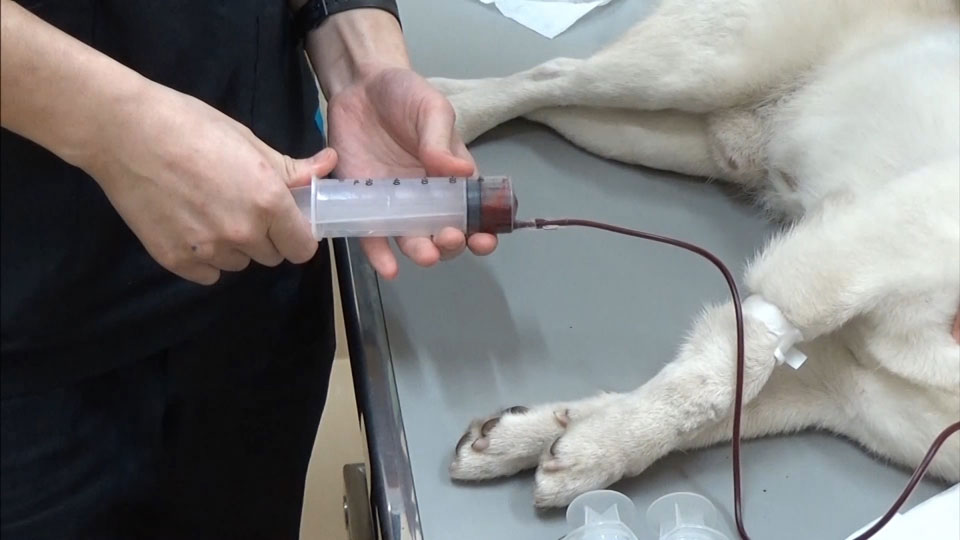

Cases like Jennifer's are common in Japan. The country has no system in place to provide animal hospitals with blood, which is the norm in the US and Europe. This is because the government says it can't ensure the safety of blood sharing programs. So clinics are instead forced to secure their own supplies.

The problem is being exacerbated by a recent rise in the number of transfusions across the country. Tendo Animal Hospital in Tendo City, Yamagata Prefecture, performs more than 600 transfusions every year. This number has risen about 20 percent over the past ten years.

Tendo asks owners if they are willing to put their pets on a list of possible donors. In return, it offers free checkups and immunizations. Other hospitals have similar arrangements, and some also keep their own dogs on-site for emergency situations.

Despite such measures, animal clinics tend to find blood in short supply. Tendo head Toru Kurita says there have been some cases in which his hospital was unable to save a life because it did not have enough blood.

"Our stock is low because we perform a lot of transfusions," says Kurita. "It's a regrettable situation."

Experts say vets have found this surge in transfusions even more difficult to handle because of the rising popularity of small dogs. Breeds such as Chihuahuas and toy poodles are increasingly common pets in Japan. But they pose a problem for animal clinics as they are too small and do not have enough blood to serve as donors. This has weakened an already shallow donor pool.

Furthermore, vets also have to grapple with the large number of dog blood types. It is believed there are at least 13 blood types and while transfusions between different types is possible, compatibility differs by case.

However, there is hope that a chemical alternative could improve the situation. Professor Teruyuki Komatsu at Chuo University's Department of Applied Chemistry has developed artificial blood for dogs and cats, which he says can be given to all pets, regardless of blood type. It still needs government approval but Komatsu says his goal is for the blood to be in use within ten years.

The Japan Pet Food Association says there were about 9 million dogs and 10 million cats kept in Japan as of last October. With average lifespans of about 15 years, these pets are long-term family members. For owners, there is an urgent need for a system that offers better care and protection of their loved ones.