A change of tune

The Hong Kong authorities changed their stance just before the recent G20 summit and a meeting between the leaders of the US and China.

News of the postponement came amid speculation that US President Donald Trump would raise the issue with Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping. Protesters believe the new stance was a pragmatic move based on Beijing's wishes, rather than the leaders listening to the people.

People in Hong Kong are also protesting their inability to directly elect the head of their government.

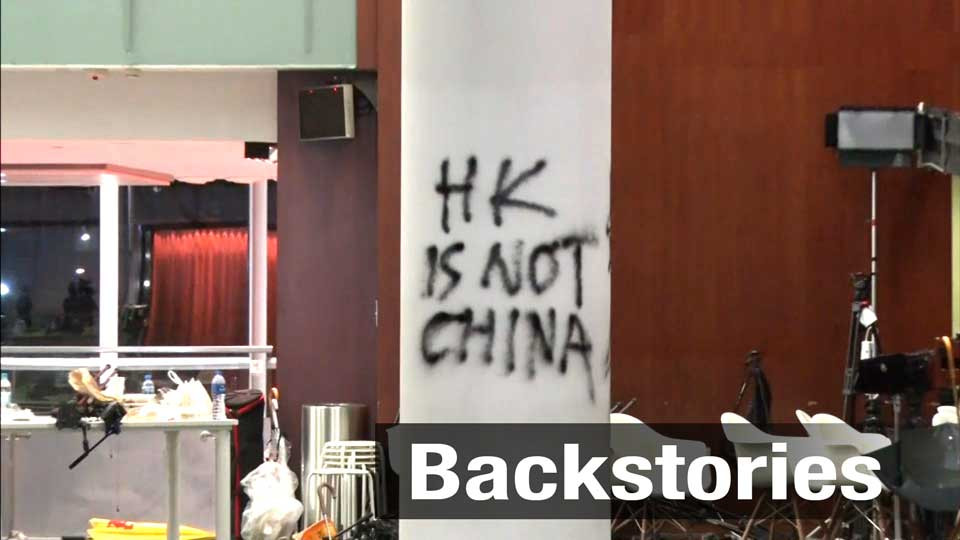

Beijing set forth its principle of "One Country, Two Systems" when Britain handed over Hong Kong to China. The principle says that Hong Kong will have a different political system from the mainland, and a higher degree of autonomy.

Hong Kong's de facto constitution says the Chief Executive will "eventually" be decided by popular vote. But 22 years since the handover, this has not happened.

Chief Executive Carrie Lam was chosen by a committee of about 1,200 people. That committee included representatives of industry associations and legislators, and about two-thirds of the members were pro-Beijing. A poll at the time showed another, more liberal candidate had far more public support.

Many people in Hong Kong harbor a strong mistrust of the legal system in mainland China.

Two years ago, the Chief Justice of China's Supreme Court told senior court judges that it was essential to block the influence of "Western countries' wrong ideas", such as the separation of powers or judicial independence.

Four years ago, five booksellers disappeared from Hong Kong and the neighboring Chinese province of Guangdong. They were selling books that criticized or embarrassed Xi and other senior Chinese officials. It later turned out that Chinese authorities had detained them. This incident fueled fears among people in Hong Kong that China's Communist Party was targeting the territory's freedom of speech.

A precedent for the protests

The pro-democracy protests 30 years ago in Beijing's Tiananmen Square occurred as China and the Soviet Union were moving towards a historical reconciliation.

Then-Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev was promoting Perestroika, or political reform, and visited Beijing for a summit with the leader of China's Communist Party. Protestors held a rally outside the summit venue, and Chinese authorities appeared to allow the protests.

Beijing appeared to be focusing on the chance to improve ties with Moscow. But as soon as Gorbachev left the country, the authorities changed their attitude and declared martial law in the capital, triggering what came to be known as the Tiananmen Square incident.

With the US-China summit talks over, Beijing may change its stance towards the Hong Kong protests in the same vein as the Tiananmen Square incident.

The crackdown reflected the fears of Communist Party leaders that the protests could put an end to the party's rule of the country. The current leadership may be seeing the protests in Hong Kong with similar trepidation. The Hong Kong rallies have received little coverage in mainland China.

The protestors are showing no signs of backing down, but precedent suggests the recent conciliatory notes from the leadership shouldn't be read as concessions.