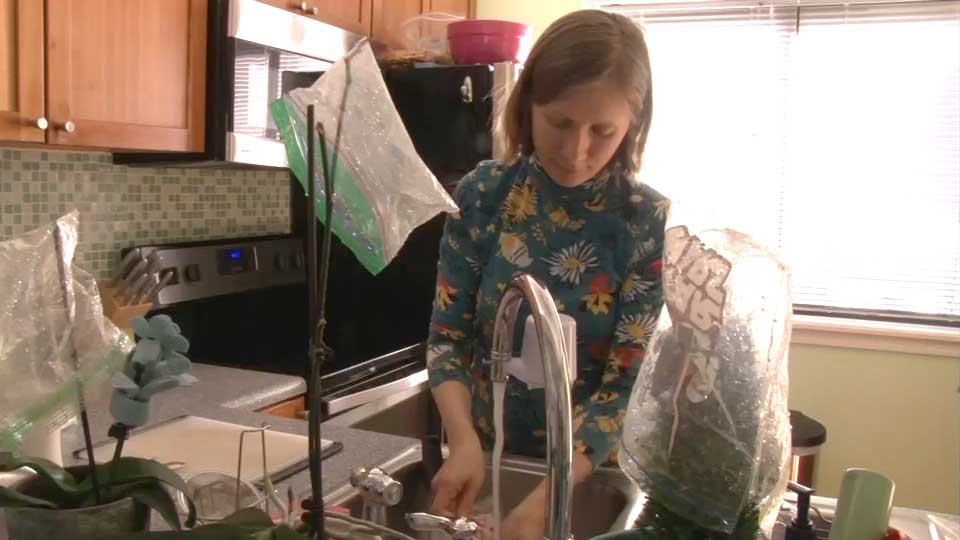

On the other side of the country, in Staunton, Virginia, Maya Kartseva washes her used plastic ziplock bags and stores them underneath the sink. On occasion, she and her family will make the two-hour drive to Washington D.C. to recycle the plastic she cannot reuse. Staunton, like the rest of Virginia's Shenandoah Valley, no longer collects or recycles plastic, leaving Kartseva no choice but to find her own solution if she wants to recycle.

From California to Virginia, municipalities and their residents are adapting to the significant shift in the global market for recycled plastic, a shift that started with a diktat from Beijing that effectively banned all plastic waste from being exported to China, starting in 2018.

"The Chinese ban has had an impact," says Jack Macy, Senior Zero Waste Coordinator with the City of San Francisco. "It's made it more expensive to recycle and we get less revenue, and we've had to find other markets."

New reality

According to the Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries, US exports to China decreased a whopping 94 percent from 2016 to 2018, while exports to Thailand and Malaysia increased by 81 percent and 300 percent respectively. As a whole, plastic waste exports dropped 45 percent during the same period; from 1.9 million metric tons in 2016 to just over 1 million metric tons in 2018. In brief, with the Chinese market out of the picture and in conjunction with the low cost of producing new plastic, it costs municipalities more to recycle plastic than it does to take it to the landfill.

In April 2019, the cities of Staunton, Waynesboro and Harrisonburg in Western Virginia came to that conclusion after their recycling vendor announced that they would no longer accept mixed plastic and glass.

"Since we don't have a vendor, we won't collect those," says Thomas Hartman, Director of Public Works for the city of Harrisonburg. "It's not an environmentally friendly answer but it's the best one that we have right now. We're just trying to be upfront and honest with our citizens to let them know that if we could, we would."

"The recycling industry is failing," says Staunton, Virginia City Manager Steve Owen in a press release announcing the cessation of plastic recycling in his city. "We're now in the unfortunate position of having to make substantial and undesirable changes to our recycling program."

Awareness the key

In Staunton, awareness of the recycling situation has been growing by the month. In January, only nine people attended an environmental-cum-recycling event held at a local coffee shop, but by late April the city's public library was hosting similar events in which upwards of 100 people from youth to seniors heard from environmental experts, passed petitions, and expressed both hope and dismay. This awareness led Kartseva to actively tackle the problem.

"We are definitely in a time of crisis right now," she says. "It's so horrible to put your plastic in the trash because you know that it will never disintegrate."

Unlike the cities of Staunton and Harrisonburg, San Francisco, because of its resources and its reputation of being the most environmentally progressive city in the most environmentally progressive state, has no choice -- it must recycle.

"San Francisco has been dealing with plastic for a long time," says Macy, in reference to San Francisco’s first in the nation plastic bag ban in 2007. "We have a strong commitment toward sustainability."

Zero Waste city

It's true. Since 2003, when the city declared its commitment to become a "Zero Waste" city by 2020, an assortment of ordinances have been passed that have helped it achieve the highest recovery rate of any city in the United States.

In addition, the city's hand-in-glove relationship with its only collector of discarded material, Recology, allows it to coordinate policy more efficiently, while giving it the flexibility to adjust to changes in the marketplace faster than most cities.

At Recology's Recycle Central, an 18,580-square-meter facility in the city's Pier 96, the company has invested $14 million in the last three years on optical sorters and other modern recycling equipment for the more than 700 tons of comingled recycling it receives every day.

"We've invested in all of these modern recycling machines, so all that together means that these bales have a very small percentage of impurities," says Recology spokesperson Robert Reed.

"These are the highest quality bales of recycled material produced in America, so in a buyer's market, buyers are more choosy and they choose higher quality. San Francisco is always able to move its recycling because we have high-quality bales."

Refusing plastic altogether

But despite the investment and the ordinances, some plastic still ends up in the landfill, so San Francisco is encouraging its residents to REFUSE to use plastic all together.

"Sending plastic to another country is not the real answer. The real answer is reducing the amount of plastic that we consume," says Reed. "Consumers have a very powerful voice in this discussion and the best way to reduce plastic is to speak with your consumer dollars. Send a message to all these companies."

That message came across loud and clear to Utting and her family, who shop with their own bags, don't buy plastic water bottles, buy in bulk and are model recyclers.

"I'm just hearing this message of refuse and I think it's a really good message because as consumers we need to make better choices," she says.

Thus, she will keep taking her jars and containers to the local bulk store and San Francisco will keep recycling. While in Staunton, Kartseva will continue to reuse the plastic she can, and recycle out of state the plastic she can't.