In August, Immigration and Customs Enforcement Officers arrested nearly 700 undocumented immigrants in Mississippi. And as Trump continues to ramp up rhetoric on deportation, many undocumented residents living in the U.S. are terrified that one day, they too will be arrested.

One person who lives with this fear is 49-year-old Sara, who asked that we don't use her real name.

"I simply live and exist day to day, just trying to survive and make sure that I don’t get picked up," she says. "I live like a fugitive. As you can see, I have to protect my identity.”

But Sara didn’t go to the U.S. illegally. Born in Iran, she was legally adopted by US citizens when she was two. Her adoptive father was a lieutenant colonel who fought during World War II and the Korean War. He was even a prisoner-of-war, defying all odds and surviving a death march in brutal temperatures while captured in Germany.

In the hope of providing Sara with a better life, he took her to the U.S. Nearly half a century later, Sara is still waiting to become a legal citizen. And she isn’t the only one.

An estimated 49,000 adoptees in the U.S. have never been granted citizenship. Many parents didn't realize that they had to naturalize their adopted children when they brought them into the country. Sara says her parents knew she had to be naturalized and hired a lawyer to take care of the process, but the documents were not filed correctly by the government.

Sara first discovered that she was an illegal immigrant when she applied for a passport 11 years ago. Since then, her life has been clouded with fear and anxiety. She fell into depression, and began suffering frequent stomach pains and insomnia.

"I never imagined part of my adoptee experience was to go to bed at night with fear and wake up with fear," she says. "I fear that my life will be taken from me."

The U.S. attempted to resolve the problem for adoptees with the Child Citizenship Act of 2000. It granted citizenship to certain foreign-born adopted children of U.S. citizens. But the law had a big loophole—children born abroad before February 27, 1983 did not qualify.

To fix this problem, the Adoptee Citizenship Act, or ACA, was tabled in 2015, and has been reintroduced every year since, but has yet to become law. It’s currently stalled in Congress.

According to Joy Alessi, program director at Adoptee Rights Campaign, part of the challenge is educating legislators that the ACA bill is an adoption bill, not an immigration bill. Alessi says the immigration portion in this case is just a very small detail.

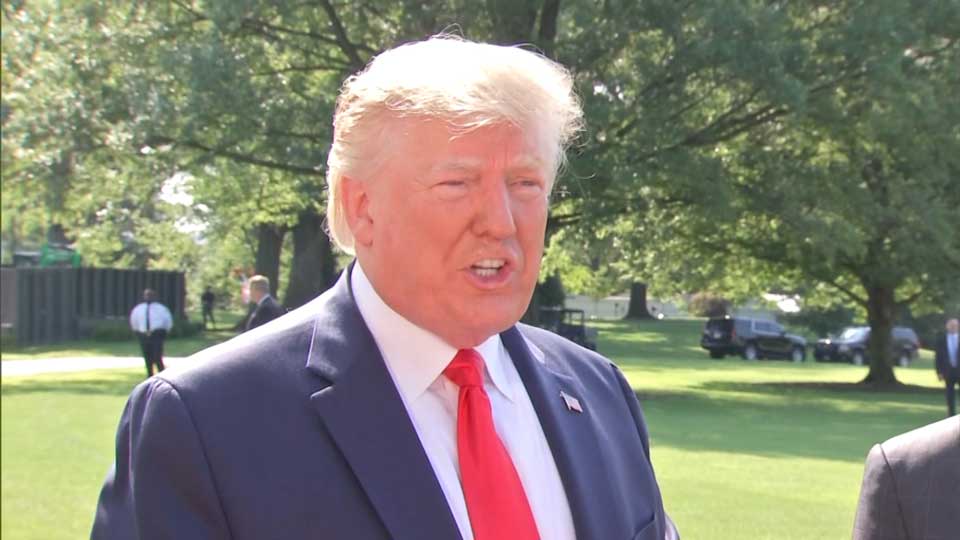

Congressman Adam Smith, one of the sponsors of the ACA, says it’s becoming more difficult to relay this message when the Trump administration wants to make it harder for most undocumented residents to get citizenship.

“The immigration controversy existed long before Donald Trump ran for president, but he has certainly stoked the fire,” says Smith. “If you came over as an adoptee and never got your citizenship, with the zero-tolerance policy, you are potentially subject to deportation given the Trump administration's approach to enforcement.”

Smith is trying to gather more co-sponsors and gain as much bipartisan support as he can.

In the meantime, there’s nothing Sara can do but wait. Without citizenship, finding a job is all but impossible. Many adoptees can’t even get a driving license. Sara was recently denied a home loan and, despite having paid taxes for years, she’s unsure whether she will receive retirement benefits.

She says she’s losing hope that the government will fix a problem it itself has caused. “I’ve been on this journey for over ten years and I’m not any closer to citizenship than when I found out ten years ago.”

Scattered on the walls of Sara’s house are decorative signs with the word ‘home’. When asked what home means to her, there’s a long pause, and tears well up in her eyes.

“I don’t have a home. I don’t belong in Iran or the United States," she says. "I want the U.S. government to start recognizing that this is my home and not to discard me, throw me away or abandon me again.”