It's 6 o'clock in the morning and 10-year-old Jyoti Kumari walks to Shaheed Arakshi Middle School barefoot. She lives in the eastern state of Bihar, one of India's poorest regions.

Jyoti gets to class on time ― but there's no teacher because there aren't enough of them.

Government primary schools reportedly have hundreds of thousands of teacher vacancies. Poor working conditions and stress are said to be putting people off the profession.

The teacher shortage is expected to worsen in the coming years amid inadequate funding for the education sector.

The Annual Status of Education Report 2023 finds a quarter of India's rural teens, aged between 14 and 18, can't fluently read their language at a primary school level.

Pushapa Sharma, principal at Shaheed Arakshi Middle School, says she has just five teachers on staff for the 204 students. One in five pupils can't read and write, but with more teachers, the students could learn more.

Jyoti's mother Nisha Devi wants her daughter to study hard, so she has the tools to pull herself out of poverty.

"We are poor, so public school is our only choice. But teachers don't show up to classes and they don't teach seriously. Jyoti's Hindi ability is weak. What should I do? We're not rich, we can't afford private school," says the worried parent.

She says the family is desperately poor, noting their income has not increased during the decade that has passed with Modi in the country's top office.

Non-profit groups step up

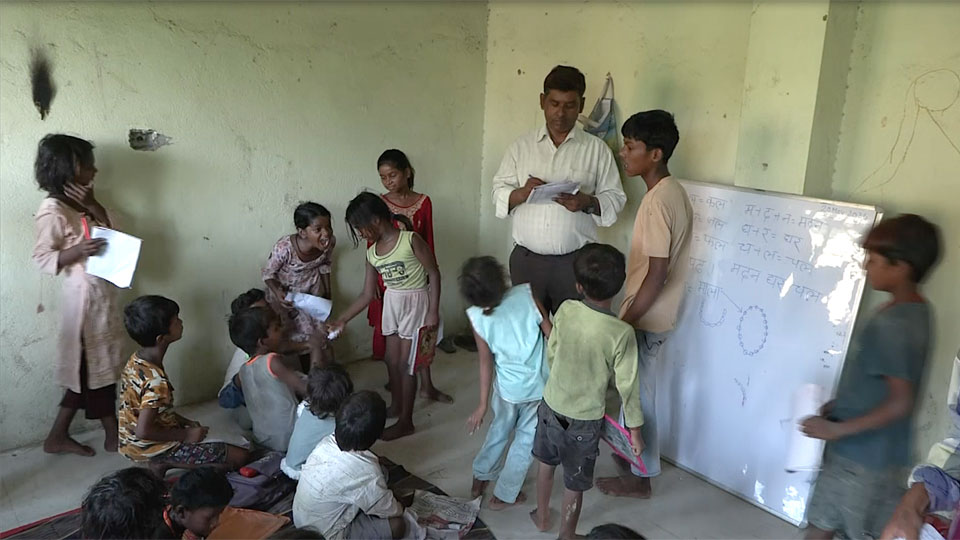

Non-profit groups are stepping up to help. The Musubi-Te Foundation, founded by Japanese man Fukuoka Kotaro. The 34-year-old set up the NPO in 2021 to help people facing poverty due to poor access to education. The NPO offers free after-school lessons, six days a week.

University students and private school teachers instruct participants in Hindi and basic math.

One of the free sessions is held in Gaya city. Jyoti is one of about 1,200 children taking part and she is learning how to read and write "going home" in Hindi. The students are in good spirits and eager to learn.

Fukuoka says, "Children can't focus on studying because of the circumstances they are born into, and it's unfair they are forced to give up on a better life." His foundation's operating costs rely on donations, but more funds are needed.

