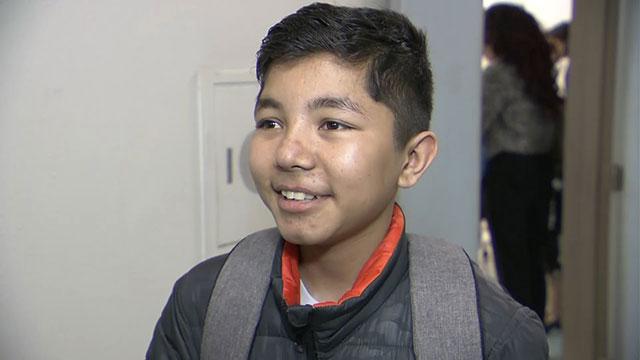

When 15-year-old Sahani Chandra moved from his native Nepal to join his parents in Japan in October, he was hoping to settle into normal life and, like other children his age, enter high school.

The problem was that he couldn't speak Japanese well enough to enter a public school. His parents looked into private education, but it was too expensive.

"Chandra was depressed when he thought there was no school for him to attend," recalls his mother.

Then, in April 2019, a school opened in Chandra's neighborhood specifically for people like him.

The Yoshun branch of Shiba-Nishi Junior High School is one of the early results of a 2016 law. Every prefecture in Japan is now required to have at least one middle school that's open in the evenings and caters to students who have fallen behind.

The idea dates back to the post-war years, when there were many adults whose education had been disrupted by the conflict. They worked in the daytime and joined remedial education at night. The schools have also served those who failed to attend regular schooling for other reasons, such as bullying.

More recently, though, they have drawn students like Chandra. As more and more workers from abroad come to Japan, the government decided to ensure that their children get a proper education.

At the Yoshun branch school, 47 of the 77 students are from abroad. The school is located in the city of Kawaguchi, just north of Tokyo. The city has a foreign population of about 35,000 -- the third-highest in the country -- and the figure is rising.

Principal Akira Sugita says the school is a place where anyone who wants to study can feel safe and learn, regardless of age or nationality.

But it represents a challenge for teachers like Chieko Koike. Some of her students speak some Japanese, while others speak none. For Koike, that was a shock.

"I thought they would speak better Japanese," she says. "I think we'll need to give them individual support."

Currently there are 33 evening middle schools in Japan, spread across nine prefectures.

But demand for places is expected to soar. The government estimates that recent changes to the immigration system, aimed at supplementing the dwindling workforce, will bring in almost 350,000 workers over the next five years, many with families in tow.

As for Chandra, he says he can't wait to get studying. "I'm looking forward to studying at school," he says. "I'll never miss a class!"