NHK recently conducted a study with experts to estimate the number of foreign children not attending either elementary or junior high school. The calculations are based on government surveys on foreign residents and schools.

The study found that around 120,000 foreign children between the ages of 6 and 14 were living in Japan last year. Some 8,400 are believed to have not attended school. These children are not covered by the annual attendance surveys conducted by central and local governments. Under Japanese law, nine years of education, from elementary to junior high school level, are compulsory.

NHK suspects that local governments are unaware of where and how these children are living. Some may have already returned to their home countries or could be attending unauthorized schools for foreign nationals.

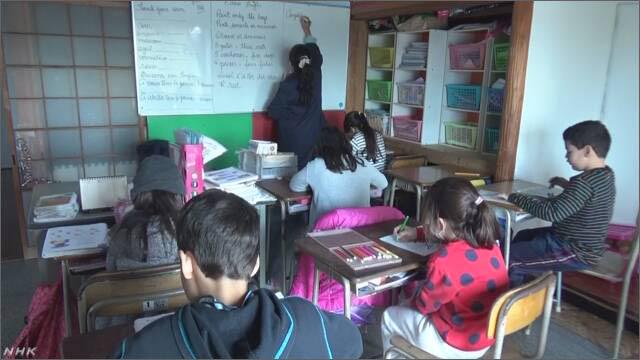

A classroom without a teacher

Maria moved to Japan from Brazil with her parents and younger brother in November 2017. She is seven years old but still goes to the nursery school with her brother Enrique, who is four.

When she arrives at school, she goes to a special classroom for the older children. It has desks, chairs, and a whiteboard. Maria and her older friends study, English, math, and other subjects with Brazilian elementary school textbooks. But there is no teacher.

Maria and the older children have to study by themselves. There are staff members who help but they don't have teaching credentials. The school operates the special classroom under the policy that it offers academic support but not schooling.

Maria's parents, who are in their 20s, work for an auto parts maker as contract employees. They heard about the nursery school from their staffing agency. Their colleagues told them the school is very supportive of Brazilian families who come to Japan for work.

Maria's father leaves home every morning at six to go to a factory in Toyohashi City, Aichi Prefecture, which is about an hour away from Hamamatsu City. He works from 7 AM to 7 PM five days a week. Maria's mother has a job at another factory and also works from morning through evening.

"We rely on the nursery school to look after our children because we have to work long hours to increase our income and stabilize our lives," Maria's father says.

He adds that he was planning to have Maria attend a public Japanese elementary school but changed his mind after someone he knows told him their own children hadn't been able to fit in due to differences in language, culture, and custom.

Maria's father is especially worried about bullying and discrimination. He thought about enrolling her in a private school for foreign students but says it was too expensive.

"We are aware that the nursery school Maria goes to is not an educational facility," he says. "We want our children to get the best education possible, but we don't have enough money to send Maria to a school for foreign children. We know both Maria and Enrique like their nursery school, so we think we'll continue to send them there for the time being."

Hamamatsu authorities are working on a project to get school-age foreign children to enroll in schools as early as possible. They are conducting door-to-door surveys to find children not in school. But convincing the parents is a challenge.

"We can't enroll the children if their parents don't want them to be in school," a Hamamatsu official says. "Children need to learn things appropriate to their age level. We want them to learn in the proper environment, like at elementary and junior high schools, schools for foreign students. If they stay in Japan, they need to get qualifications for high school graduation so they can get jobs. We try to tell the parents how important it is for their children to attend school."

Associate Professor Yoshimi Kojima of Aichi Shukutoku University says the main reason foreign children don't attend schools is because Japan's compulsory education system does not cover foreign nationals.

On the back of new legislation passed in April to accept more foreign workers, Japan's education ministry says it plans to conduct a national survey on the issue of foreign children not in school.

With proper policy and schools that cater to the challenges of learning in a second language, Japan should be able to help children like Maria strive for their dreams.

"Someday, I want to become a doctor and look after my parents," she says.