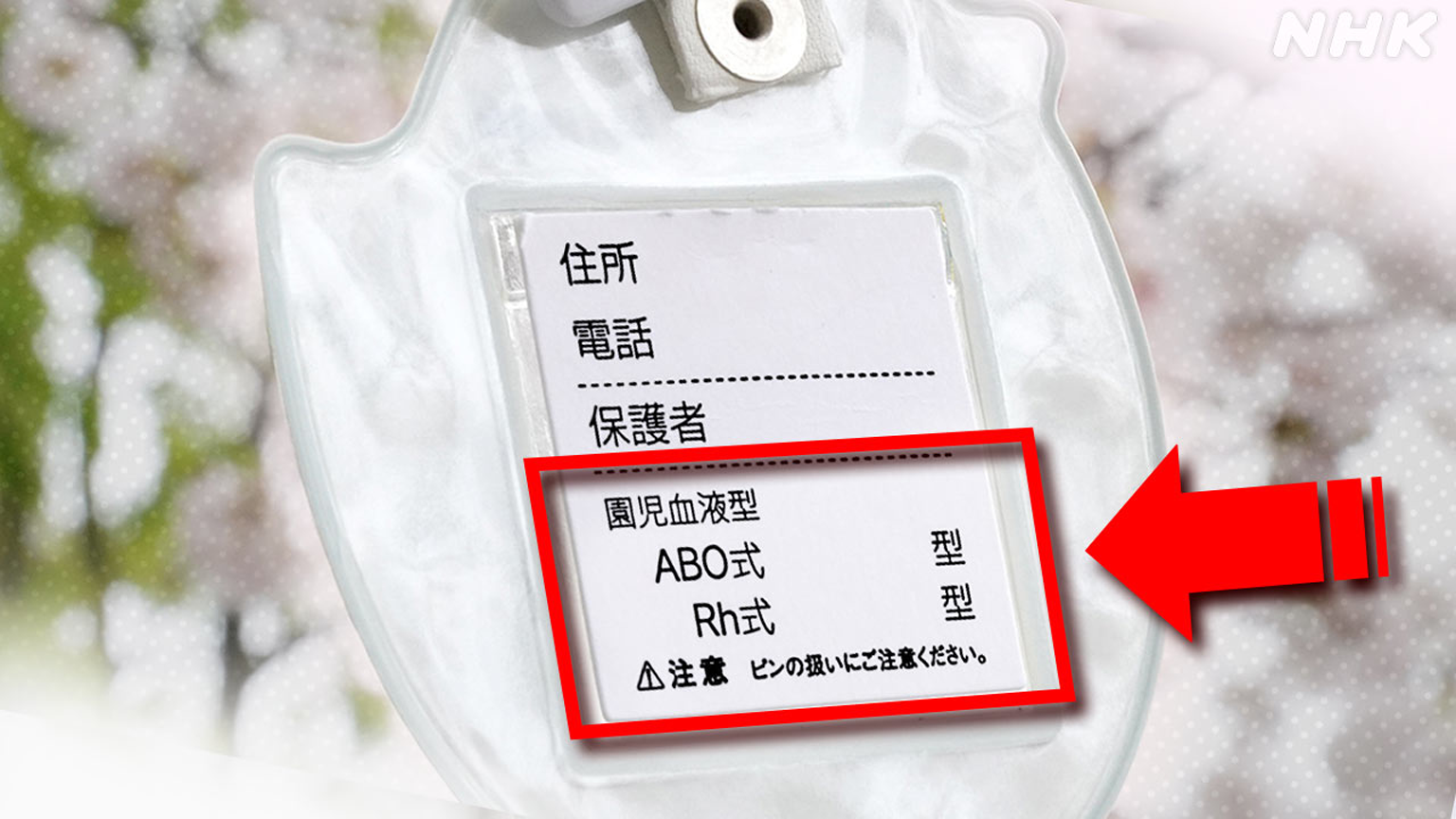

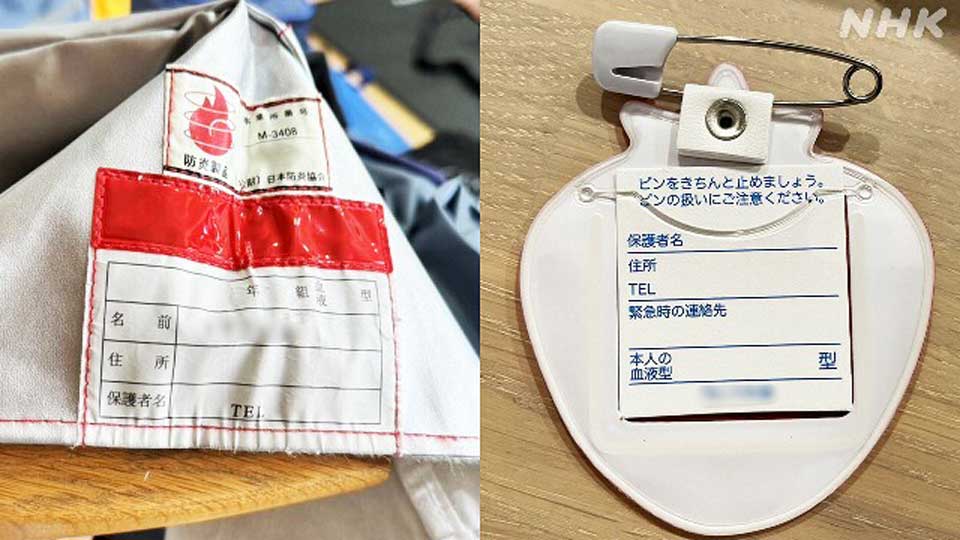

For years, children at kindergartens and schools have had their blood type recorded on name tags, protective equipment, and official documents. But that's no longer common practice.

During April, NHK World surveyed parents in Tokyo's Shibuya district to find out if they knew their children's blood type. Out of 30 children, only 12 had been tested.

"I know my oldest kid's blood type, but not the younger one," said a mother of a 13-year-old and a one-year-old. Another woman said her family doctor had told her that babies did not need to be tested.

Most of the parents who didn't know their children's blood type had no desire to find out.

Blood test protocols

"Some parents tell me that they want to know their child's blood type, but if I explain that it costs money, most of them change their mind," says Kabe Kazuhiko, Specially Appointed Professor at Saitama Medical University, who has been examining newborns for four decades.

According to Kabe, until the 1990s, many Japanese hospitals offered free testing for newborns' blood type according to the four groups: A, B, O, and AB.

Blood tests for babies have been occasionally inaccurate, leading to social problems down the road. Kabe notes that most hospitals have abandoned testing over the past two decades.

No need for tests

Although some nursery schools, kindergartens, and elementary schools require parents to provide their children's blood type, pediatric doctor Takada Yoshinobu says there is no need.