Long-standing support from Super 30

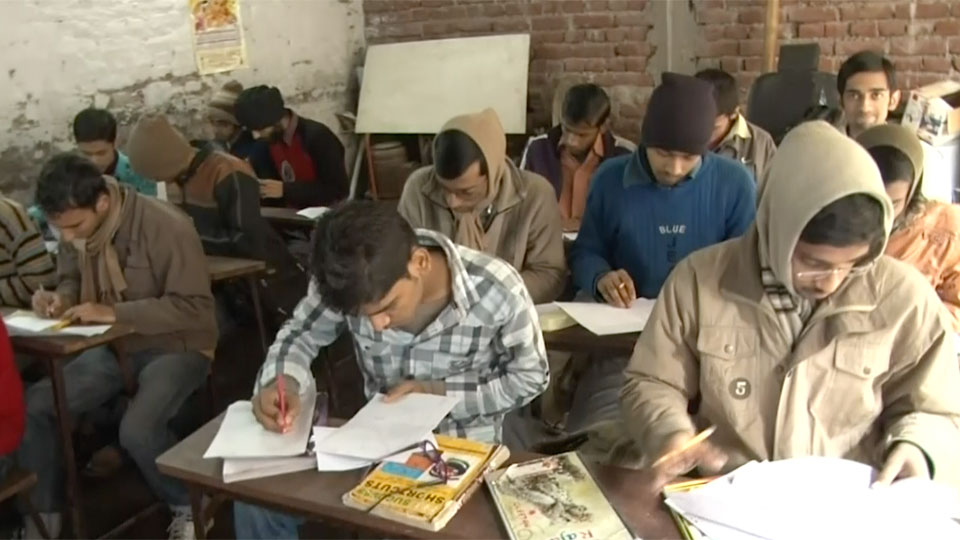

Another program called Super 30 is a highly ambitious and innovative educational initiative. Although it is suspended now due to the influence of the coronavirus pandemic, the program has been fostering students from poor households whose talents might otherwise remain buried without access to good education.

It selected 30 young people each year and offers tuition, dormitory housing, and food, all for free.

The program was started in 2002 by math teacher Anand Kumar. He was once a talented student himself who was accepted into Cambridge University. But his family circumstances prevented him from attending.

Kumar maintains "education is the only way to come out of poverty."

Kumar wants the government to focus on education and train more teachers, with India's future in mind.

Out of 510 Super 30 students, 422 have passed the entrance exam to the country's top university, the Indian Institute of Technology.

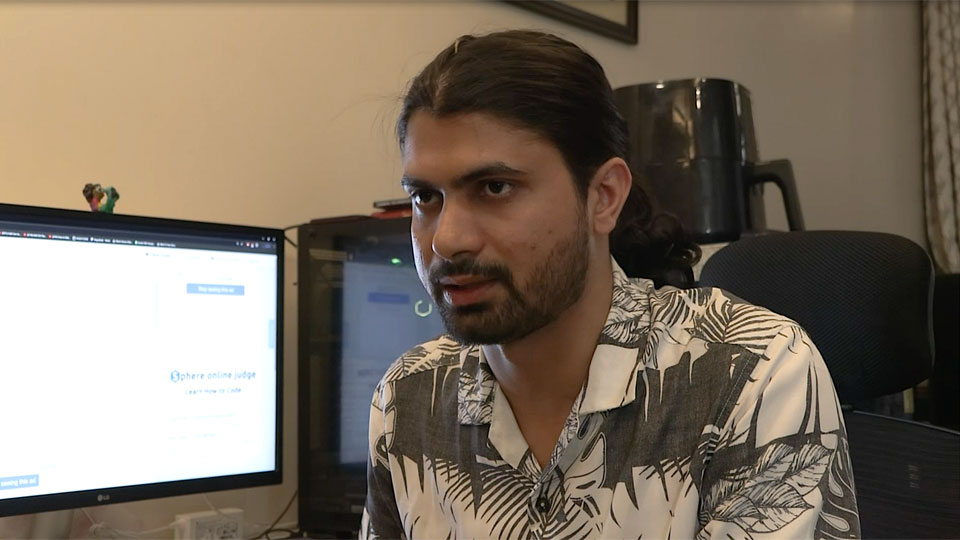

Among them is Hari Mohan Pandey, 28 years old.

He became a software engineer and has worked for high-profile firms, including Amazon. Pandey says Super 30 changed his life entirely. He now earns a salary that would have been unthinkable without the program's support.

Kumar has plans to launch online lessons to reach more impoverished young people. But he insists the government must do more to help.

Education in crisis

In Bihar, there are still many public schools lacking basic facility such as chairs, desks, electricity and water. Millions of children are enrolling across the country but there's not enough funding to support them.

The education system is in crisis, deepening the wealth gap. A recent paper from the World Inequality Lab shows one percent of India's richest citizens own 40 percent of the country's wealth.

The quality of learning at public schools in rural areas is said to be far lower than at private institutions where students can also learn English. Some rural children can barely acquire even mother-tongue literacy.

Modi's ruling party-led alliance maintained a majority in the general election in June. In its manifesto, the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party has a focus on education infrastructure and teacher training.

The government's National Education Policy states that through high-quality education for all, India can become a global knowledge superpower.

In the meantime, children like Jyoti are relying on non-profit groups to help them acquire basic literacy and math skills.

Millions of other students just like her are standing by to see if the Modi administration can deliver on its promise and ensure education is indeed the backbone of economic growth.