Disaster prone transmission lines

At one point in September, more than 930,000 homes in Chiba Prefecture were without electricity. Typhoon winds uprooted trees and knocked over utility pylons, severing their cables. Faxai was estimated to have damaged or destroyed about 2,000 utility poles, mainly in the prefecture.

Transmission lines are also vulnerable to earthquakes and tornados. The huge quake and tsunami that struck eastern Japan on March 11, 2011 damaged 56,000 utility poles.

Time to bury the cables

Inspecting the damage in Chiba, Infrastructure Minister Kazuyoshi Akaba said it reinforced his belief that power cables should be moved underground. He said he would work harder to put that in motion.

Putting the cables underground is part of a comprehensive plan to prevent power outages during inclement weather, with the added benefit of fewer obstacles on roads and a better view of the skies.

Japan lags behind other countries

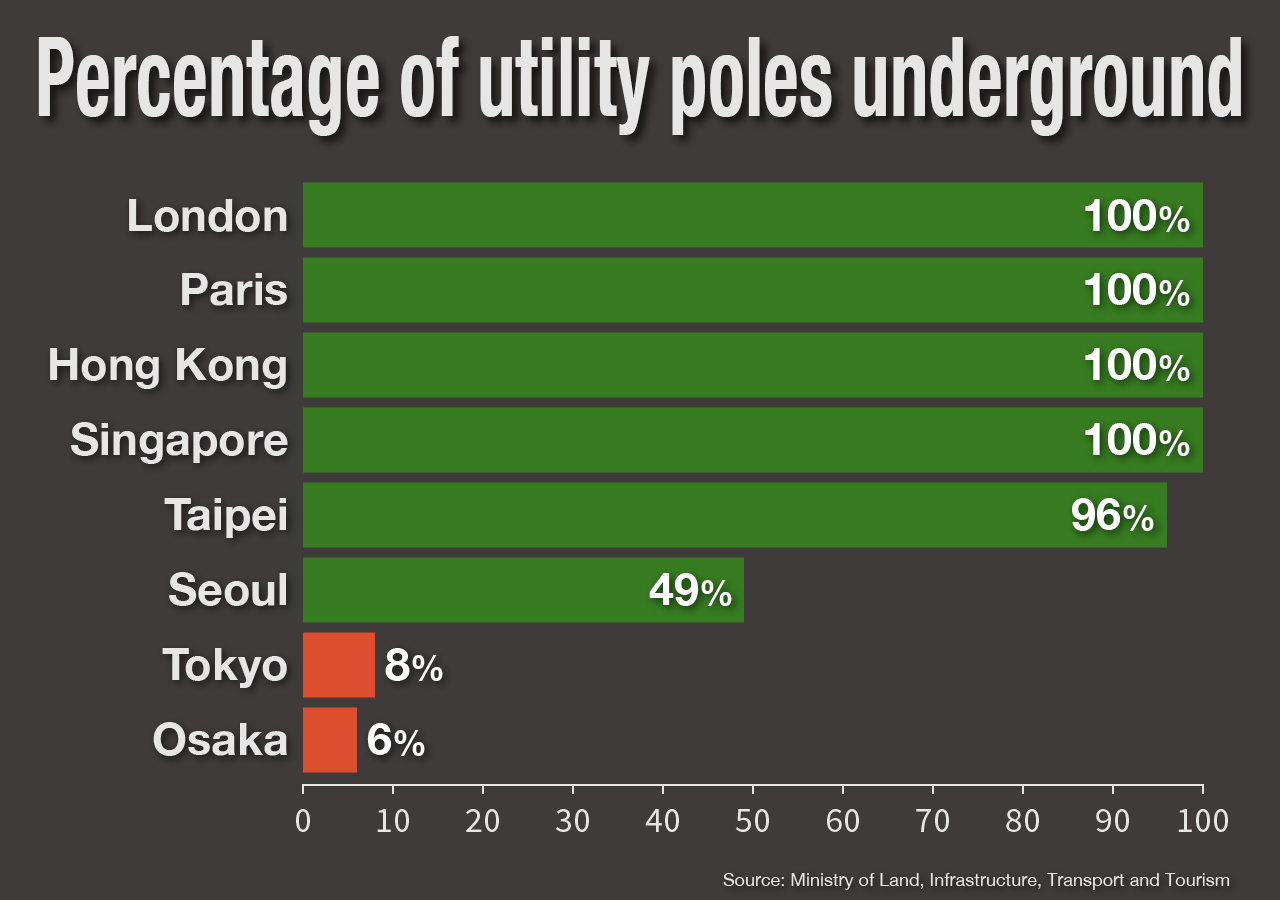

In contrast to urban areas in Japan, major cities like London, Paris, Hong Kong and Singapore have no utility poles, relying on networks of cables that are completely underground.

In a country prone to natural disasters, Tokyo is taking the lead in this effort, but an infrastructure ministry survey shows only 8 percent of roads in the capital have been cleared of utility poles, and less than one percent of roads in about 40 percent of Japan's prefectures are currently pole free.

On the contrary, the number of utility poles in the country increased, from 35.25 million in 2008 to 35.85 million in 2017.

Legacy of rapid postwar reconstruction

An official with the infrastructure ministry called this a negative outcome of the country's effort to rebuild after World War Two.

The official said there was a push before the war to lay power cables underground, but the government's priority after the war was to provide a quick and stable supply of electricity, and erecting utility poles was faster and cheaper. The official said this view remains common to this day.

The government passed a law to rid the landscape of utility pylons three years ago. The plan was to clear 2,400 kilometers of roadway by March 2021.

However, analysts say achieving this will be difficult as the government has yet to secure funding for the project. The cost of removing pylons and placing cables underground for a 1-kilometer section of road is estimated at 530 million yen, or about 4.9 million dollars.

The dilemma of moving underground

Some of the reasons for the high cost are unique to major Japanese cities like Tokyo, where space is limited, even underground.

An NHK crew visited the construction site of a new Tokyo metro station. The team saw conduits large and small crisscrossing in the dark underground passageways. They included gas and water pipes and power and communication cables for the construction work.

Experts say Tokyo's underground is the most complex in the world, and this subterranean web is a major obstacle to clearing the surface roads of poles. If power cables go underground, they need to pass through this already-overcrowded maze.

But the experts say there is no comprehensive blueprint of all the underground conduits. The gas pipes are managed by the gas companies, the water pipes by the municipalities, and the power cables by electric firms. Moving utility cables underground would require workers to sort through all of these blueprints to find space.

A construction official at the metro site pointed out that problems often arise as conduit locations differ from the blueprints. This could result in accidents causing damage to existing cables.

These are just some of the reasons for the lack of progress in relocating utility cables underground. But the massive blackout in Chiba Prefecture and the effects of other natural disasters on people's daily lives suggest it is high time Japan got moving on the project.