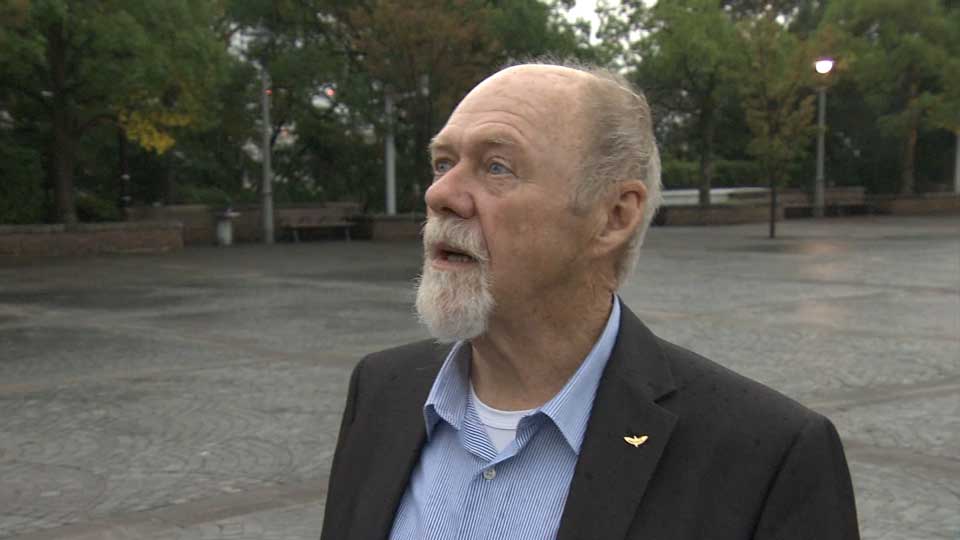

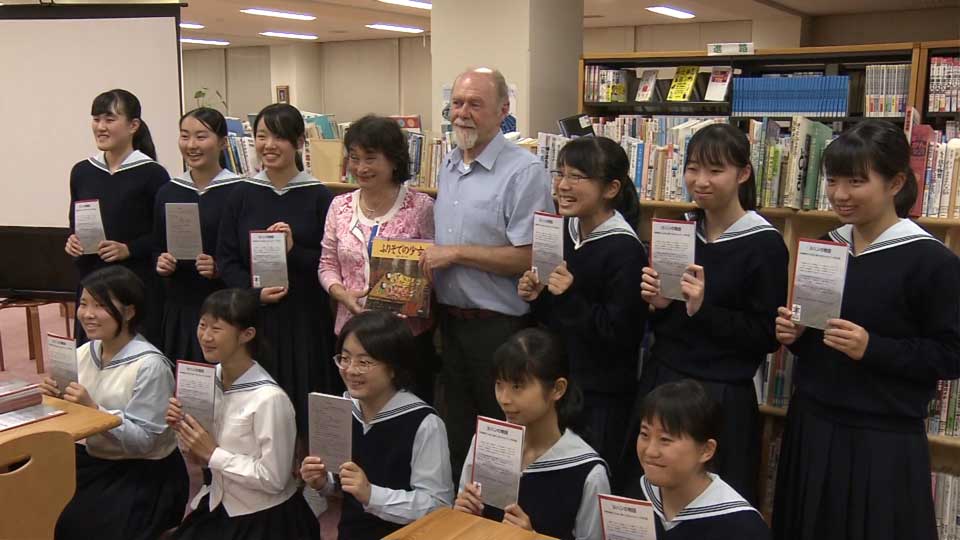

A Dutch NGO that advocates dialogue to foster war reconciliation sent 71-year-old André Schram to speak at a Japanese high school. Schram used to be a professor of biology at the University of Amsterdam. When he retired about 10 years ago, he began researching his father’s wartime experiences.

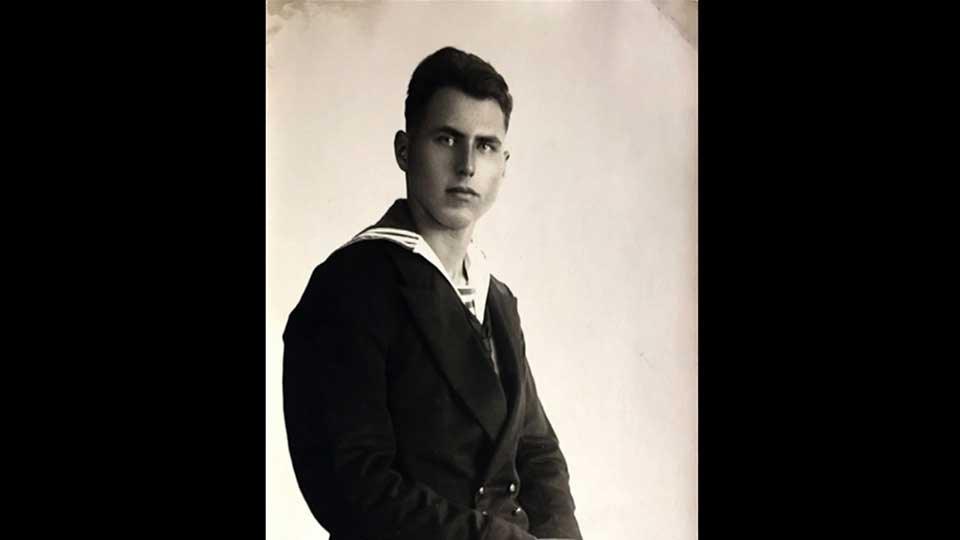

In 1942, his father Johan became a prisoner of the Imperial Japanese Army in the Dutch East Indies, now Indonesia. He was held in a camp in Nagasaki called Fukuoka 2.

