Yang, from Harbin in China's northeast, came to Japan to study in 1987. What surprised her most was the fact that the Japanese people had the freedom to speak out about politics and society.

Back in China, she was warned of the folly of capitalism throughout her school years. The impact of the Chinese Revolution was clearly reflected in the country's education policy.

Harsh upbringing

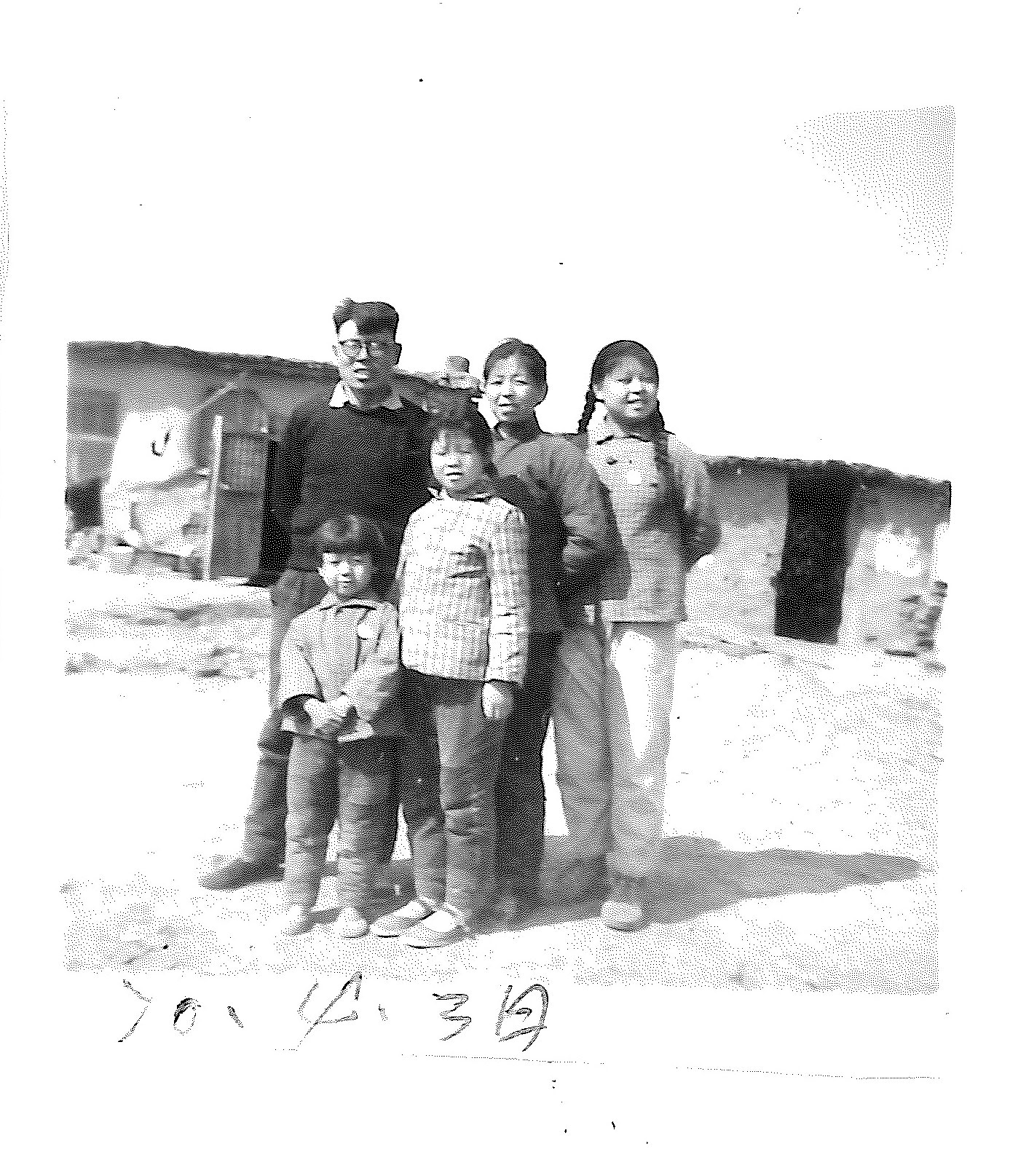

Both of Yang's parents were teachers. In 1970, the family were taken to a remote village north of Harbin to work on a farm while being reeducated.

Their new home was a desolate old house without doors, windows, electricity and running water. The family even had to use their candles sparingly, as they were rationed.

During the three-and-a-half-year period of "thought reform," Yang also had to work, plowing the fields and taking care of livestock alongside the adults.

"As a child, I wondered why we were being forced to work so hard," she says. "But that was a question we weren't allowed to ask."

About two years after coming to Japan, she learned that back in China students were rallying in Tiananmen Square. The news thrilled her, and she thought China might become a democracy at last.

