In recent years, however, the meteoric rise of the konbini has ground to a halt, the stagnation a barometer of fast-changing demographics.

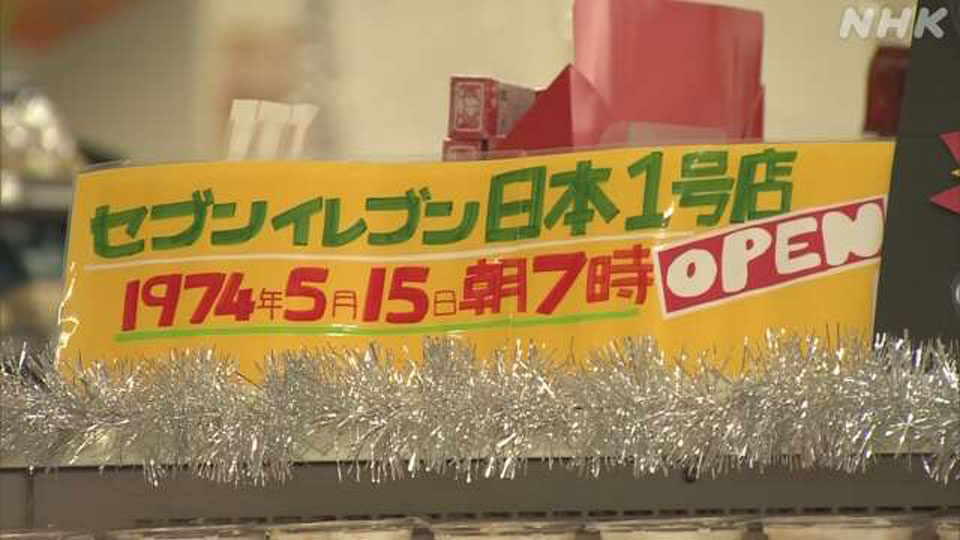

It was in 1974 that Japan got its first 7-Eleven outlet—in Tokyo's Toyosu district. "It's only because of our customers that we've been able to stay in business all this time," said franchise owner Yamamoto Kenji, 74, on the shop's 50th birthday in May. "As a cornerstone of the community, our goal is to keep the trust and appreciation of the people who live around here."

Feeling flat

Seven-Eleven Japan was the first convenience store chain in Japan to launch a nationwide franchise system. Lawson and FamilyMart followed, also in the 1970s.

Fast forward to this year, and the number of konbini nationwide has ballooned to more than 55,000, according to the Japan Franchise Chain Association. Together in 2023, they rang up 11.6 trillion yen in sales.

In recent years, however, the growth in numbers has fizzled out as Japan's declining population has forced chain operators to look to overseas markets in search of better opportunities.

A mirror to society

Over the years, the convenience store has provided one of the most accurate reflections of Japan's social and demographic trends, with its changing lineup of products and services serving as a guide to the way people of each generation have lived.

The big chains adapted early on to Japan's notoriously demanding working hours.

"Today, it's standard for convenience stores to be open all the time," says Taya Shinji, an expert on Japan's favorite place to shop, "but it was only in 1975 that 7-Eleven stores began operating 24 hours. Staying open all day and night meant surrounding factories could also stay open. It improved efficiency."

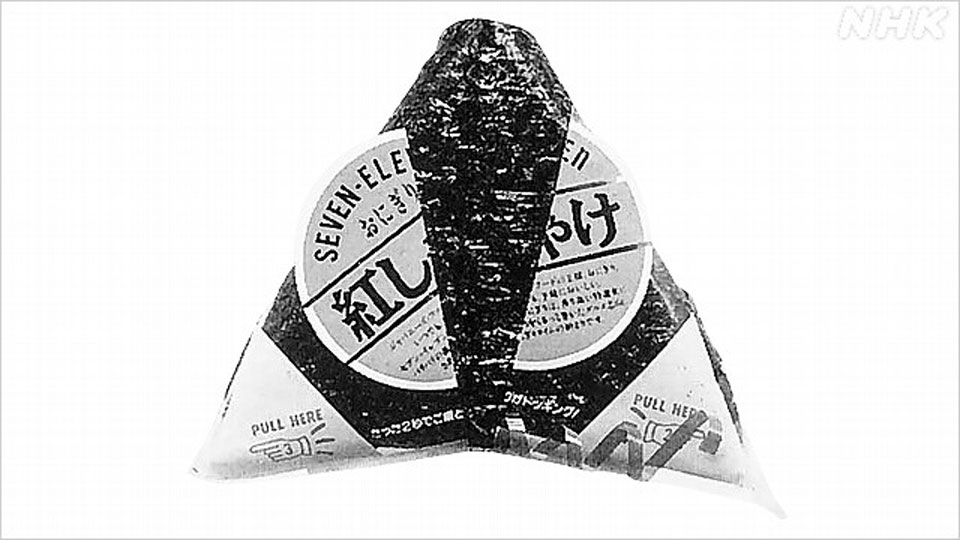

Convenience stores soon began to offer cheap and warm meals, prepared on site, that busy office workers could shovel down fast ― at their desk or in a nearby park. Onigiri rice balls, cheap and filling, were another essential fuel source.

Taya says during the Bubble era of the late 1980s, when slogans such as "Can you fight 24 hours?" became famous across the country, people were even more grateful to have shops that stayed open round the clock.

A one-stop shop

As the '80s turned into the '90s, the range of services that konbini offered expanded dramatically. Now people could use them to pay their electricity bills, receive packages that would usually be delivered to their homes, or withdraw cash from ATMs, among other things.

"It became a cycle," says Taya. "As the stores became more useful, more people used them, and that in turn led to an increase in outlets."

In the 2000s, convenience stores became more ubiquitous still. It was in this era that chain operators started developing their own lines of products and introducing loyalty programs.

Part of the social infrastructure

"Convenience stores change as society changes," says Yoshioka Hideko, a journalist who has been writing about konbini for more than 20 years.

She says it was around 1989 that the shops came to be viewed by most people as an essential part of the social infrastructure. That perception grew stronger in the 2000s, and finally became fundamental in the wake of the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami and, more recently, during the coronavirus pandemic.

"During the 2011 disaster, convenience stores stayed open and people realized they could find things like milk and other essential groceries there," she says. "And during the pandemic, people who used to eat three meals at office cafeterias started going to convenience stores near their homes instead. The stores even had a delivery service."

Yoshioka says convenience stores offer a vital window into the world around them.

"There was a time when konbini were described as 'refrigerators' where busy office workers bought drinks," Yoshioka says. "But with the aging and shrinking population, the focus has shifted. Now they offer community services, such as mobile sales for elderly people who live alone and have trouble getting out to do their shopping. The principle of making a profit is still there, of course, but there's something more.

"The fact that convenience stores have been indispensable for Japanese people for 50 years is proof that they continue to evolve with the times."