Every year on the anniversary, people visit Urakami Cathedral, located about 500 meters from ground zero, to pay tribute to the victims, or "Hibakusha".

This year, the cathedral received some exciting news. A long-missing cross that had adorned its interior before the bombing had survived, and had been in the US for all these years.

On August 7, two days before the anniversary, the cathedral held a ceremony for the returning cross. And on the anniversary, it was brought in for evening mass.

History of the cross

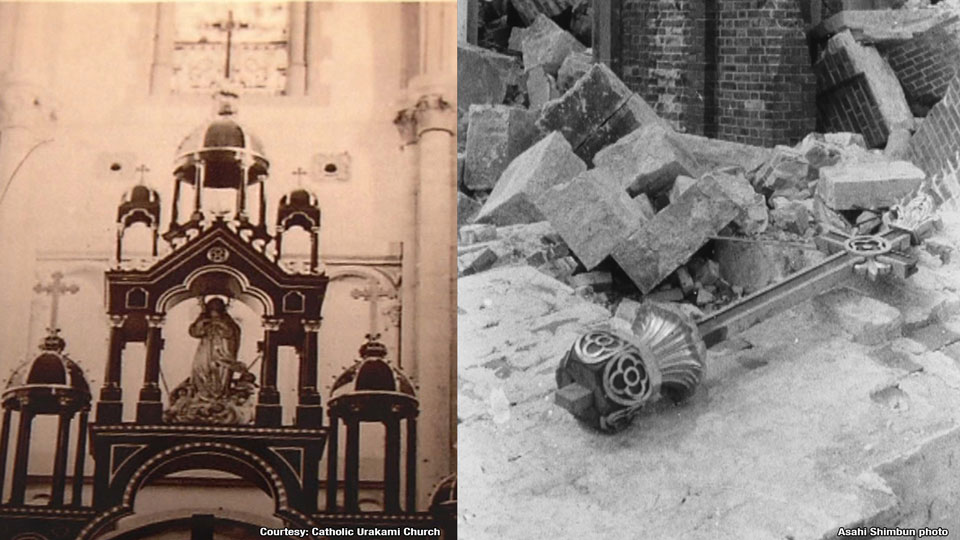

Before the bombing, the cross held a place of prominence in the cathedral, at the top of the altar.

In an image taken about a month after the bombing, the cross was seen lying in the rubble of the cathedral. Shortly after this, it went missing.

But in May this year, the Archbishop of Nagasaki received a letter from a college in the United States. It said the school was in possession of the cross, and wanted to return it to Urakami Cathedral.

A closer look

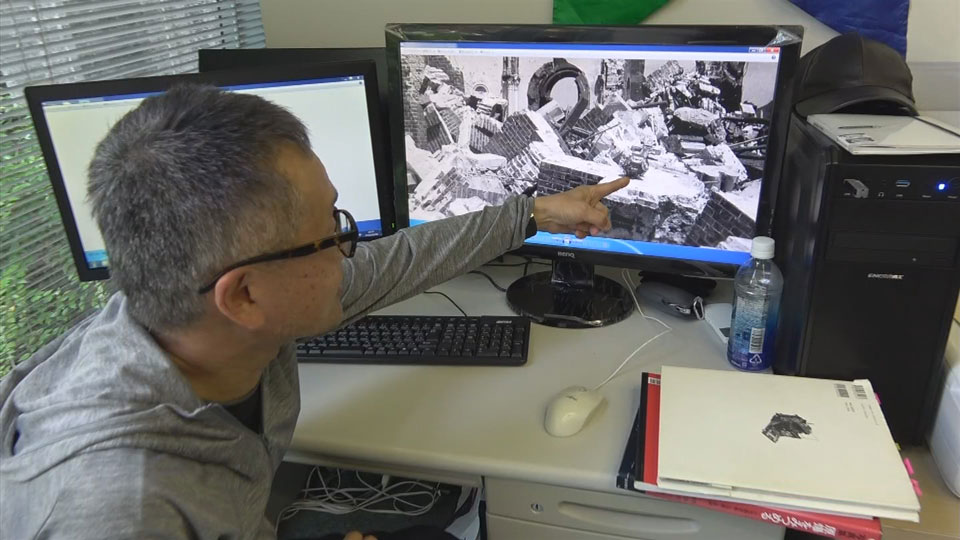

After receiving the letter, a group was brought in to make sure this was the same cross that hung in the cathedral before the bombing. The Committee for Research on Photographs and Materials Related to the Atomic Bombing works under the Nagasaki Foundation for the Promotion of Peace.

The committee compared the cross in the picture sent by the college with old photographs.

In the picture sent by the US college, the wooden cross has a distinctive flower-shaped design in the middle with gold edges, and stands about a meter tall.

To compare it with the old cross, the committee looked at pictures of it lying in the debris and, examining bricks from the rubble, calculated that it was also about one meter tall.

There was also a similar flower pattern and scratches in the same places.

One of the founders of the committee is 90 year-old Yoshitoshi Fukahori. He is a "hibakusha" and a devout Catholic. He has spent about thirty years searching for the cross.

