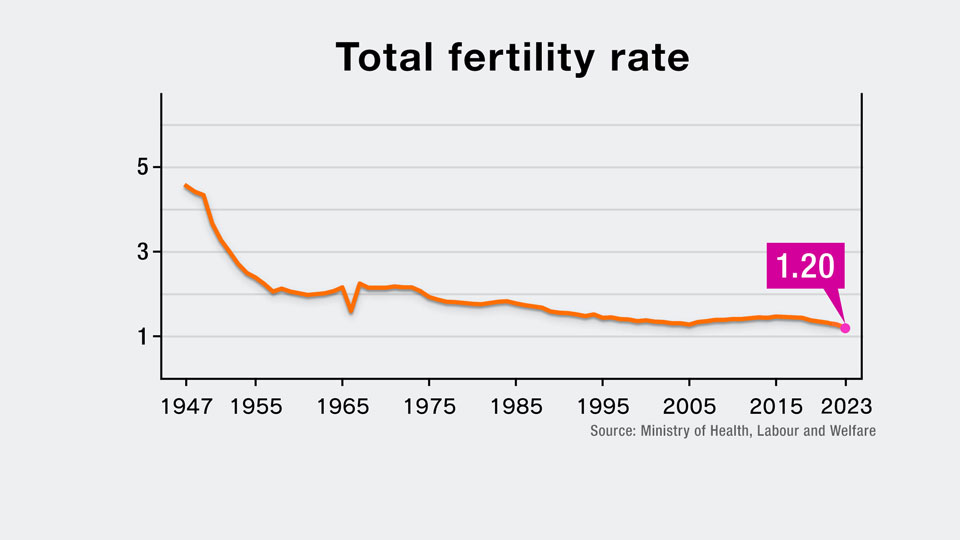

Preliminary demographic statistics for 2023 released by the Health Ministry on Wednesday show the total fertility rate ― the number of children that each woman is expected to give birth to in her life ― declined 0.06 points from the previous year to 1.20. It was also the eighth straight year-on-year fall.

The rate dropped in all prefectures. Tokyo posted the lowest of 0.99. Next was Hokkaido at 1.06, then Miyagi with 1.07. Okinawa had the highest rate of 1.60, followed by Miyazaki and Nagasaki at 1.49 and Kagoshima with 1.48.

A rate of 2.07 is considered necessary to maintain a stable population.

The number of Japanese babies born last year was also an all-time low. It fell 43,482 from a year earlier to 727,277, the fewest since records began in 1899.

Ministry officials said the declining birth rate is in a critical situation. They pointed out that the last opportunity to reverse the trend is the period up to 2030, as the young population is expected to drop sharply after that.

Working fathers' burden

Some young parents ― including 31 year-old Horikiri Shuhei, who is raising a 3-year-old son together with his working wife ― feel that the demands of work have a lot to do with the declining birthrate.

"It's a race against time every day to handle work and child-rearing,'' Horikiri says. ''We've realized that it takes so much to raise a child when both parents are working."

He used to work for a manpower dispatch firm. In order to take his son to day care and pick him up, he would start working at 7:30 a.m., and leave the office at 6 p.m. Once at home, he had to deal with unfinished work late at night or early in the morning, in between looking after his son. Horikiri only managed to juggle his day job and parenting by cutting down on sleep.

In February, after feeling that he had reached his limits physically and mentally, Horikiri decided to change to a job which allows him to work at home.

Horikiri says the idea of having a second child was unthinkable when he was expected to work long hours.

"My hands were already full with one child and I couldn't even consider the possibility of having another," he says.

Many young parents echo Horikiri's struggle. The father of a 4-year-old girl says his wife is looking after their daughter by herself due to his long overtime hours. The mother of two boys aged 6 and 3 says her husband works from home, and she is working reduced hours to cope with child-rearing, but it would still be difficult for them to have another child.

The burden on working fathers is clear in the findings of a recent survey of 1,500 fathers conducted by Tokyo's Toshima Ward, which had the lowest birthrate out of the capital's 23 wards.

