On the run

The disappearance of foreign workers has long been a challenge for Japan. But the problem has grown more acute in recent years. The Immigration Services Agency says 9,052 foreign trainees went missing in 2018, nearly double the figure from 2014.

Every single one of them arrived in the country as part of the state-sponsored Technical Intern Training Program. The idea behind the policy, introduced in 1993, was to bring in labor from developing countries and send the workers home three years later, equipped with valuable technical skills.

As of June of last year, more than 367,000 laborers are in Japan as part of the program. They are active in a variety of industries, including construction, manufacturing, and food production.

For the trainees, the program is not only a chance to immediately earn several times what they could back home. It also offers them hope for a future filled with opportunity, thanks to the skills they acquire during their time in the country.

Dreamland turned to limbo

But the number of trainees who have disappeared tells a different story. NHK was able to track down and talk to a few of them. They say the reality at their workplaces was very different from what they had expected.

Three young men from a southeast Asian country who asked not to be identified, fearing harassment back home, were sent to a farm in Nagano Prefecture in 2018 as part of the program. They had signed up after hearing they could save thousands of dollars by working in Japan.

But it took only a few days on the farm for them to realize they would collapse from exhaustion before achieving their dream. They told NHK they were forced to work from 2 a.m. to 5 p.m. while in season, and their overtime pay was well below what they had been told.

After six months of these conditions, the three could take no more. They decided to run away.

Despite only speaking Japanese at a beginner level, they relied on a network of foreign workers to travel from the farm to Kyoto where they found new work.

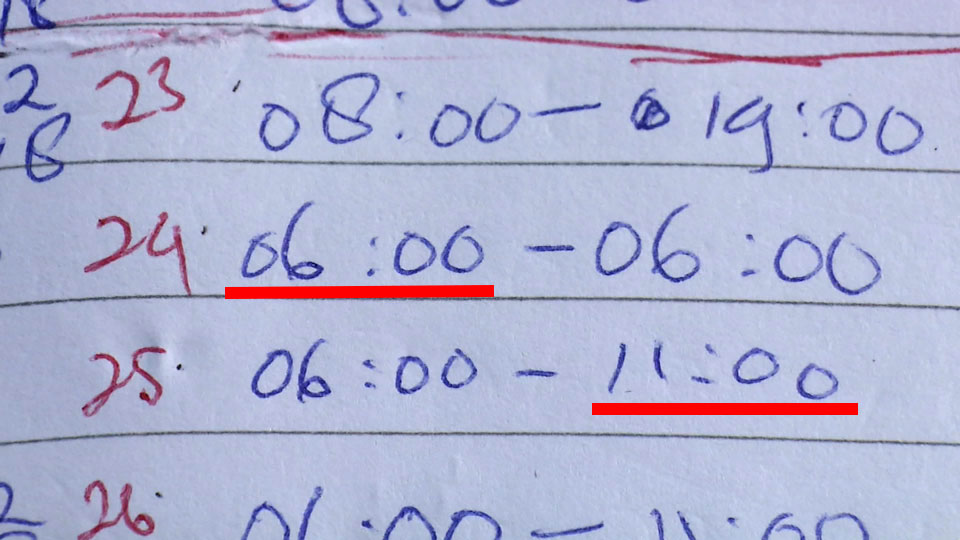

But things only got worse. They were hired by a small construction company and were forced to work from 6 a.m. until 11 a.m. the next day. They say they received almost no payment for their labor.

Rampant exploitation

Stories like this one have seen the Japanese government come under heavy fire, both from within the country and abroad. Last March, in the face of a growing chorus of critics, the Justice Ministry put out a survey of more than 4,000 organizations involved in the trainee program. It found that more than 750 people had fled their workplaces after suffering from a range of abuses, including underpay and overwork.

In November, the Immigration Agency said it would be tightening measures on businesses and supervisory organizations. It also said companies from which many trainees had fled would be suspended from the program, and banned altogether if they were found to have engaged in illegal practices. The Agency also said it was considering making the names of these companies public.

But according to Yoshihisa Saito, associate professor at Kobe University's Graduate School of International Cooperation Studies, these measures will not solve the problem. Saito has tracked the working and living conditions of Vietnamese trainees for many years.

Saito dismisses these measures as a band-aid, a hasty solution applied after the mass disappearances had already taken place. He says the more pressing need is to make sure the trainees are given a healthy and comfortable working environment to start with. Saito says the government can do this by putting in place stricter checks and tighter supervisory standards, along with a more thorough revision of the overall trainee system.

He also says there needs to be a support system for the workers who have already fled, such as properly functioning shelters.

Saito says one of the biggest flaws of the current system is that foreign trainees are only allowed to work in the business category they are initially contracted to. This makes it hard for them to find alternative work. It forces them to confront a Hobson's choice: stay and suffer, or flee and take your chances with illegal work.

Japan recently revised its immigration law with a view to accepting even more foreign workers. But this measure seems to have been passed without full consideration of the rights and living conditions of the workers.

International criticism of Japan's human rights record with regard to foreign workers is growing. Mariko Yamaoka, Director of Not for Sale Japan, a human rights watchdog group, says Japan could be labeled a modern slave state.

If Japan is to shed this troubling reputation, it will have to improve conditions for foreign trainees--and quickly--while also tackling the issues at the root of the increasing number of disappearances.