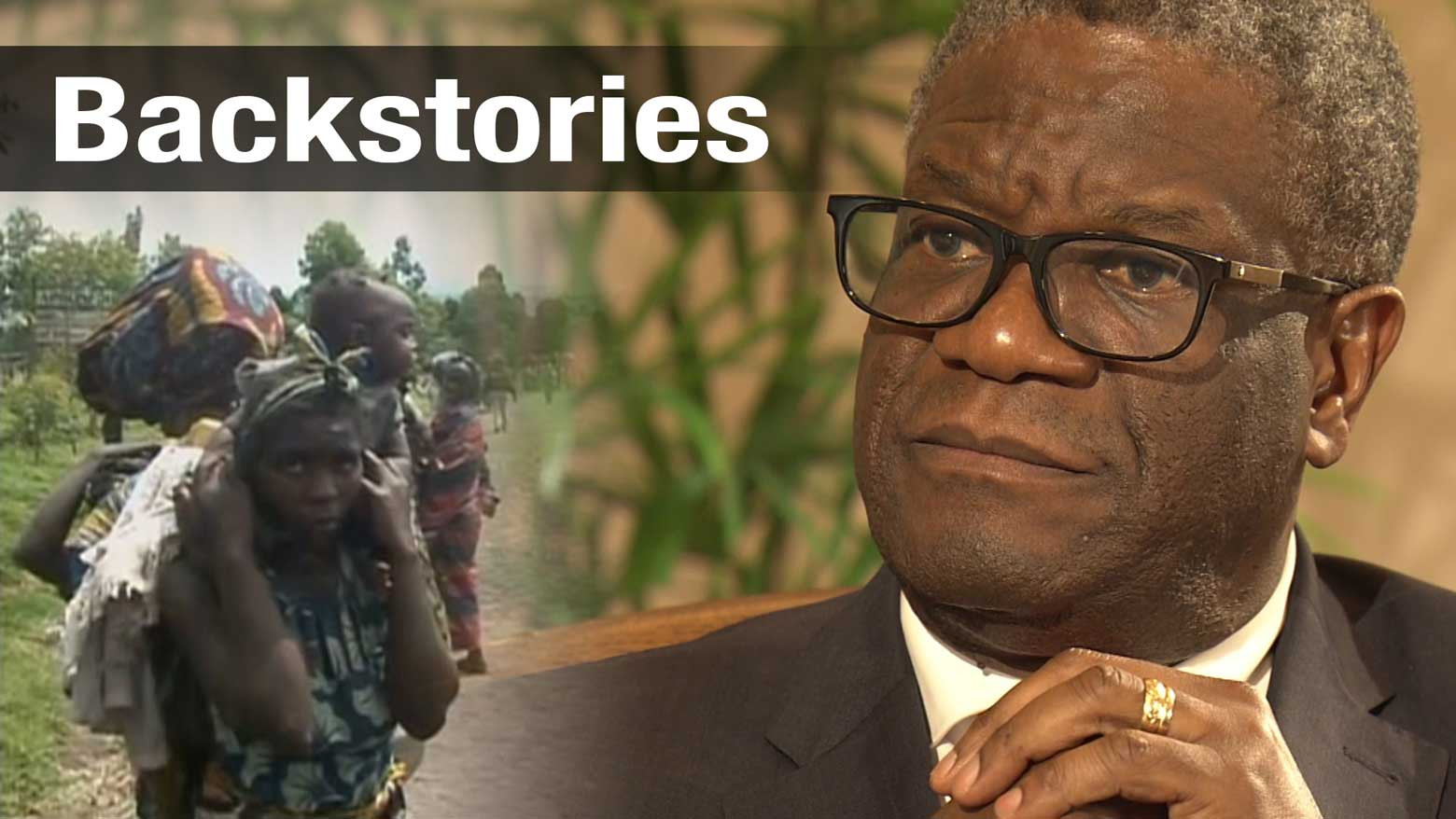

One year later, his struggle goes on. His country is still gripped by conflict and women continue to be targets of the violence.

Caring for the victims of sexual violence

Mukwege is the director of Panzi Hospital in eastern Congo. For over 20 years, he has cared for more than 55,000 victims of sexual violence, ranging in age from 6 months to 80 years old. For these women, the impact-- physical and psychological--lasts a lifetime.

This is why Mukwege does more than just administer medical treatment. He says he has a holistic approach, providing psychological and social care as well.

The meaning of reparation

But is it really possible for people who have gone through such horrific experiences to fully recover? And if their lives are changed forever, is reparation possible? Mukwege says the work he does at the hospital is just a small part of the healing process and the rest depends on the victims themselves. He says recovery is only possible when women feel they have regained their dignity and feel strong enough to re-enter society. And this is never easy.

In many communities, there is a stigma attached to rape. Survivors are often ostracized and, in some cases, even disowned. Sexual violence can tear apart a society and cause lasting damage.

The doctor's visit to Hiroshima

This October, Mukwege was in Japan as part of a global speaking tour. He stopped in Hiroshima, eager to find out how the city was able to rise from the ashes following the atomic bombing at the end of World War II. He wanted to learn how the survivors found the courage to live on with their pain and agony.

Mukwege says Hiroshima's resilience following the atomic bomb is testimony to the perseverance of the human spirit. He says he wants to see the same in his country.

Condemning the culture of impunity

Mukwege has criticized the Congolese government for not doing enough to halt the violence against women.

In 2010, the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights published a 550-page report on the most serious violations of human rights and international humanitarian law committed in the Congo. However, no action has been taken since. Mukwege says the lack of action and a prevailing culture of impunity have shielded those responsible.

A smartphone means a small piece of Congo in your pocket

I asked Mukwege who benefits from the cycle of violence. He answered the militias that get wealthy off the rare mineral coltan.

Whenever there is conflict between armed groups over the country's coltan-rich areas, sexual violence follows. The mineral is in high demand because it is crucial to the production of electronic devices, such as smartphones.

Mukwege was quick to add that those of us with smartphones in our pockets play just as big a role in this cycle of violence as those who transport the minerals across borders. "A smartphone in your pocket means a small piece of Congo in your pocket." And he says Japan is no exception. Smartphone demand--from every corner of the globe--is fueling the violence.