Sudan and the Tottori Sand Dunes

Izzat Tahir moved to Japan's Tottori Prefecture in autumn 2022 to join Tottori University's Arid Land Research Center as a visiting professor.

His research focuses on developing new wheat varieties, a critical issue for his mother country, where the extreme temperatures and arid climate make it hard to grow essential crops. He has three decades of experience in agricultural science.

For the past five years, the research center, located right next to the Tottori sand dunes, has been conducting a project with a Sudanese national research institute to develop wheat that can withstand the harsh conditions of Sudan.

Humanitarian crisis in Sudan

Tahir, who leads the Sudanese side of the project, was planning to return home as soon as the situation improved, but he says this is impossible as long as the armed clashes between the military and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) continue.

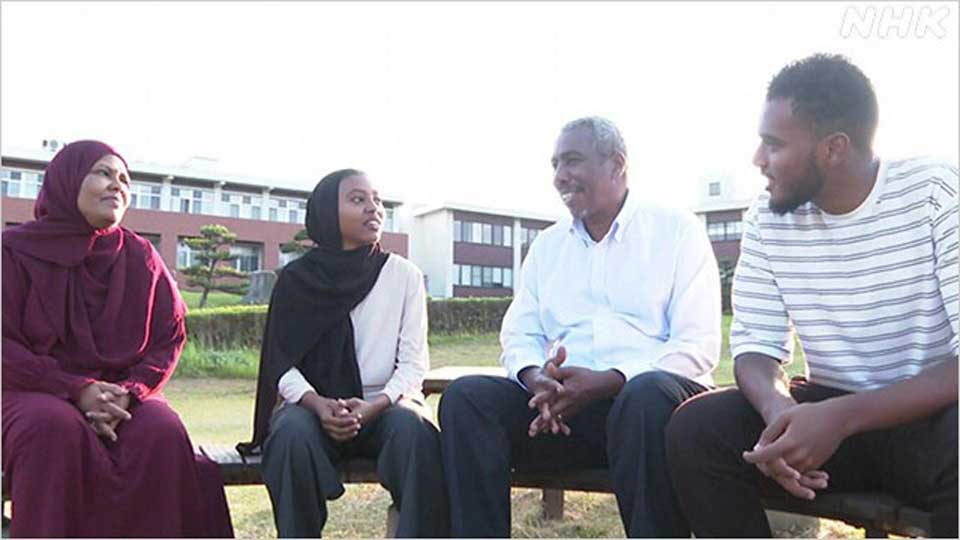

The fighting began last April, and a month later Tahir flew his wife and two children to the safety of Japan. Since then they have watched from afar as the situation unraveled.

More than 8.7 million people have fled their homes. Half of the population is in need of humanitarian assistance.

In December, Tahir learned his home in Sudan had been looted. Some of his relatives have been forced to flee, taking refuge elsewhere in the country or going abroad.

"I have not had a single day of rest in the past year," says Tahir. "It is difficult to keep in touch with my family in Sudan. People from the same country are hurting each other and destroying it with their own hands."

Family fears

Tahir's biggest concern right now is what lies ahead for his two children. They were both attending university in Sudan.

His son, Ahmed, 21, was studying urban engineering in the capital Khartoum. If everything had gone to plan he would be about to graduate, but with the coronavirus pandemic, armed clashes, and a move to Japan, he has barely attended any classes.

Ahmed's sister Aaya, 20, was enrolled in medical school and wants to become a doctor.

In Japan, they are helping with a research project between Sudan and Tottori University, studying Japanese, and taking some online courses.

"I enjoy studying Japanese language and culture," says Aaya. "But in my heart, I feel sadness that I have lost my daily life where I had friends and family around me and was able to learn."

Tahir's tenure at Tottori University will end in September. "We are praying the current situation will be settled and I can return home," he says. "This is our dream. But if not, I don't know what we will do. As a father, I am worried for my children. It is really sad that the futures of our children and young people are being destroyed."

Research affects Sudanese people's lives

In Sudan, fighting has spread to the area where the research center is located.

The Sudanese researchers who worked there have fled to other locations and it is unknown what has happened to the center itself.

In Tottori, meanwhile, Tahir and a group of Sudanese student researchers are making new plans. The university has allowed some of them to continue their work there, with support from the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). At the same time, they are looking for employment in Japan or opportunities elsewhere. For now, going home isn't an option.

Tahir is worried that any interruption to their project could have profound consequences for wheat cultivation in Sudan, exacerbating food insecurity.

"The Sudanese students studying in Japan were supposed to return home and play a role in the future of wheat research in Sudan," says Tahir. "Food is the most important thing for people to live on. If our present activities do not proceed as planned, the lives of the Sudanese people will be directly affected. I still hope the situation will improve and they will be able to return to Sudan to continue their work."

Tahir and project leader Tsujimoto Hisashi, a professor emeritus at Tottori University, are doing all they can to ensure the project continues.

They hold weekly online meetings with researchers in Sudan to share information on the local situation and determine the direction of their work.

They are also seeking further cooperation from JICA and other organizations that have supported the project so far.

"The people who are coming to Tottori University are the kind of people who will become leaders in agricultural production in Sudan in the future," says Tsujimoto. "When Sudan is in a very difficult situation, Japan wants to do everything we can to help. I think it is important not to extinguish the sparks between Sudan and Japan."

Amidst the rolling sands of the Tottori dunes, Izzat Tahir and his fellow researchers have found both refuge and purpose. They are determined to continue the work that could bring much-needed food security to their arid homeland ― despite the shadow of uncertainty that hangs over their lives.