When Fukahori saw the photo of the cross sent by the US college, he was sure it was the same one from the cathedral altar.

“I was very surprised by the discovery," he says. "It explains why we couldn’t track down the cross. It was in the US all along. But I’m so glad to find out that it survived all these years.”

Given to a US marine corps officer

In the letter to the archbishop, the college said the cross was brought to the United States by someone named Walter G. Hooke.

NHK tracked down a relative of Hooke's living in the US, a niece named Megan Rice. She is 89 years old and is a Catholic nun. She told us about her uncle's life during and after World War Two.

Hooke was a Marine volunteer during the war. Afterward, he served in Nagasaki as part of occupation forces. Rice says her uncle seldom spoke to his family about his time in Japan. She says he struggled for a long time with trauma from the war.

"I think he really had PTSD," she says. "I mean he was obviously struggling with that trauma of what he had seen."

Walter was a devout Catholic and during his five months in Nagasaki, he became friends with a local bishop, Aijiro Yamaguchi. The two found they shared a grief over the suffering of Nagasaki.

Yamaguchi eventually decided to give Walter the cross. After he returned to the US, Walter hung it in his dining room.

Hooke's anti-nuclear activities

Walter’s life changed after he retired from his job at a shipping company in the late 1970s. He began learning about fellow servicemen in Nagasaki who had developed cancer. For eight years, he lobbied the government until a law was passed to compensate veterans exposed to radiation.

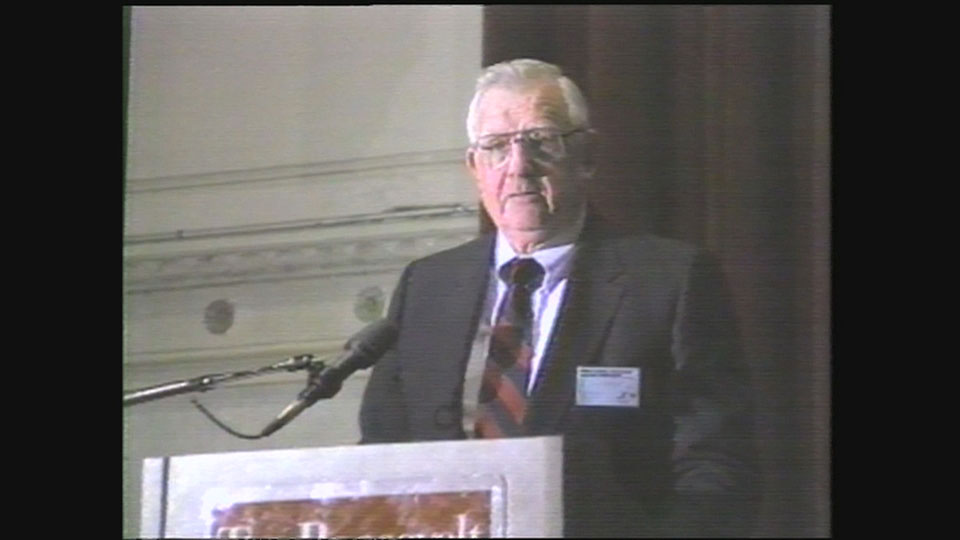

He also became involved in the campaign to abolish nuclear weapons. In 1987, he spoke at a conference in New York of A-bomb survivors and victims of nuclear tests from twenty countries.

Walter devoted the remaining years of his life to nuclear disarmament. He died in 2010 at the age of 97.

In an interview he gave a few years before his death, he said, "I can't see anybody that, if you ever really realize what happened in Nagasaki and Hiroshima, would ever possibly consider using them again."

Passing down Hooke's anti-nuclear sentiment

Megan was inspired by her uncle's life. She became involved in the anti-nuclear campaign, joining demonstrations, lobbying Congress, and circulating petitions.

"He inspired me by his willingness and his drive to pursue a goal," she says. "The cross represents in my view many things. But it represents people dying because of their convictions."

In 1982, Walter decided it was time for the cross to leave his dining room. He thought of the Peace Resource Center at Wilmington College in Ohio, which had a strong record of anti-nuclear activism.

Tanya Maus is the center's current director. She often speaks to visitors about Walter's convictions and his relationship with the cross.

"I think ultimately he came to decide that the use of atomic weapons in Hiroshima and Nagasaki was unjustified."

It was Maus who decided that, even though it was an important part of the Center, the cross needed to be returned to Nagasaki.

"To me it represents the center very strongly but the larger sense of giving back outweighs the need for the cross to be here," she says. "As an artifact and as a sacred object, I think its home is in the Urakami Cathedral."

In July, the day came for the center to say goodbye to the cross. The people of Wilmington gathered to pray and show their gratitude. In its departure, the cross left the town with the conviction of Walter's anti-nuclear beliefs.

The cross is back in Nagasaki. Along with the victims, survivors and advocates, it is now part of Nagasaki’s legacy of how a city can be torn apart by war. But is also a symbol of hope for a world without nuclear weapons.