The scenario is from the Population Strategy Council, a private study panel headed by Mimura Akio, a former head of the Japan Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

He fears that Japan's ongoing population decline could eventually plunge the economy into "a shrinking spiral." "We would continue to lose national wealth, and the sustainability of our social security system would be significantly undermined," Mimura says.

"What's more, Japan's global status would decline too. We should not leave behind a future like this to the coming generation. It's our responsibility."

Change or face extinction

A projection the council released a decade ago caused serious concern when it concluded that roughly half of Japan's municipalities face extinction.

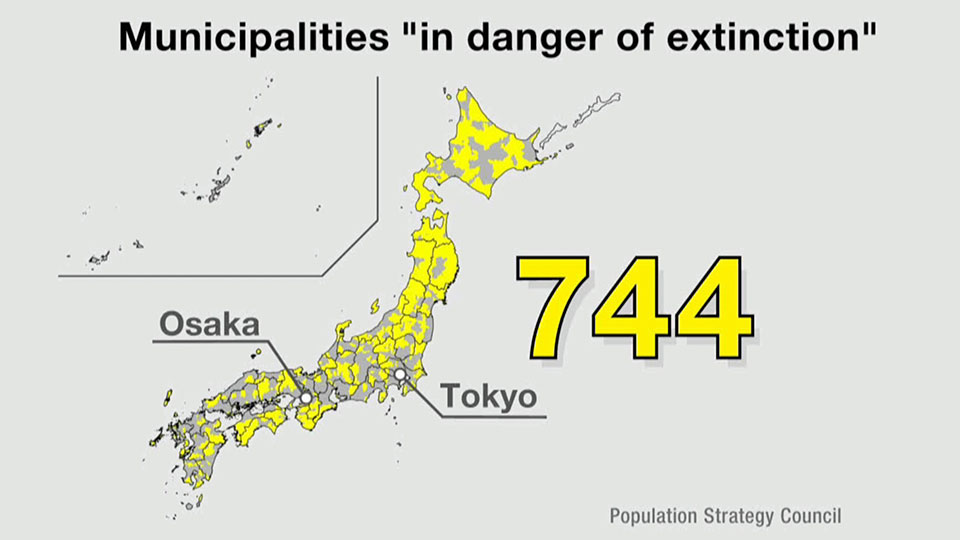

The group's latest report analyzes the numbers of women in their 20s and 30s living in each of the more than 1,700 municipalities in Japan.

It concludes that 744 of them are at risk of disappearing one day, as their populations of child-bearing age women are on track to fall to less than half of current numbers by 2050. The trend could trigger a wider population drop in those communities — to the point they no longer exist.

Communities fight back against depopulation

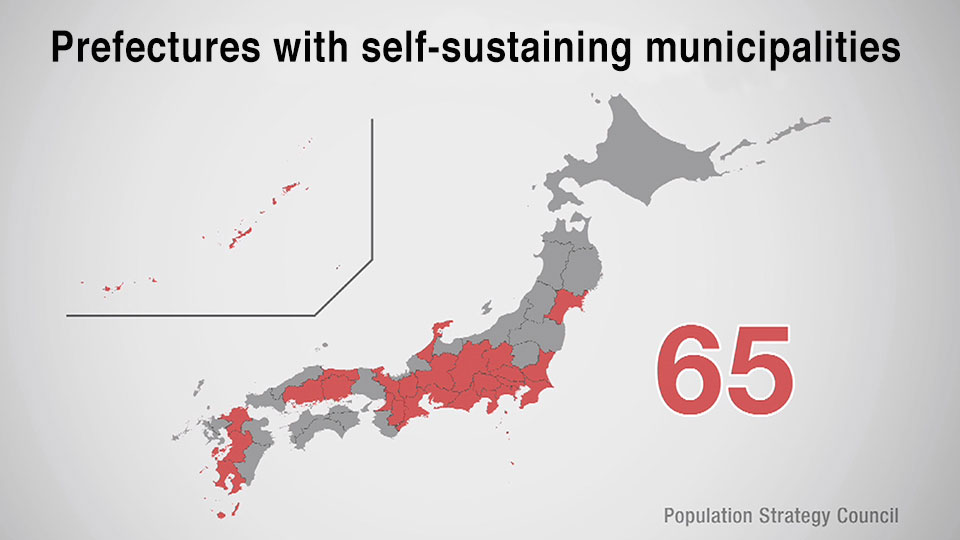

On the bright side, the number of such areas is about 150 fewer than in the previous report — highlighting how some communities are managing to turn themselves around.

Nagashima is a fishing town known for its locally farmed yellow tail. There's no high school there. Most local teenagers have to leave and many do not return.

To lure them back, the town started its "Yellow Tail student loan," named after the fish known for its long migrations. If young people borrow money to fund their studies while away, the town will later reimburse them if they return to live in Nagashima within 10 years of graduating.

To date, 376 people have used the program, and 51 percent of the ones aged over 22 have returned.

The Population Strategy Council designates 65 of Japan's municipalities as "self-sustaining." In short, their populations of young women are expected to fall by no more than about 50 percent a century from now.

Ohira Village was once deemed at risk of disappearing. But then local officials set up a team that addresses child-rearing issues.

Its incentive measures include handing out coupons for diapers and powdered milk. Some parents say the program is making a difference. "The support is really helpful," a mother of seven says. "If I had lived in a different town, I wouldn't have been able to raise my kids."

Residential areas in Ohira Village are expanding, and young families are moving in. Growing communities tend to attract businesses.

"We want to carry on creating a cycle in which people who were children raise their own right here in Ohira," the village chief says.

Nation's shrinking population is the issue

But a member of the Population Strategy Council says such successful community-level cases will not be enough to fix the overall problem of Japan's shrinking population.

Masuda Hiroya, a former internal affairs minister who oversaw the council's last two reports, says while many municipalities worked hard to attract people, "they are simply taking people away from other areas."

"Black hole" communities

The latest analysis also points to a new phenomenon dubbed "black holes." These are mostly big city areas including central Tokyo, along with Kyoto and Osaka — areas that suck in young people but have extremely low birthrates.

For example, this couple moved to Tokyo from rural Japan. They say they want to have a child but can't because of the city's high cost of living. They thought of moving to a different area but haven't been able to find jobs to their liking.

Masuda says the issue encompasses various levels of society, including programs provided by employers and community efforts to make child-raising easier. He says little will change unless politicians lay out long-term visions for the country and for local communities, and then encourage people to work toward those goals.

"Now is our last chance," Masuda says.

Japan's top government spokesperson Hayashi Yoshimasa has said it will strive to revitalize regions by encouraging young people to move there.

Population crisis: 'Disappearing' Japan

Video 8:29