Witnessing history

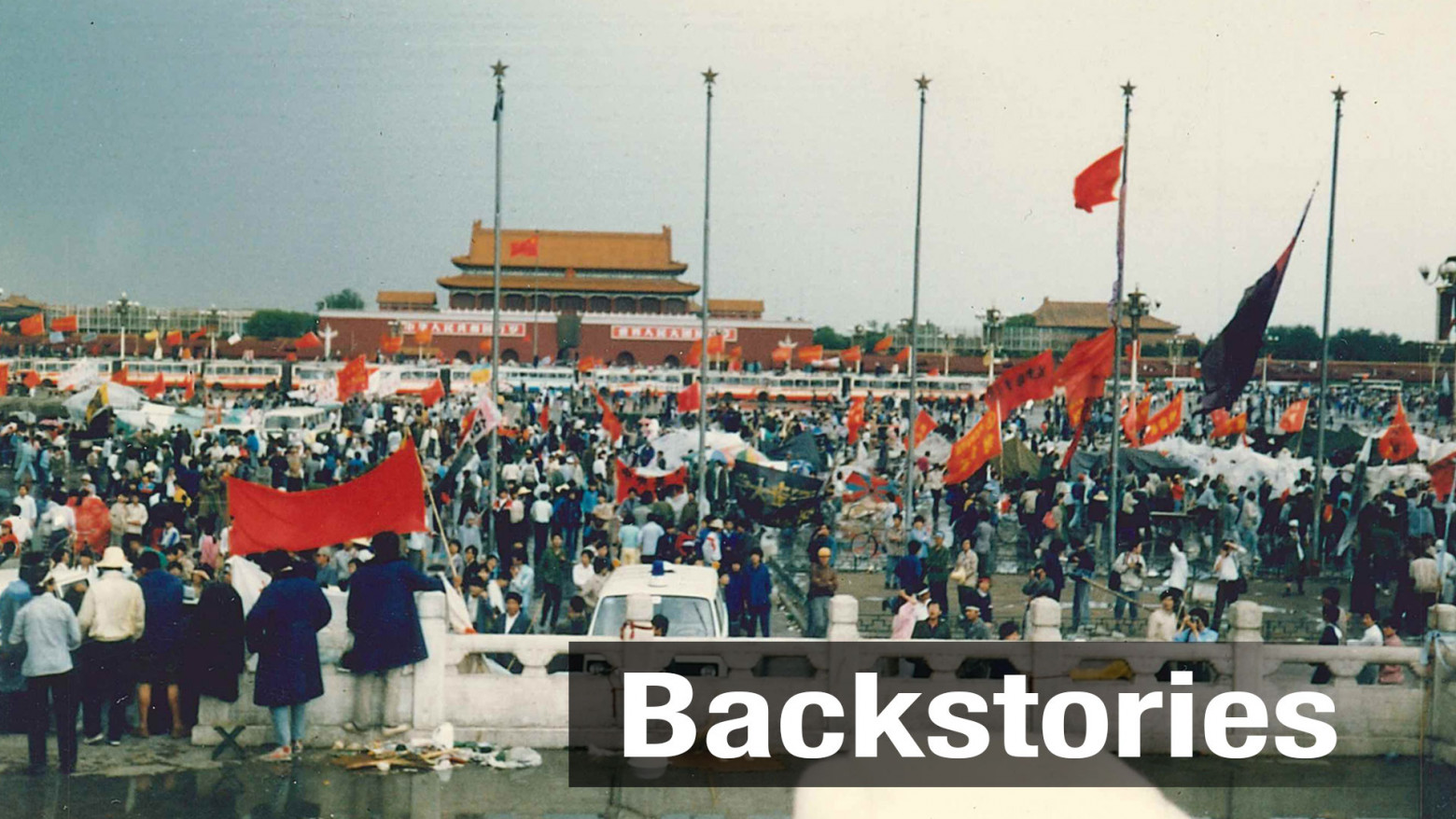

Eager to witness history, she left Tokyo for Beijing on a late-night flight on May 27. On her way from the airport to downtown Beijing, she saw crowds of people in T-shirts and shorts chanting in the street. She had never seen such energy in China.

During her few days in Beijing, she visited the Monument to the People's Heroes, where the students who were leading the protests had made their base. She still remembers the sight when she climbed on the pedestal and looked down. The square was filled with thousands of people.

"All those people were calling for democracy," she says. "It was exhilarating to think that the social suppression that had made us talk only in whispers might be removed."

Yang went home to Harbin to tell her younger sister what she'd witnessed. When she returned to Beijing six days later, she learned that the protests had been brutally extinguished two days earlier.

With local media reports about the incident extremely limited, Yang couldn't grasp what had really happened.

She took a bus to Tiananmen Square, as she had often done before. There was a roadblock, so the bus did not stop at the usual place.

Looking out of the window, she was stunned at the appalling sight. Charred bodies were hanging in the street in front of the square.

The excitement that had filled the square just a few days before had been replaced by complete stillness. Normally, the bus would be filled with conversation, but on that day nobody was in the mood for chat.

Yang felt the authorities had deliberately left the bodies as a warning. Seeing the city's dramatic change first hand, she felt fear and despair.

"No matter how loud the people's voice becomes, this country will never listen to them," she thought.

Lessons from the past

Almost two decades later, Yang's novel based on the incident was published in Japan. The story portrays students who join a prodemocracy movement, only to see their ideals crushed at Tiananmen.

"Since information was controlled at the time, I suspect most young people did not really know what democracy or freedom were," she says. "But things have changed, enabling many Chinese to interact with the outside world through business, study and travel."

"My concern is that a growing number of Chinese people are seeking opportunities outside the country," says Yang.

"I believe they feel that the government's policies are wrong or the country cannot be trusted, even more acutely than people did 30 years ago. It is important for the young Chinese who represent our future to take the issues facing their country more seriously."