Encountering E.R. Scidmore

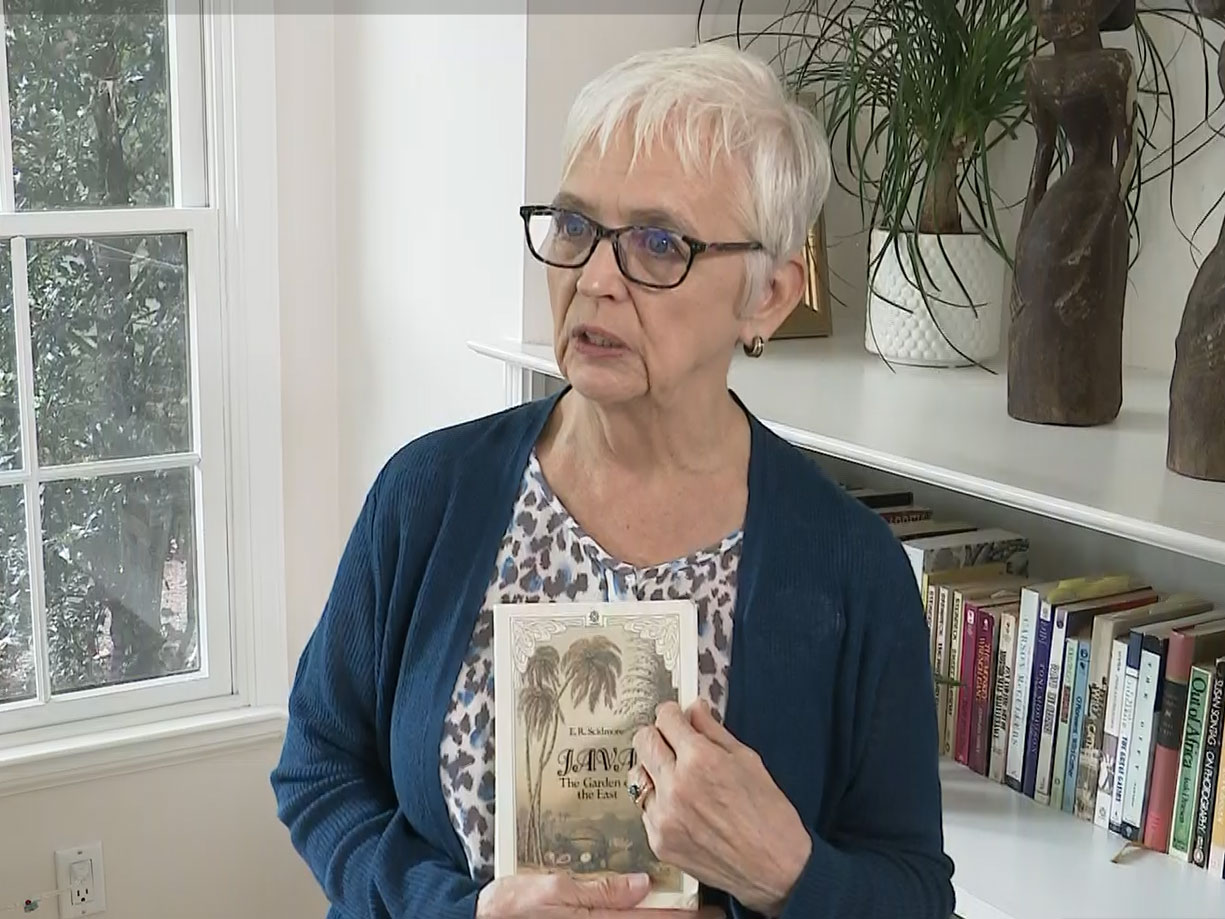

Virginia-based writer Diana Parsell recalls the day she stumbled across a 19th-century travel book, "Java: the Garden of the East" by E.R. Scidmore in a Jakarta bookstore. But it wasn't until years later that Parsell learned Scidmore was a woman.

"I was astounded to find out that Eliza Ruhmah Scidmore was a globetrotting journalist," she says.

Parsell spent the following 10 years digging further into Scidmore's life and eventually wrote the first biography of the audacious journalist. She discovered that Scidmore was widely published in newspapers and magazines, and was the National Geographic Society's first female board member. She was also the person who proposed bringing the cherry trees from Japan to her homeland's capital.

Trailblazing travel writer loved Japan

Eliza Scidmore was born in Clinton, Iowa in 1856. She started her career as a society reporter in Washington, but soon ventured out to see the wider world. Her first destination was Alaska, where her travel guide published in 1885 heralded a new era of tourism. As a show of gratitude, Alaska named a glacier and a bay in her honor.

Scidmore was next off to Japan, traveling with her mother to see her diplomat brother George, who was stationed there.

"Everything about the country fascinated her," says Parsell.

