So near, yet so far

Sakiko Suzuki, 80, was born in Shibetoro Village on Etorofu Island, one of the four Russian-held islands. She now lives in Nemuro City in eastern Hokkaido. From its shores, she can clearly see some of the islands that make up the Northern Territories.

Soviet invasion

On August 9th, 1945, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan, ignoring the Neutrality Treaty between the two countries. In early September, Soviet troops invaded the islands, including Etorofu, where the Suzukis lived at the time.

Sakiko says when she heard the sound of Soviet soldiers approaching on horses, she was terrified. She remembers that the soldiers, carrying bayonets, stormed into her house without bothering to take their shoes off. They took watches, fountain pens and other valuables and shoved them into their pockets.

Forced to leave home

Sakiko was among the more than 17,000 Japanese people who lived on the islands at the time. Some of the residents fled, while others stayed. The Suzuki family was among the latter and spent three years living alongside the Russians.

But, in 1948, the family was forced to leave by ship carrying nothing but small bags of belongings. Sakiko was sent to a concentration camp at Maoka, now called Kholmsk, on Sakhalin.

She recalls the extreme hardships she encountered there. She had to drink contaminated water, and many children fell sick because of malnutrition. Sakiko says: "I saw people dying one after another. A truck would come every few days to pick up the bodies, but no one knew where they were buried. They were treated like trash."

After about a month in Sakhalin, Sakiko returned to Hokkaido.

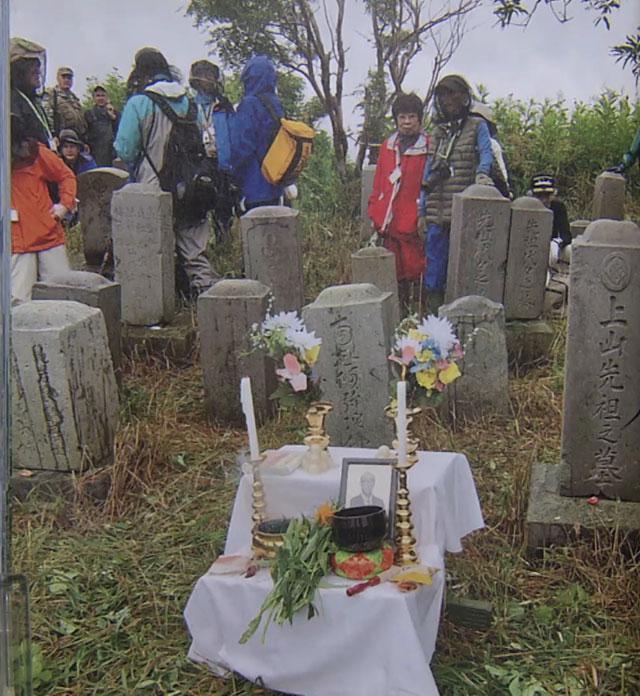

Decades later, a brief return

However, it was not until 1990, more than four decades later, that Sakiko was able to travel to her homeland. For the first time, former residents of Etorofu were allowed to visit their ancestors' graves. She visited the graveyards with her former neighbors, only to see them destroyed, with gravestones scattered everywhere. A Russian guide told her that many gravestones had been used to build new houses, while others remained only because they were not used for construction.

Sakiko says: "Upon hearing that, my anger peaked. No tears or words could express my resentment about that terrible treatment. Everyone there visiting the family graves with me fell silent."

Overcoming resentment

Sakiko says it wasn't easy for her to open up to Russians living on the island. But that changed as she continued to visit the Northern Territories and communicate with local Russians on visa-free exchange programs between the two countries.

When she visited one of the Russian families who lived on Etorofu Island, a young man asked her, "Don't the former Japanese residents hate Russians like us who live here?" The man avoided eye contact as he spoke, but she was struck by his bravery.

Sakiko says: "I was grateful for the mere fact that there are some Russians who care about us. I felt the need to open up and talk about my feelings." She told him what had happened to her family grave, adding, "I have never experienced anything sadder than this."

Sakiko says the young man's mother said Russians also worship their ancestors and that she was ashamed to hear this. The woman apologized with tears in her eyes.

Sakiko says she realized the sincerity of those remarks and couldn't hold back her tears either. She says, "The feeling of resentment I had held onto for such a long time evaporated."

Sharing her experiences

The experience prompted Sakiko to start sharing with younger generations how her family was forced to leave the island. She is hoping that can add momentum to the campaign for the return of the islands. Her audience consists of not only Japanese people, but also Russians visiting Nemuro City from the islands.

Parts of Sakiko's story are painful for Russians to hear, and some of them would leave before she finished her story. But she continued in the belief that it's important to deepen mutual understanding.

Sakiko says: "I'm thrilled when I'm able to get my message across to young Japanese and Russians. It motivates me a lot when they send letters describing how they felt. I read them over and over. I'm also encouraged to know that young people will pass on what I tell them to future generations. So I'm determined to do everything I can to continue speaking about my experiences." She treasures the responses from young people who've heard her story.