Eighteen percent of respondents said work took up 12 hours or more of their day, including commuting. Forty-five percent said they felt a mental burden before their child was one-year-old.

Officials and experts believe that long working hours is a major factor contributing to the stress of child-rearing.

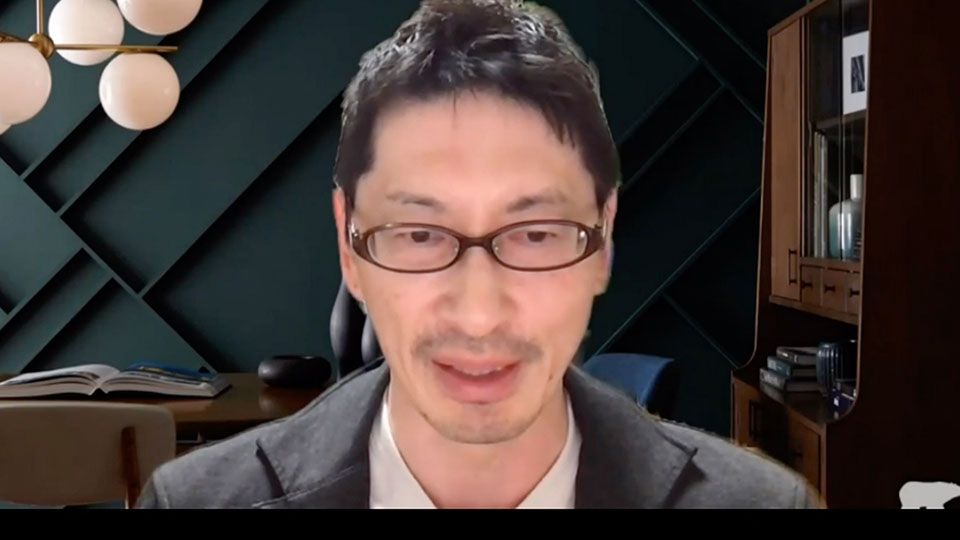

''The real key to redressing the declining birthrate is to change men's work commitments rather than women's," says Ritsumeikan University Professor Tsutsui Junya.

He says companies place a heavy burden on their male employees on the assumption their wife is at home taking care of the children. ''It's important to change this."

Company's initiatives make a difference

Some companies are trying to reduce their employees' working hours without compromising productivity.

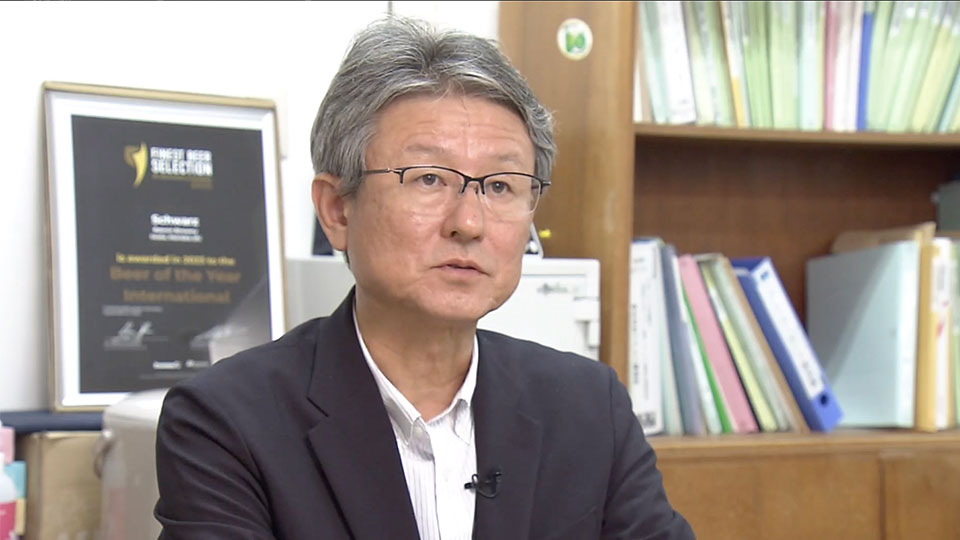

Baeren, a craft beer company in Morioka, Iwate Prefecture, northern Japan, has even seen an increase in the number of children born in its employees ' families following changes it made.

