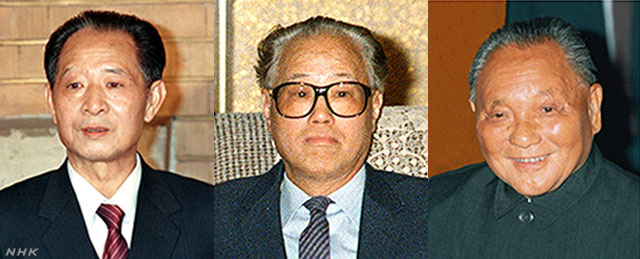

Bao Tong was a secretary for the late Zhao Ziyang, the Communist Party General Secretary at the time of the protests. Zhao was a reformist whose sympathetic views of the students meant he was purged from the party following the crackdown.

Reformists versus conservatives

At the start of the 1980s, most of China lived in utter poverty. The monthly salary of a doctor was barely enough to buy a single roll of color film. Most people thought it was time for the country to shift toward democracy, calling for a political system like those seen in Japan and the United States.

That decade, the Communist Party selected two successive reformist general secretaries, Hu Yaobang and Zhao. Under their leadership, China underwent gradual economic and political reform.

However, the Party's powerful elders statesmen were uneasy about the country's slide, however moderate, toward democracy. Bao, Zhao's secretary, believes the Tiananmen crackdown was a setup orchestrated by one of these elders.

Deng Xiaoping had been the Party's supreme leader since the death of Mao Zedong. He handpicked both Hu and Zhao.

Preservation of one-party rule

Zhang Weiguo was a senior writer at a newspaper known for its pro-democracy articles. It was forced to cease publication after state censors discovered it was preparing to release an article criticizing the party's decision to dismiss Hu.

"Deng was a strategist," Zhang says. "He knew that one-party rule would be jeopardized if political reform took hold, and there were calls for freedom of speech and against corruption."

Communist Party officials continue to insist that one-party control is needed to stabilize the country's diverse social makeup. But in interviews with NHK, many people, including former party officials, gave the opposite view.

"High-ranking party officials are afraid of losing power, which is the only thing they have," says a former university lecturer who participated in the pro-democracy protests.

"Party officials want to hold on to the vast interests that are vested in their power," says a former journalist.

Bao says Deng appointed Hu and Zhao because he sought the economic benefits of reform. But at the same time, he was always wary of loosening the Party's grip on power.

"Deng was famous for saying 'Let some people get rich first'," says Bao. "But by 'some people', he meant those in power."

He adds that in today's China, more people, not just the powerful, can attain wealth. But he says to do so, they have to obey the Party.

Protecting personal authority

Bao believes Deng staged the Tiananmen crackdown to protect his own hold on power.

Following sporadic pro-democracy rallies across the country in the mid-80s, Deng sensed that things were going too far and purged Hu. But when he died, students gathered in Tiananmen Square in his honor.

"Zhao suggested the government allow the students to pay tribute to Hu," Bao says. "At this point, Deng had already decided to oust Zhao as well."

Bao thinks Deng was worried that after he died, Zhao might besmirch his legacy in a way similar to how Nikita Khrushchev of the Soviet Union had criticized his predecessor Joseph Stalin.

Bao says despite the Party's seemingly united front, the internal power balance is actually quite delicate, with top leaders constantly worried about their authority.

"The Party's Supreme Leader can't make any mistakes because then another official would pounce," he says. "It's the nature of the Party to have a cruel and brutal internal power struggle."

The setup

At a 1987 Party Congress, delegates decided that national debates should be held on serious issues, the party must always be separated from the government.

But shortly after the Congress, the Party held a general meeting of its Central Committee where it was decided that Deng would have the final word on all matters of national importance.

This made Deng the ultimate decision maker during the Tiananmen demonstrations.

Zhao proposed that the Party hold dialogue with the student demonstrators, which Bao says Deng initially approved of.

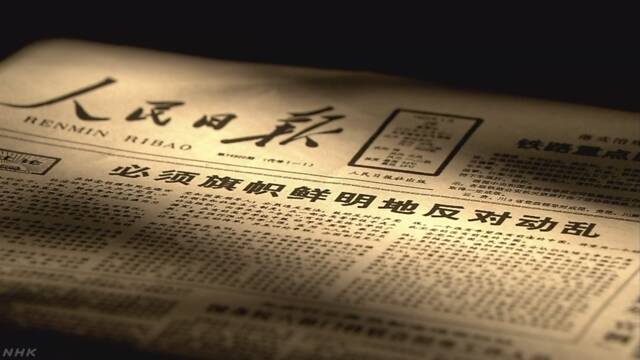

But Bao says Deng changed course and initiated his plot in 1989 while Zhao was on an overseas trip. He says Deng ordered Premier Li Peng and other conservatives to make the Party newspaper carry an editorial branding the student demonstrations as riots. The People's Daily ran the article in its April 26 issue.

"Deng felt he had to stir up a major incident which would allow him to purge Zhao," Bao says. "He feared he would face backlash from the Party if he ousted Zhao for no reason."

After a memorial event for Hu on April 22, students were back on campuses for mid-term exams. But they were infuriated by the editorial, which sparked large-scale demonstrations.

Splitting the Party

Bao says there is one chapter of the protests that is often overlooked. One million people took part in a rally on May 16, about three weeks before the crackdown.

Five members of the Politburo Standing Committee, the party's top leadership, met that day and agreed to recognize the students. The following day, the front page of the People's Daily carried a statement by Zhao praising their activities.

But there was action behind the scenes. On the next day of the demonstrations, Deng summoned Zhao to his home. They were to meet to decide on how to deal with the protestors. But when Zhao arrived, the other Politburo members were already there. They had decided to abruptly change course and impose martial law. Deng also ordered Zhao to stop the protests with the use of military force.

Later that day, Bao says Zhao asked him to write him a letter of resignation. At this point in our interview, Bao became visibly emotional, saying the Politburo's decision was unthinkable, given they had approved of the student activities just one day earlier.

Zhao was soon dismissed from his post on accusations that he split the party. He spent the rest of his life under house arrest. He died in 2005 but the Communist Party has not allowed his remains to be buried.

Bao was jailed for eight years on the grounds that he leaked classified information. He says he was accused of leaking that martial law would be enforced, something he denies.

"I was unaware of its implementation until I saw the Premier announcing it on TV on the night of May 19," he insists.

The death of reform

"Tiananmen marked the end of reform in China," Bao says. "Hu and Zhao had promoted reform for the people. But reform after Tiananmen has been for those in power."

China has experienced rapid economic growth following Tiananmen but it has not come with the increased democratic rights the students were seeking. The foundations for authoritarianism were laid during the crackdown, and China has been in its grip ever since.

"The Tiananmen crackdown was a war, not between states, but between government leaders and members of the public," Bao says. "And since then, the people have had no choice but to obey."