Bian Ning, 56, grew up in Beijing, but now lives in Japan, working as a long-distance truck driver. He left China in October 1989 and has never returned. He hasn't seen his mother for 14 years.

Bian joined the People's Liberation Army after graduating from a prestigious university in Beijing. He worked at a military-owned company's weapons transport section.

In 1989, he felt sympathy with the students who were occupying Tiananmen Square, sensing their genuine wish to make the country better. Using a military truck without permission, he and some colleagues delivered food and water to the students.

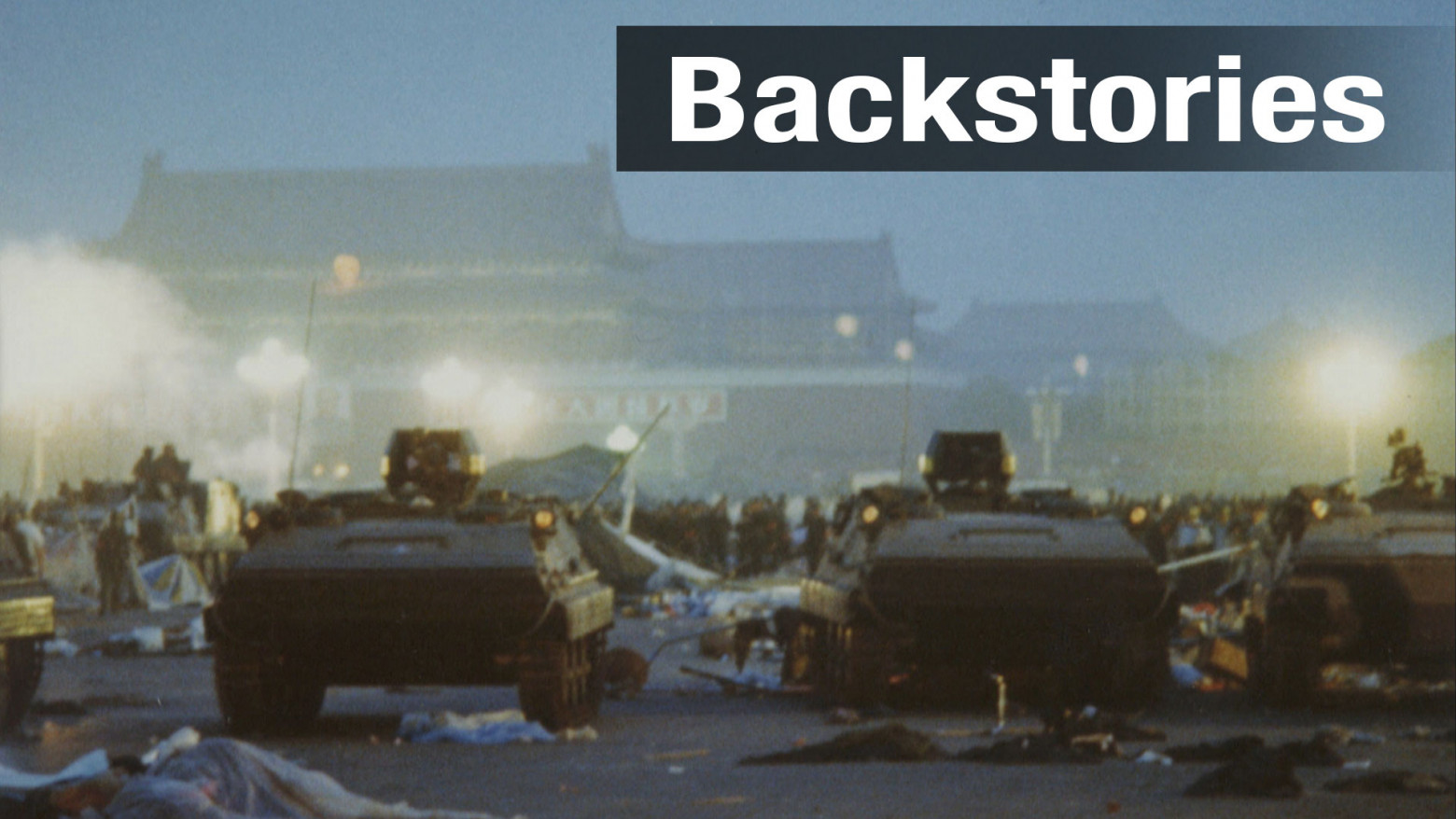

Fateful day

Bian went through many experiences back then, but one in particular remains fresh in his mind.

At dawn on June 4, Bian headed for Tiananmen Square as usual. But he felt the situation was growing ever more tense. He still remembers the overpowering smell of the massed humanity in the square.

About 3 kilometers from the square, all of a sudden, a female student was shot in the head right in front of him. When he shone his flashlight on her, he saw her white shirt soaked in blood. It was clear she had died instantly.

"Is there any need for the authorities to respond as violently as this toward their own people?" he says.

The shock of what he'd seen served only to harden his resentment of the government and the military.

As punishment for his activities, Bian was suspended from work and ordered to stay home. He felt everything he believed in had fallen apart and soon decided to move to Japan.

Leaving China behind

He relied on acquaintances working for public security to secure his passage by ship.

In Japan, he studied the language at a school and joined an organization working to establish democracy in China. He helped publish their propaganda magazines.

Five years after arriving in Japan, Bian visited the Chinese Embassy to renew his passport. However, he was told he would get it only if he agreed to several conditions:

- Bian promises that he will not criticize any policy of the Chinese Communist Party.

- Bian will quit the job of publishing the propaganda magazine.

- Bian will provide the Chinese government with information about everyone working for the pro-democracy movement.

For Bian, none of the conditions was acceptable. He could not betray his colleagues.

Strained family ties

Bian has no major difficulty living in Japan, as he has the right to stay permanently. However, he cannot go back to his homeland without a Chinese passport.

His father died of a brain hemorrhage last year, but Bian wasn't able to see him. "I heard my father kept calling my name even after his condition worsened," he says.

Earlier this year, Bian's 81-year-old mother was able to fly to Japan to see him. When they met at Haneda Airport in Tokyo, he saw that she had aged.

She had tried to visit Japan many times before, but was always given the runaround and never received permission to leave China.

"My husband is dead now," she says. "But I can't live a normal life with my own son, which makes me very sad."

For his part, Bian wants to go back to China to be with his mother, but he knows that's unlikely.

"There's no doubt I would be put under government observation," he says. "That would definitely inconvenience my family and friends, so there's no easy choice."

The 30 years since the pro-democracy movement was crushed have seen China develop in various ways. But many of those forced out by the events of 1989 have yet to see the benefits and remain strangers far from home.