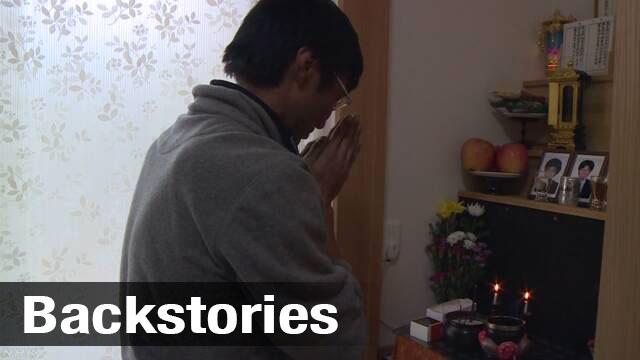

A caring daughter

Hitoshi Ogasawara's 26-year-old daughter, Yuka, worked at the town's welfare division. She was diligent at work and always cared about her parents. As they used to run an after-school care facility, Yuka had always dreamed of working with children. After studying child welfare at university, she had hoped to become a specialist.

After the earthquake struck, Yuka, who was out of office, is thought to have rushed back to the town hall. Later, she was found dead near the building, but where and how she died is still unknown.

Ogasawara had kept quiet on his desire for an investigation for fear of getting in the way of officials working on the town's reconstruction. However, last summer he finally visited the town hall to ask questions.

He says: "An official told me, 'I heard some staff got out of a car here and walked toward the town hall.' That was it. Honestly, I was surprised that was all the information they could give me. I thought I might be able to find more details, if I kept investigating."

Looking back or moving forward?

To this day, Ogasawara regrets some advice he gave his daughter.

"I told her that public servants need to devote themselves to the residents," he says. "Sometimes, you have to risk your life to fulfill your duty. Can you do that? I feel sorry for saying that. I still regret that."

In Otsuchi Town alone, 1,286 people, or almost 10 percent of the residents, were killed. The town hall building became a symbol of the disaster.

Debate about whether or not to preserve it continued for over seven years, but in January a court rejected residents' pleas and paved the way for the demolition work that has now been completed.

As the removal of the building became increasingly likely, Ogasawara became afraid it would become harder to unearth more details about the unexplained deaths. In a meeting between town officials and residents he appealed to Mayor Kozo Hirano to clarify the situation.

Hirano responded: "I will get close to the feelings of bereaved families, as they want to know what happened back then. I will investigate and report on all officials who lost their lives."

A snapshot of the disaster

Yasushi Kurahori is going through a similar experience. He lost his parents, grandmother and brother, who was a town official. Takeshi Kurahori was 30 years old when he died and was relied upon by people around him. The details of his death also remain a mystery.

The only clue is in photos taken after the earthquake in front of the town hall. A disaster control headquarters had been set up there and, as the tsunami approached, it was full of city officials coordinating their response.

Takeshi was in one of the pictures. Kurahori waited patiently for a detailed explanation of his death, but none was forthcoming.

Kurahori says, "As a member of a bereaved family, I honestly want to know where my brother was, what he was doing and how he died."

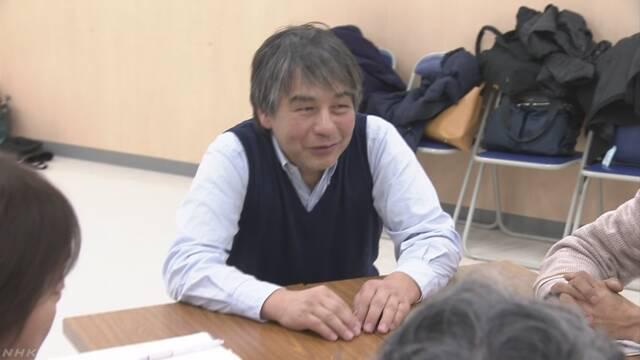

Lack of closure

Tetsu Mugikura who specializes in the Sociology of Disasters at Iwate University interviewed the bereaved family members of 27 out of the 40 town officials who died in the disaster. He says he received the same response from most of those he interviewed.

"Most told me that they didn't know how their loved ones spent their final hours," he says.

Mugikura says the fact that the deaths occurred while the officials were on duty played a part.

"When a death occurs inside a body like a public organization or a private company, there is a tendency to avoid inquiries, as someone may be held responsible or have to pay compensation," he says.

"The situation is typical when accidents happen inside an organization or at the workplace."

For this reason, he says, bereaved family members are having trouble finding closure.

Inadequate investigations

Over almost eight years, the municipal government has twice examined how the town has responded to the disaster and issued reports on the findings. But the documents mainly refer to anti-disaster measures and risk-management, and do not shed light on the staff deaths.

Mayor Hirano has admitted that the town put off investigations into the deaths: "While the town has been responding to urgent needs and other recovery efforts all these years, I think we have not thoroughly looked into workers' deaths. We were aware of the need to do so, but it's true that investigations have been shelved."

In January, town officials said they will try to shed light on the 40 victims by interviewing over 100 people, including workers who survived the disaster, to hear about what they witnessed.

Hirano says, "As the town's leader, I want to visit each of the bereaved families to convey information about their loved ones and apologize to them."

Learning from the disaster

With work to demolish the town hall building expected to be completed by early March, it's important to keep investigating and pass on details about exactly what happened in the disaster, even after the symbolic structure is torn down. Doing so has clear significance for both the individuals and organizations involved.

And Otsuchi Town must ensure that its survey results satisfy the bereaved families. The inquiry should also serve as an important tool to help prevent memories of the disaster from fading, as well as to help boost disaster-preparedness.