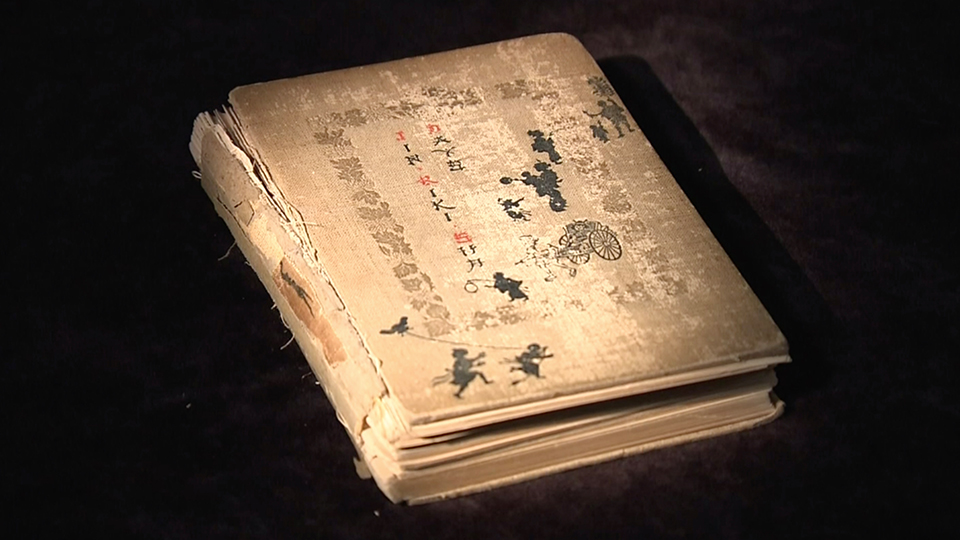

Japan had only opened its doors to the world a few decades earlier. Cars were still a rare sight, so Scidmore traveled the country by jinrikisha, or rickshaw — carts pulled by men.

Her account of the visit, "Jinrikisha Days in Japan," was published in 1891 and quickly captured the hearts of American readers. Scidmore wrote about Japan's love of hanami, an expression that translates as "flower viewing" but is used specifically for sakura, or cherry blossoms. She described how men and women, young and old, rich and poor, came together under the trees to celebrate the arrival of spring.

It wasn't just the beautiful flowers that Scidmore wanted to take back to Washington, Parsell says, but the hanami culture too.

Long road to success

In the late 19th century, Washington was undergoing major development. The Army Corps of Engineers created the Tidal Basin to control the Potomac River's flow and prevent flooding. Scidmore proposed that the city plant cherry trees around the Basin, but officials did not see the appeal.

It took Scidmore another two decades of tireless lobbying to achieve a breakthrough. In 1909, her friend Helen Taft became First Lady when her husband William Taft was elected president.

Helen, who was tasked with beautifying the area around the Basin, had also lived in Japan and knew about hanami culture. By then, Scidmore was a celebrity in diplomatic circles and enjoyed strong support from high-profile Japanese friends. Among them was Takamine Jokichi, a biochemist and industrial leader who successfully isolated the chemical adrenalin. Takamine offered to cover much of the project's cost.

In 1910, the first batch of 2,000 trees arrived as a gift from the mayor of Tokyo, Ozaki Yukio, to the people of the United States. Unfortunately, inspectors found some of the trees were infested with insects and ordered the entire batch to be destroyed.

But the Japanese side did not give up. Two years later, they sent another batch of 3,000 trees. The first two were planted by First Lady Helen Taft and the wife of the Japanese Ambassador, Chinda Iha. Scidmore was also at the ceremony to see her efforts finally come to fruition.

From fame to obscurity — and back

Washington's cherry trees are now a famous symbol of the friendship between Japan and the United States. But the person largely responsible for getting them there soon faded into obscurity, becoming little more than a footnote in the story.

Scidmore spent her last years in Geneva, dying there alone in 1928 at the age of 72. Her mother and brother had both died in Japan and were buried in Yokohama, so Scidmore's diplomat friends arranged with the Japanese government to transport her ashes there to be reunited with her family.

Nearly 100 years later, a small group of people carry on an annual tradition to honor her legacy. Every year on November 3, the anniversary of Scidmore's death, they gather at her grave in the Yokohama Foreign General Cemetery to lay flowers.

The group is now led by Umemoto Chiaki, who says Scidmore remains a recognized figure in the Yokohama area. She says when she was young, her mother would tell her about the Potomac cherry trees.

"When I moved to the US for my husband's work, I was shocked that none of the Americans I talked to knew about her," she says.

Umemoto was determined to change that, so she started visiting schools to tell American children the story. Upon her return to Japan in 2020, she took up the leadership role of the local citizens' group that honors Scidmore's legacy.

Scidmore Sakura

In 1991, Washington gave Japan some offspring of the Potomac cherry trees. One of them now stands in front of Scidmore's grave and continues to blossom every year.

Umemoto calls it the Scidmore Sakura. Her group propagates cuttings from the tree through grafting with help from Yokohama Nursery, the company that sent the original 3,000 healthy trees to Washington in 1912. The group eventually plants the saplings at schools and other sites in the area.

Last year, group members ran a workshop at a Yokohama elementary school, to teach children about the history of the Potomac cherry trees and show them the grafting technique. This March, they planted two of the saplings in the school yard.

"These trees will remind me of Scidmore and the cherry tree story," said a 12-year-old girl. "I'll come back to watch them grow even after I graduate."