A report shows that India's rapidly expanding middle class will likely account for 60 percent of the population by 2047 — and there are signs of this newfound wealth everywhere you look.

Japanese clothing brand finds footing

The country's upwardly mobile, for example, increasingly shop at Japanese clothing brand Uniqlo. A branch in Gurugram near New Delhi was buzzing in May. One customer, who told us he's an engineer, says wages are on the up for people in the business sector.

Browse the aisles of a drugstore and you will probably find the baby care section well stocked with disposable diapers. A lot of people have more money now, and they're eschewing the cheaper cloth types.

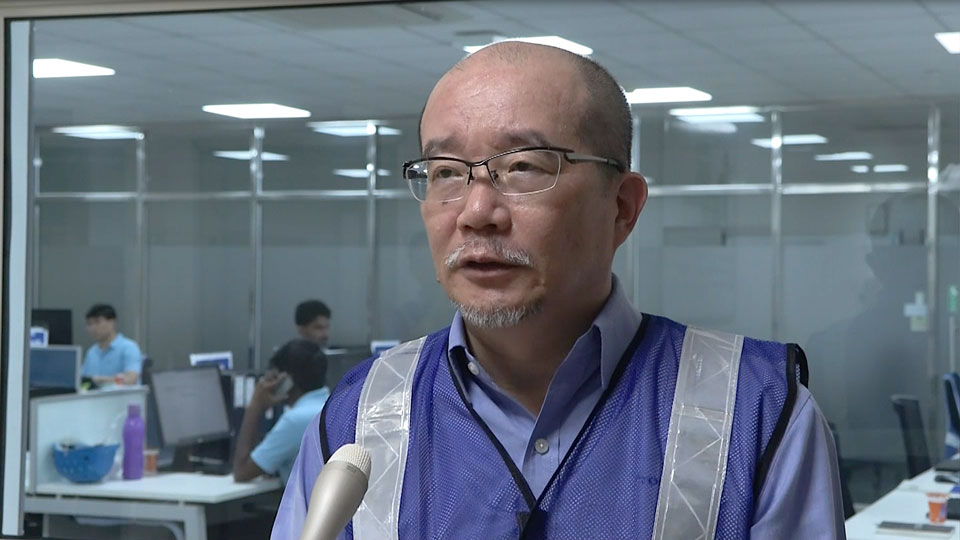

The trend has been a boon for Japanese company Toray Industries, which produces diapers at a plant in the southern state of Andhra Pradesh. Output has risen for four years straight.

"Demand is increasing, apparently because of the growing economy," says senior official Nishizawa Masahiro. "I hope our business expands in line with society."

Good times for some. But many others are mere bystanders. Unemployment is rife among India's younger generations, forcing countless people into gig work.

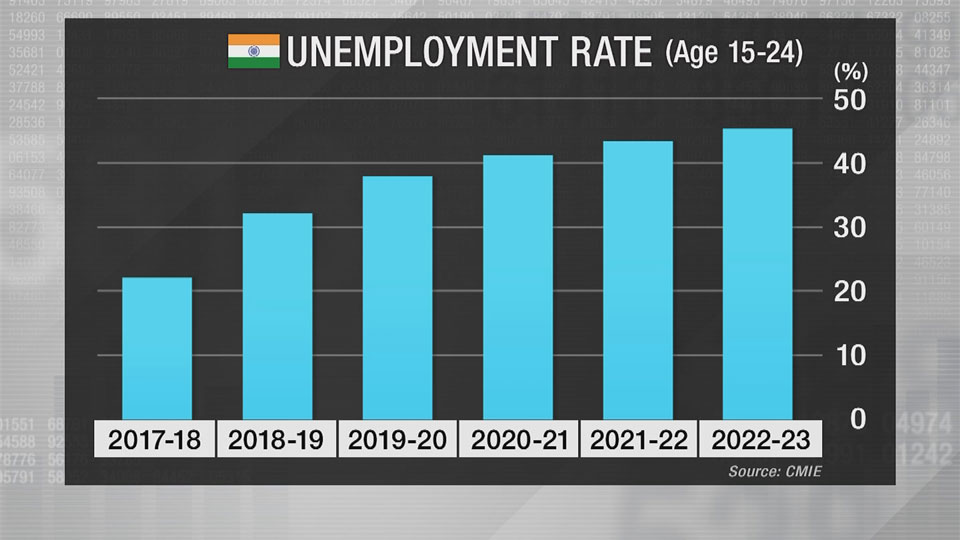

A think tank in India, the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), estimates that the unemployment rate in the 15-24 age bracket during 2022-2023 topped 45 percent, double that of five years earlier.

Graduates left wanting for stable work

New Delhi resident Sumit Sharma has a degree in science and mathematics, but he's failed to land a job in his area of expertise. Instead, he delivers groceries on his bicycle.

"Modi is increasing the number of factories, but there are no places for me to work," says Sharma, who admits to riding in a suit, just in case an interview appears out of thin air.

'Make in India' policy struggles for traction

Azim Premji University Professor Amit Basole says the sectors that have been driving growth in the world's most populous nation are not known for their high volumes of human resources. "Indian manufacturing for example, has not grown as much as we expected," he says. And successes like the auto industry are thanks in no small part to automation.

Basole says the government's Make in India plan, trying to boost manufacturing domestically in fields that have been creating jobs in developing countries, has fallen well short of generating the 25 percent of GDP that Modi was targeting.

"The bottom line is that we are not where we would like to be in terms of being competitive in a global sense in manufacturing," says Basole. "So part of the increase in inequality has to do with the lack of good, productive employment opportunities at the bottom, not just for educated people."

Modi gave a television interview during the election, using his time on air to insist employment opportunities are being created. He also dismissed the opposition's claims of mass unemployment.

Either way, the statistics — and the results of the vote — suggest he has his work cut out.

The World Bank says India's GDP per capita stands at about 2,400 dollars, far below more developed countries. And a survey by the International Labor Organization shows that as recently as 2022, unemployment among graduates stood at nearly 30 percent.

Modi has proclaimed his job creation policy a success, but the data fails to back up that view. Young people are demanding jobs ― and they want them now.