It’s difficult to analyze the current status of the global economy, especially the US. The jobless rate there is still at a historically low level, and the stock markets are holding steady. But the August ISM manufacturing purchasing managers’ index fell to the lowest reading in three years. Exports have been weak amid US-China trade tensions, and wage rises have been slow.

In other words, we’re seeing symptoms of a cold, but we’re not entirely sure if this will develop into a severe illness.

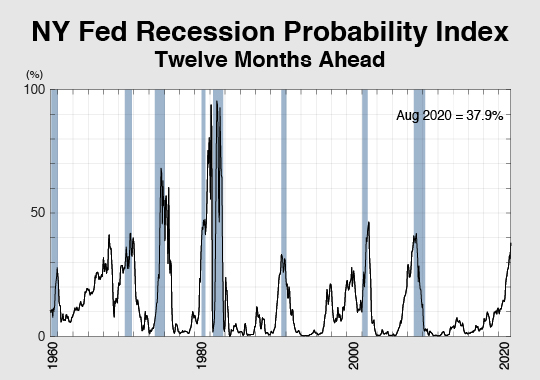

Fed Chair Powell explained in his press conference that the latest rate cut is meant to “provide insurance against ongoing risks.” While market players also welcomed Powell’s vow that the Fed will act further if necessary to sustain the country’s economic expansion, other policymakers and economists at the Fed are more reluctant. Some feel that the NY Fed indicator is no longer a reliable recession predictor, since the numbers are derived from the gap between short and long-term interest rates. The long-term interest rates have been unusually subdued due to prolonged monetary easing.

Many policymakers, including Powell, feel that the political downside risks are also a big factor in raising the chance of a recession. Powell says the “trade policy is weighing on investment decisions.” It’s no secret that President Trump’s trade row with China is one of the major factors that’s dragging down the economy.

In Europe, “Super Mario” -- the respected European Central Bank President Mario Draghi -- once again played a leading role in putting together a bigger-than-expected monetary easing package. The ECB decided to lower the deposit rate from minus 0.4 percent to minus 0.5 percent, and resume quantitative easing by reviving bond purchases. Many governors of the ECB have been voicing opposition to making an aggressive leap, but Draghi was firm. Germany is recording negative growth due to slower exports to China. Risks loom as Eurozone’s production is decreasing and Brexit is looming.

Market players seem to be somewhat relieved by the recent moves made by the US Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank. But experts warn that it may be too soon to sit back and relax.

Reason number one: it’s unclear whether the Fed and the ECB can continue on with their course of easing with little ammunition left. The Fed’s federal funds rate is in the range of 1.75 percent to 2 percent. The ECB is already on a path of negative interest rates. That means that both institutions don’t have that much room for preemptive measures, with worries that they will be empty-handed by the time a real financial crisis actually hits. The latest release from the Fed shows that 10 out of 17 participants at the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) think no further rate cuts are needed.

Another reason to be concerned is the ballooning debt. It’s estimated that debt levels have risen by 50 percent of what they were a decade ago, just before the global financial crisis. With more easing from the Fed and the ECB, the risk may grow further.

Leveraged loans have already exceeded a trillion dollars, and analysts warn that a large portion of them are now held by Asian banks, including Japan, in various forms of repackaged financial products. European banks suffered a decade ago after they bought securities backed by US subprime mortgage loans.

That also brings us to the question of how the Bank of Japan will act next. The BOJ decided to leave its negative interest rate policy unchanged in September. But the economy faces headwinds. Japan faces a consumption tax hike in October. Exports and business investment are slowing due to the US-China trade friction. And with the Fed and ECB cutting key interest rates, the Japanese yen may rise even further against the dollar and the euro.

BOJ Governor Haruhiko Kuroda told reporters that he is now “more inclined to go ahead with easing compared to the previous July meeting,” and that the “BOJ has the capacity to ease further.” The Bank will hold its next meeting at the end of October and “reexamine” economic and price developments.

Prospects are unclear due to geopolitical risks that aren’t going away anytime soon. Global trade rows and protectionist moves can further dampen global economic growth. US-Iran tensions could develop into an oil shock or push up crude prices. And protests in Hong Kong are fueling the US-China friction.

The lesson learned from the global financial crisis a decade ago was that central banks need to act swiftly and decisively in times of trouble. But few would have imagined that the unprecedented monetary easing would go on for more than ten years.

Central bankers will need to navigate carefully as if they are moving forward on thin ice. Now that we know that monetary easing is no magic wand, we should start exploring other ways to boost economic growth.