Seven years ago, company president Shimada Yoichi embarked on work-culture reform as he noticed that female employees had been forced to leave the front line after becoming pregnant.

"Amid a labor shortage, I thought creating an environment that makes it easier for everyone to work was necessary for the sake of my company's sustainability," Shimada says.

Baeren closed an outlet with late-night operations that had led to long working hours, reducing employees' overtime by about 30 percent.

It also introduced a smartphone app for employees to receive vouchers if they agree to cover those who take leave. The app also allows staff to share their duties and assist colleagues with heavier workloads.

Shimada says over time, employees became motivated to complete tasks more quickly, resulting in a 50 percent increase in sales.

The number of children born to employees' families used to be around one per year, but it increased to five last year.

"Businesses cannot change immediately, but I'm convinced there's always something that can be done by any company," Shimada says.

New legislation to expand child support measures

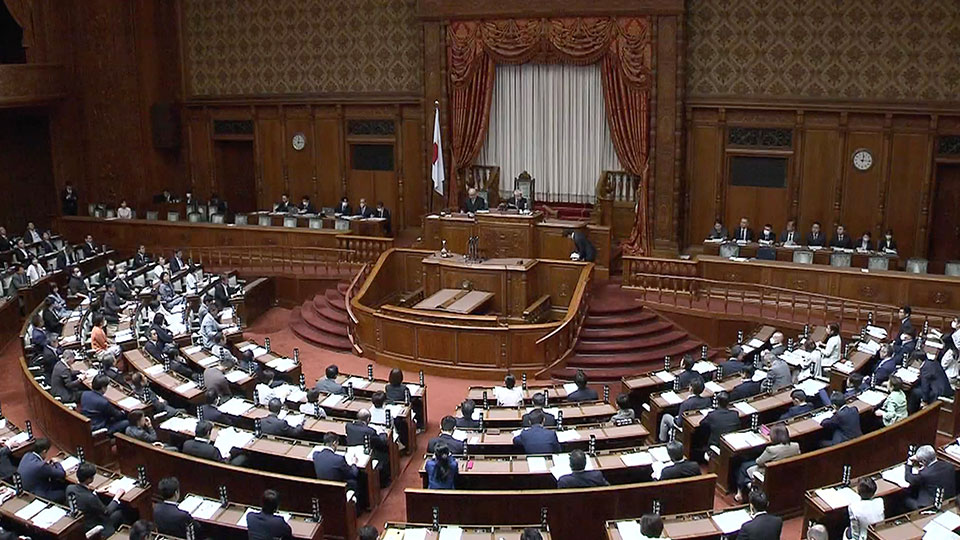

Japan's Diet on Wednesday passed a bill to revise laws on child-rearing support.

The revisions are aimed at expanding existing support measures. The income limit for eligibility to receive the child allowance has been abolished, and the allowance will now be paid until a child reaches 18. A lump sum of 100,000 yen, or about 640 dollars, will be paid for both pregnancy and delivery.

Parents will also be allowed to apply for day care for children under 3 even if they are not working.

The government estimates the measures will cost 3.6 trillion yen a year and plans to have secured the finances to fund them by fiscal 2028.

One source of revenue will be a surcharge on the public health insurance premiums of individuals and companies.

The government says the new system will not create an additional financial burden due to spending reforms and wage increases. But the opposition bloc says reforms to social security expenditure will be limited, so the new system is certain to impose an additional burden on people and businesses.

Expert: Financial burden should be spread evenly across society

Professor Yamaguchi Shintaro of the University of Tokyo's Graduate School of Economics says the government must carefully explain and seek public understanding.

''While measures to address the declining birthrate will benefit parents in the short term, Japanese society as a whole will eventually benefit, so the burden should be distributed evenly,'' he says.