André says conditions were harsh in the camp, and the guards violent. Prisoners were sent to work at a shipyard with little food or medical care. Many of them died.

A long-held hatred

Johan survived, though, and returned to the Netherlands. But he told his son nothing of his wartime experiences until just before he died at the age of 75. André learned then about his father's hatred of Japan.

André recalls his father saying "I will never kneel down for the Japs. I won't bow for them."

But he could never ask his father the details of his experience, and it left him with a deep distrust of Japan that he carried with him for decades.

Nagasaki visit prompts a rethink

When Johan died, André wanted to learn more about where his father had been held, so in 2009 he traveled to Nagasaki. He says that visit helped him overcome the negative feelings his father had left him.

In 2015, an event in Nagasaki added more nuance to André's view. People there paid for a stone memorial for prisoners of war and their families, and they erected it at the site of the camp.

The effort was led by atomic bomb survivor Toyokazu Ihara. Shortly before his death in July 2019, he explained his motivation.

"I can’t talk about my own suffering without talking about Japan’s history of aggression toward other countries. I’ve been giving talks overseas about the devastation caused by the atomic bomb. But people don’t respond unless I speak about the broader context."

The inscription on the memorial ends with the following message:

"In memory of those who lived in such harsh circumstances, to which some of them succumbed, and with a profound sense of remorse, we proclaim our fervent hopes for everlasting peace in the world."

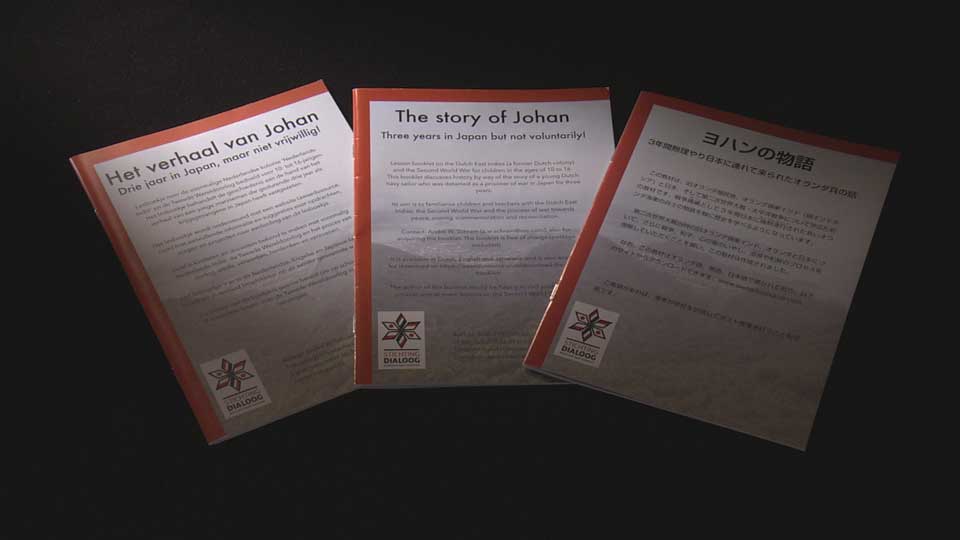

It was one of the factors that prompted André to write about how the war had damaged both Japan and the Netherlands. The resulting booklet, called The Story of Johan, took three years to write. It begins in the East Indies, current day Indonesia, back when it was a Dutch colony. Johan was one of the troops stationed there in the 1940s. When Japanese forces arrived to occupy the country, he was taken as a prisoner of war and sent to Japan.

He was imprisoned in a district of Nagasaki called Koyagi. André says it was an area so poor that even the local people went hungry. They too were victims of the war, he says.

André has a nuanced take on the bomb. He disputes the prevailing view in the west that Japanese people were universally guilty parties in the war. "Many were victims themselves!" he writes.

A new perspective for peace campaigners

Last year André visited Nagasaki for a fourth time. He interviewed people who lived near the POW camp at the time, as well as survivors of the bomb. He wanted to meet as many as possible before they are all gone.

He also sat with members of a high school peace study club. The students interview atomic bomb survivors and campaign for an end to nuclear weapons. But it was the first they had heard about Japan's conflict with the Netherlands. For most of them, it was also the first time to hear about the prisoners of war.

One of the students asked André what he thought of the bomb, and the fact that the US government may have known there were prisoners of war in the city. André said he had mixed feelings about it.

"It's difficult," said André. He explained that his father was released after the bomb was dropped, so it is possible he would never have been born without that event. Nevertheless, his real view of atomic bombs is "No. Never."

André told the students he shares their view that communication can lead to true reconciliation. He is now working to expand his booklet with new material on the war, and on post-war experiences in the Netherlands, Indonesia and Japan.