Uncertain about prospects for rebuilding their lives

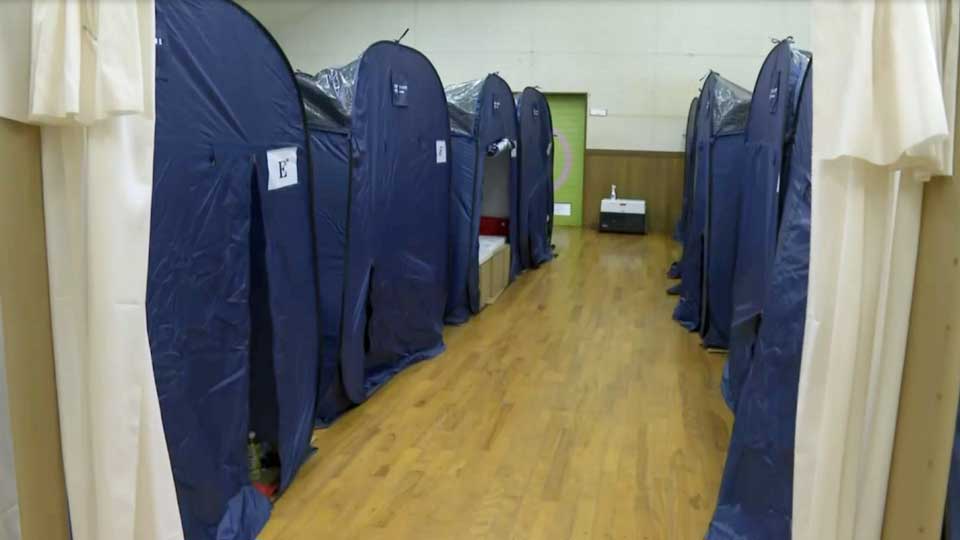

The earthquake initially displaced about 33,500 people in Ishikawa who fled to 371 primary evacuation shelters. The number gradually decreased as people moved to other places. Three months after the disaster, 142 shelters still housed about 3,300 evacuees.

Wajima City's 154 shelters accepted 12,900 evacuees, but their number had fallen to 1,364 evacuees in 49 shelters as of April 9. On that date, Suzu City had 894 evacuees in 35 shelters, down from 7,668 people in 93 shelters in January.

Many of those who remain in shelters are still waiting to move into temporary housing, while others hope to repair their quake-damaged homes. They say their uncertainty is rising about the prospects for rebuilding their lives. They are also concerned that some municipalities stopped sending staff to shelters at the end of March, making continuous support a challenge.

Soup service ends for some Suzu City evacuees

About 600 people between the ages of 1 and 90 were still living in an evacuation shelter in Suzu City's Iida Town as of April 9, almost unchanged from January. Many of them have not been able to move into temporary housing, and others must remain in the shelter due to delays in restoring the local water supply.

Volunteers had been preparing soup in the shelter through March, but the service almost completely disappeared in April. Evacuees must now make do with relief supplies such as instant noodles and packaged rice.

Suzu City had accepted help from other local governments outside the prefecture who dispatched staff to help run the shelter until last month.

An electrician in his 30s who lives in the shelter said, "I can't even get into temporary housing, so I have nowhere to go. I can't make a living without supplies and other support, so I want the support to be reduced as little as possible."

Progress has a downside in Wajima City

About 50 people were living in a shelter in Wajima City's Monzen Town as of April 9. Temporary housing was completed nearby at the end of March, and some people will start moving in. But this progress has a downside for the evacuees who remain.

The shelter is managed not only by volunteers but also by evacuees themselves, and some fear the shelter's operations will falter as people leave.

"I myself am worried about what will happen in the future, because if I move into temporary housing and resume work, my activities at the shelter will be cut off halfway through," said Shibata Sumika, an evacuee who has helped run the shelter.

"There are many elderly people who cannot go shopping by themselves, and they need soup kitchens, so I would be grateful if people could continue to support them," she said.

Wajima City officials, shelter managers meet

Managers of 15 evacuation shelters in Wajima City met with local officials on April 9. The meeting was the first of its kind, to discuss shelter management and support for those who have no choice but to remain while temporary housing is constructed.

"Temporary housing will be ready in April and May, and many people are expected to leave shelters, but shelters will still be needed after that," a city official said at the beginning of the meeting.

"We want to ask evacuees to cooperate with the self-management of shelters to some extent, but circumstances differ from place to place, so we want to discuss this."

The meeting was closed to the public. According to the city government, evacuees asked authorities to show prospects for rebuilding their lives, including the construction of temporary housing and the restoration of the water supply.

Hiratani Kenichi, director of the Lifelong Learning Division of the Wajima City Board of Education, said, "From now on, we want to discuss the living environment at the evacuation shelters in more detail."

Furutani Yutaka, who is in charge of shelter operations, appreciated being able to participate in the meeting.

"I am glad because we did not have a chance to exchange opinions as a whole until now," he said. "Information such as where and how many temporary housing units are going to be built in the future will be a great source of energizy for evacuees."

Similar meetings will be held weekly to discuss issues related to shelter management and coordinate countermeasures.