Falling behind schedule

This is a "transitional storage facility" in Fukushima Prefecture. As the name indicates, it’s a temporary storage space.

The government plans to finish moving all contaminated soil in Fukushima to transitional storage facilities by the end of March 2022, and to remove it from the prefecture by 2045.

But so far, only about 2.4 million square meters of soil—17 percent of the total planned volume—have been transferred to the temporary storage units. The delay is down to problems with land acquisition.

On-site storage

The lack of progress setting up transitional facilities has led to the contaminated soil being stored on-site instead. There are currently 105,000 on-site storage locations throughout the prefecture. They are conspicuous objects covered by green sheets, found in parking lots and in front of houses.

To avoid increasing radioactivity around these on-site locations, the contaminated soil is buried and then surrounded by sandbags, which authorities say keeps it safe. But residents remain uneasy.

"We feel uncomfortable having the contaminated soil around our homes," said one.

"When we see these containers of contaminated matter, covered in green sheets, it reminds us of what happened eight years ago," said another. "We hate looking at them and avoid going near them."

Reusing contaminated soil

The Ministry of the Environment has begun to push the idea of "recycling" the contaminated soil. It plans to transfer soil containing less than 8,000 becquerels per kilogram to be used under roads and in building levees not only in Fukushima but all over Japan.

The Ministry is testing its recycling method at a facility in Minami-soma City. Last December, the Ministry announced that the process would allow up to 99 percent of the contaminated soil to be reused. This means that only 1 percent of the current volume of contaminated soil will have to be permanently disposed of.

"The goal is to complete final disposal, but we have to anticipate difficulties in obtaining land and putting the facilities in place," says Akira Nitta, a Ministry official. "The idea is to make final disposal easier by using the less severely contaminated soil for public works, thereby reducing the amount that needs final disposal."

The Ministry has announced its interest in implementing this policy both inside and outside of Fukushima Prefecture.

Reaction to recycling plan

The Ministry began testing the safety of reusing contaminated soil in Fukushima in 2017. In the village of Iitate, contaminated soil has been buried under fields.

But when tests were planned for Nihonmatsu City, residents were strongly opposed. The Ministry wanted to bury contaminated soil under pathways that run alongside rice paddies.

"Our biggest concern was there’s no guarantee the road won’t crumble during heavy rain, or in another earthquake," said Shunichi Sato, who lives in the area. "Rain will soak the ground. And besides this road, there’s a river that carries water for farming—for the rice fields, a town, and a school. We’re worried the contaminated water would leak."

Last April, the Ministry held an information session for Nihonmatsu residents. I was stationed in Fukushima at the time and covered the event. The Ministry initially banned the press, but residents persuaded the representatives to change that decision. What follows is an exchange we recorded.

Resident: It’s final disposal, isn’t it? It’s not like you’re going to dig it up again and move it elsewhere.

Environment ministry official: We have different plans for final disposal and reuse. This is reuse.

Resident: But you're describing the same thing twice. You're just playing with words.

The 80 or so residents in attendance laughed at the official's responses. They also submitted questions like, "Who decided to hold tests in Nihonmatsu?" and "If the soil is safe, why not use it for public works construction projects for the Tokyo Olympics?"

Ultimately, the Nihonmatsu tests were cancelled last June.

Bunsaku Takamiya is a farmer who attended the meeting. He says his biggest concern was how burying the contaminated soil near crops would harm the area's reputation. "I'm not rejecting the Ministry's data," he says, "but feeling safe and actually being safe are two different things."

"They said they’d dispose of the soil outside of Fukushima, but that’s not what they’re saying now," he added. "They’re talking down to us and saying that it’s safe, that everything’s all right, and this high-handed approach is making us distrustful."

Opposition mounting

After testing was canceled in Nihonmatsu, the Ministry decided to use the contaminated soil to widen an expressway in Minami-soma. But at an information session earlier this month, a number of residents expressed opposition to the plan.

Verifying the safety of recycled contaminated soil will take time. But the ministry needs to proceed the plan while requesting approval with the plan. This is likely to become a tough path.

Not only an issue for Fukushima

The question of how to dispose of contaminated soil is not limited to Fukushima. The same scenario is playing out in seven other prefectures—Iwate, Miyagi, Ibaraki, Tochigi, Gunma, Saitama, and Chiba. And in all of these places, authorities have been unable to find final disposal sites and are keeping contaminated soil on-site. The prefectures plan to dispose of the contaminated material internally, but they haven’t yet determined how.

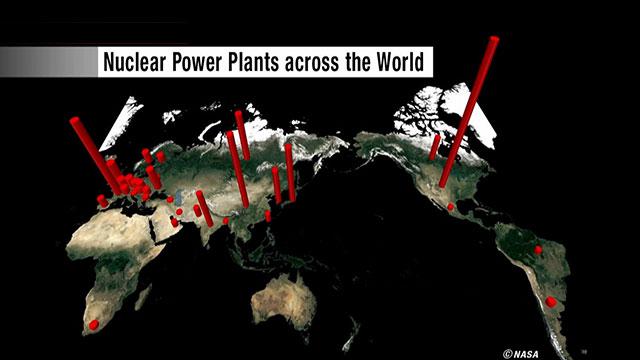

I worked at NHK’s Fukushima Bureau for two years and have continued to cover this story since leaving last summer. The people in Fukushima that I've spoken to all agree that their biggest hope is that the world never forgets what happened here. They say it could happen anywhere. As of January 1, 2018, there were 506 nuclear power plants in operation or being constructed in 34 countries or territories around the world. In the event of a disaster, any of these places could face the same dilemma as Fukushima today.