"Whenever you need a blood transfusion, medical staff perform a detailed blood test before the procedure. It's safe to say that they only believe the results of their own tests," Takada explains.

"Medical staff will always need to confirm a patient's blood type. So they'll never do the procedure based on a family member's account, or the blood type written on a name tag. That's of no use to the medical profession."

Until a few years ago, Takada was frequently asked by parents if they should have their kids' blood tested prior to enrollment in preschools or kindergartens. He convinced officials in Ikoma City, Nara Prefecture, to drop the requirement.

Aichi Prefecture's Tokai City has also made a similar decision for enrollment procedures.

"Most of the children do not know their blood type anyway," says a city official. "We don't want parents thinking they need to get their child tested for our documents."

Takada notes that blood type is personal information that does not need to be shared.

Kabe agrees: "Even if your blood type is written on your name tag or on a document, it is not medically useful," he says. "You can simply leave that section blank if you don't want to share."

While it used to be common practice to record children's blood type, Kabe says what we are seeing now shows that "things that are taken for granted can change after some time."

How to find out

For people who are still keen to discover their blood type, testing is available, but it is not covered by public health insurance. While the cost varies, in most cases, it is around 3,000-5,000 yen ($20-$30).

Blood donors can find out for free should they wish with the Japanese Red Cross Society.