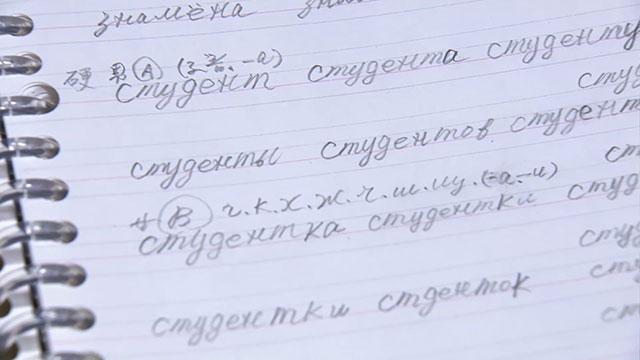

Learning Russian

As Sakiko shared her experiences, she realized the Russians seemed to be more interested in her story when she introduced herself in their language. So she began learning Russian for the first time at the age of 70. She enjoys speaking to the Russians living on the islands using what she's learned. As she built a rapport with them, some began to share the latest news from the islands without her asking.

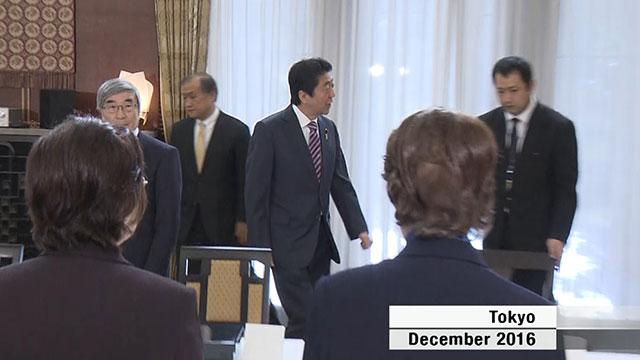

Letter to Putin

Sakiko decided to put her newly acquired skills to good use by writing a letter to Russian President Vladimir Putin. She gave it to Prime Minister Shinzo Abe when she and former residents of the islands met with him prior to his summit with Putin. Abe agreed to pass on the letter, and Sakiko later learned that Putin had read it.

In her letter to Putin, Sakiko made a proposal. She mentioned a salmon hatchery in her hometown, Shibetoro Village on Etorofu Island. The hatchery was built by Japanese islanders in 1929, but the Russians took over the business and ran it until 2002.

Sakiko's father told her that at the hatchery, Japanese and Russian residents had worked side by side after the invasion. He said the Japanese had taught the Russians how to hatch eggs, while the Russians had taught their Japanese coworkers the Russian method for processing salmon roe. He said the Japanese and Russian workers had helped each other. In her letter to Putin, she shared the story and proposed that Japanese and Russians build a facility in which they can cooperate as they did at the hatchery.

Sakiko says she thought Putin wouldn't read the letter if she just asked for the return of the islands. She was determined to use her experiences of living alongside the Russians to solve the territorial issue. She says no matter how hard it was, she thought she should write the letter in Russian so Putin would understand its contents.

Japan-Russia negotiations

Negotiations between Japan and Russia have failed to produce tangible results. At a summit in Singapore in November 2018, Abe and Putin agreed to accelerate talks towards a peace treaty based on a 1956 joint declaration. The declaration stipulates that Moscow will hand over Habomai and Shikotan to Japan after the conclusion of a peace treaty. But there's no mention of Etorofu, Sakiko's birthplace, or Kunashiri.

Sakiko says she's always wanted all four islands to be returned to Japan and she still feels that way. The leaders of Japan and Russia met again in January this year, but the two sides remained far apart. The Russian side reiterated that Moscow will not sign a peace treaty unless Japan recognizes Russian sovereignty over the islands. Japan has maintained its official stance.

Sakiko fears that the talks might stall. She says: "I am getting older each day. So, to be honest, it's really tough. I've been working for the return of the islands all these years, but this is the hardest it's been. We feel uneasy but all we can do right now is to wait for a positive result."

Passing on the torch of hope

Sakiko pins her hope on her daughter, Takako Yamashita, who's 55. Yamashita never lived in the islands, but she delivered a speech at this year's National Rally calling for the return of all four as a second-generation former islander.

In her speech she said, "My mother, who was ten when she was forced to leave the islands with her family, is now 80. Too many years have passed. Former residents of the islands have strong feelings towards their hometowns. They say not a day goes by without thinking about the time they spent on the islands. I only hope that a day will soon come when we can all stand on the beach of Shibetoro Village together, filled with joy, and shout, 'We're home!' To make that happen, I'd like to ask for your cooperation." Her mother sat in the front row, listening as tears filled her eyes.

After the speech, Yamashita said that her mother's age means little time is left to resolve the issue. She pledged to make every effort to make the campaign a success so the islands are returned as soon as possible.

Sakiko says she was moved by her daughter's speech and was relieved to confirm that she had fully understood her mission. She says she wants her to take over when she is gone.

Yamashita, who is a music teacher, played "Furusato (Hometown)" on the piano when I visited her home in Sapporo. She played powerfully, as if to show the strength of her resolve to carry on what her mother began.

Former islanders sing this song at the end of each visit, as they look out from their boats at their hometown disappearing into the distance. Many say they want to live alongside the Russians, rather than force them out of the islands. I couldn't help but hope that a day will come when Japanese and Russians can sing together in a shared home in the islands.