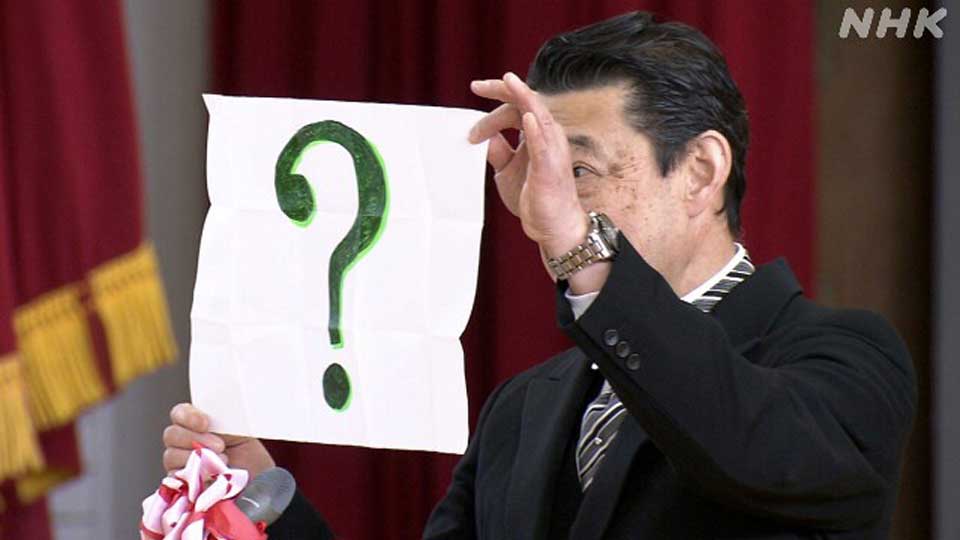

The principal of Yamagata Prefecture's Nisshin Elementary School, Asai Jun, took the bold initiative in April 2023. When he welcomed the 64 new first-graders this year, he told them: "Instead of being forced to study, I want you to find what you really want to know, and think and learn by yourself."

Respecting independence

Homework is common at most Japanese schools although it is not required by law.

Asai, who has four decades of teaching experience, has taken part in workshops overseas and heard education experts speak about the importance of fostering children's independence.

That led him to reconsider learning methods at his school, which has 500 students.

"Adults may feel relieved if kids are doing their homework, " Asai says. "But homework can easily become a task whose only purpose is to be turned in without thinking. I wondered if this really benefits the students, and if they actually gain the ability to learn."

By scrapping homework, he wants children to "think and learn on their own about what they want to do, and what they are interested in."

Instead of homework, the school offers optional handouts that allow students to review their lessons on their own.

"We are repeatedly telling the children that we still want them to study," Asai says. "We expected that students would take one or two handouts, but some are taking as many as 10."

"I can clearly see that they are much more motivated when they are allowed to choose their own homework than when it is given to them."

Allaying initial doubts

Before introducing the no-homework policy, Asai set up dozens of meetings with teachers to allay their fears that the students would find it difficult to develop good study habits. The teachers were also concerned it would be difficult to track pupils' progress.

During a one-month trial period in February last year, many students opted to study themselves without set homework. That paved the way for the elimination of homework altogether.

Some teachers note that because they don't need to mark and grade homework, they have more time to prepare lessons and interact with students.

Motivated to study

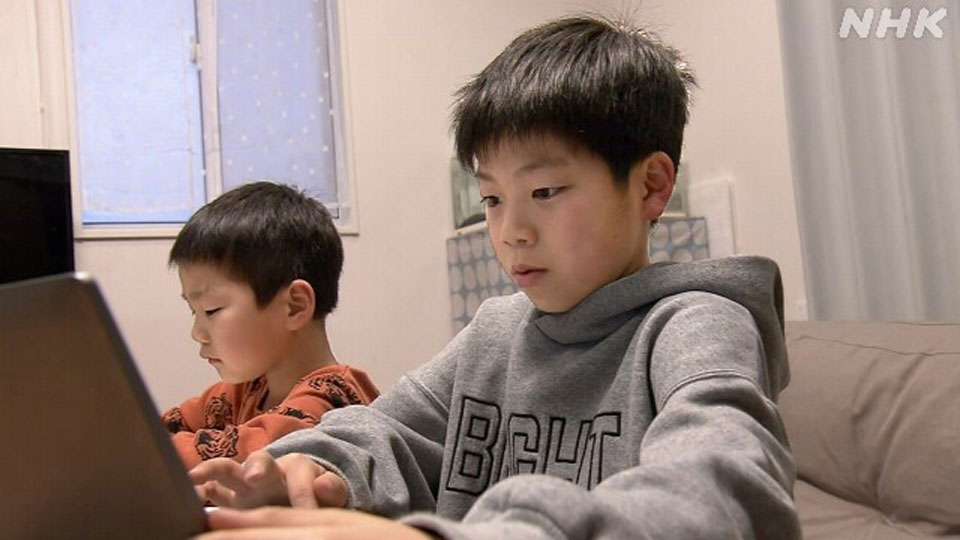

A 5th grader whom NHK chose to identify only by his first name, Ginji, still studies about twice a week after school. "I was surprised when I was told that there was no more homework, but somehow I am more motivated without it," he says.

Ginji's mother, Saori, was initially worried about the school's decision. But she sees a positive shift in her son's attitude towards study. And with no more arguments at home about homework, there is less tension and more time for listening and interaction.

Listening to parents

In a survey last July, about 10 parents at the school expressed opposition to the no-homework policy. One of the parents claimed their child had stopped studying, and another cited a decline in academic performance.

Asai addresses questions and concerns with one-on-one meetings, during which he explains the importance of independent thought and learning.

Teachers also identify students who need help with their study habits.

Educational researcher Seo Masatoshi says that kind of support is essential to ensure that no gaps appear in children's learning opportunities or academic performance.

"It's time to rethink the one-size-fits-all approach to education," he says. "But we must recognize that some children may not know how to study on their own at home, so it is necessary to help with this to some extent. During the holidays, it would be a good idea for teachers to set up an opportunity to check their students' learning progress."

In January this year, students at the school took a scholastic aptitude test. The overall results were little different to previous years, when set homework was in force.

"I believe the future is not an era of one-way cramming of knowledge," the principal says. "I want to change the way of thinking about education and academic achievement," says Asai. "There are many things we can review in Japanese schools…to help children think and act spontaneously."