The number of children a woman is expected to have during her lifetime fell to 1.20 in 2023. In Tokyo, the figure stands even lower at 0.99.

According to a Japanese government survey, 60 percent of respondents feel it's difficult to be a parent in Japan. Many people struggle to afford children and manage the intense demands of Japanese work culture.

Household finances a barrier

A Tokyo woman in her 30s, who doesn't want to disclose her name, works from home. It's been about a year since she switched from a coveted civil servant career to the municipal government, a job that means she works late every night.

She was recently married and has always dreamed of having two children. But that hasn't happened yet — and the main reason is household finances. The woman is a diligent bookkeeper and keeps close tabs on what she and her husband spend each day. They are both paying off student loans, and recovering from the cost of their wedding.

She feels money is just too tight for a baby. "I think about paying for the delivery and the costs afterward, and I also want to send them to cram school. I tend to worry about the future," she explains.

She also takes on most household duties. Her husband, a teacher, works long hours. He comes home late, then studies for an exam that could earn him a promotion and higher pay. They have very little time to talk about starting a family.

"Both my husband and I really want to have kids right now. But I worry about our finances and how my husband and I will split the housework, so I wish I could make those concerns go away," she says.

Juggling work and family

Even for families with secure finances, juggling work culture with parenthood is no easy task.

"I just finished meeting with a client. Now I'm off to pick up my son," says Matsunaga Yuki, 40, who has a 1-year-old son. She is deputy head of sales at a life insurance company and excels at work.

That success in the workplace provides a sense of pride. "I used to think about my job 24 hours a day before having a baby," she recalls. "I want to keep working for the rest of my life."

Maintaining the hustle requires precise time management. She works until about 8 p.m. every night, including Saturdays, just like her colleagues. Her husband, a business owner, is home even less.

It's up to Matsunaga to pick up their son from daycare, leave him with a nanny, and return to work. She has about three hours on workdays to spend with her son and makes sure that's quality time together.

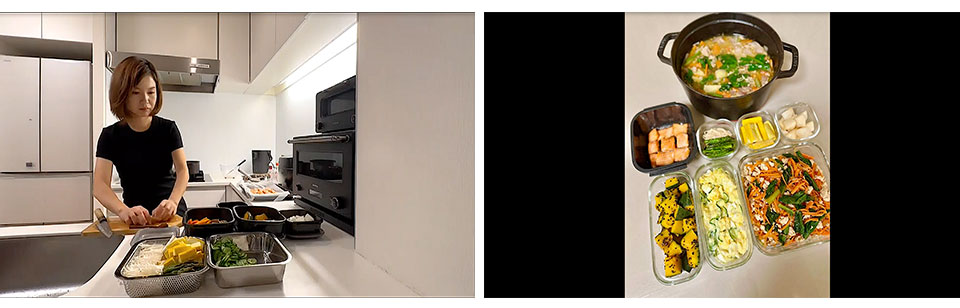

On Sunday, her only day off, Matsunaga preps about 20 to 30 child meals for the following week. It's one of the ways she connects with her son.

A lot falls on her plate: "Even when both parents work, I feel like the mom has more tasks… Japanese mothers, including myself, take our roles very seriously, and that's why we do our best," says Matsunaga.

"We want to make everything perfect, and that puts a lot of pressure on us. I'm always seeking the right choice for my family."

Cost and time

While having kids is a personal choice — and not for everyone — people who do want them are struggling. It's not just the financial cost that serves as a deterrent, but also a lack of time. Many Japanese workers are expected to put in long hours.

The Japanese government survey quizzed couples who did not have as many offspring as they'd like. Some of the respondents cited finances, and others said they were worried about having children at an older age.

Many also said they couldn't handle the psychological and physical burden of childcare on top of their existing lives.

Government's new childcare policy

Japan's government is trying a raft of measures worth more than 23 billion dollars per year to encourage people to have more children.

Family allowances are being increased to up to about 200 dollars per month per child up until they are 18, regardless of household income. More money is available to support parental leave and birth expenses.

In some area, child daycare is now open to anyone instead of being restricted to families where both parents work.

Expert: Fathers need to step up

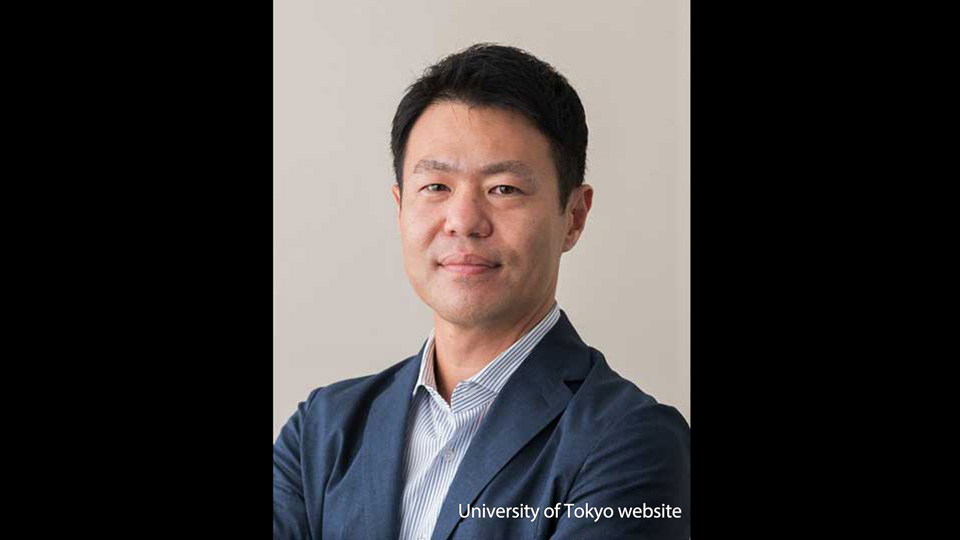

University of Tokyo Professor Yamaguchi Shintaro is an expert on labor and family economics. He says the government’s measure would be among the top child-rearing support programs in the world. But he is still skeptical that it would lead to a recovery in the birth rate.

"Many countries have tried giving out a bonus for each birth. The birth rate does go up, but only marginally. Money makes it easier to afford having kids. But if the goal is to raise the birthrate, I don't think it will solve the problem," he says.

Yamaguchi points out that fathers' participation in childcare could be key.

"Fertility rates are falling in many developed countries. However, I think Japan has a lot of room for improvement when it comes to the gender gap at home. Women spend more time on housework and childcare than men — five times more. That figure is much higher than in other developed countries. If men were more present in childcare, like in Western countries, we'd get closer to the solution."

Yamaguchi adds that corporate culture needs to change, beyond addressing long working hours. Government figures show only 17 percent of new fathers took parental leave for an average of 46 days. It's a situation that is unlikely to change unless top management is on board.

Time is running out for Japan to address its falling birthrate. Researchers estimate the loss of 30 percent of the population by 2070. To achieve a sustainable society as a long-term goal, barriers that keep people from having children need to be knocked down.