It was a cold, rainy February morning. The Tokyo Electric Power Company, or TEPCO, had agreed to let us inside Fukushima Daiichi – but just getting there is a challenge. Only authorized vehicles are allowed to get close, so we waited outside for a bus sent by TEPCO.

Nobody can access the area around the plant without permission. We drove past old, empty houses — places that used to be people's homes. Residents near the plant were forced to evacuate after the accident. Tall grass sprouts over the abandoned sidewalks.

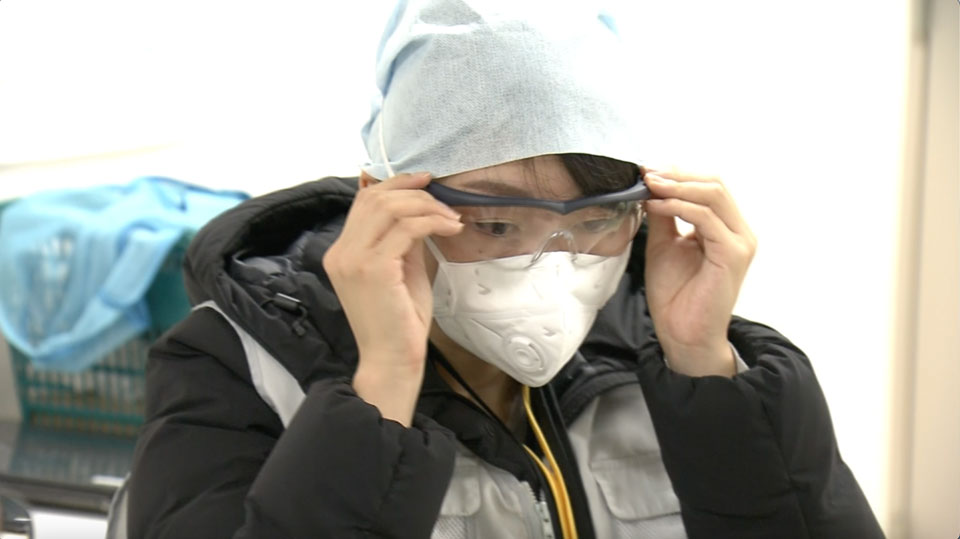

Inside the plant, we had to pass strict security checks. Then, we put on our protective gear: a helmet, a mask, glasses, gloves, a vest, followed by two layers of socks. Finally, we received our dosimeters: small devices to measure our radiation exposure. We had to wear them at all times.

I was surprised to see workers wearing the same basic protective gear that we were. I later learned that only people working near the plant need full-body suits. That's because the monitoring posts around the facility all show that radiation levels have been going down over the years.

With our gear on, we made our way to the tour — the No.1 reactor.

No.1 reactor

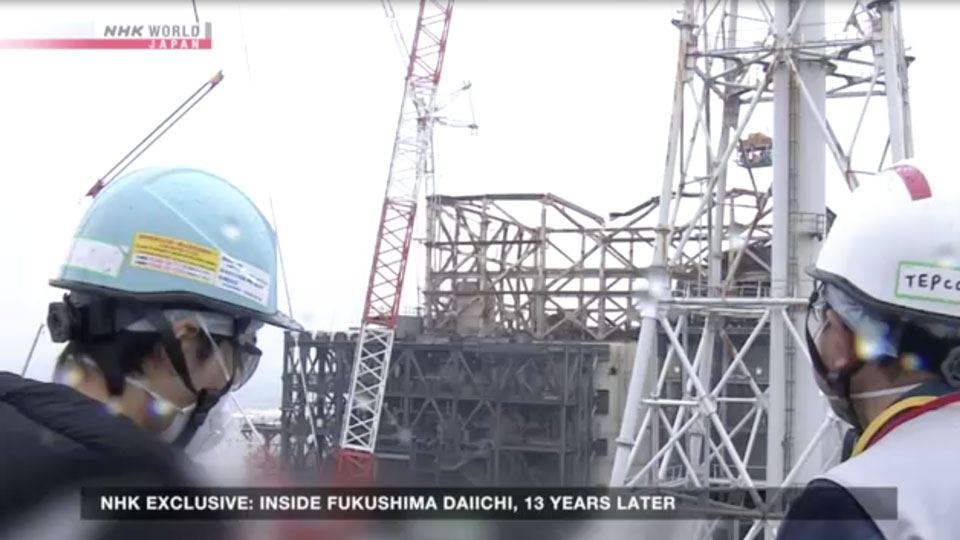

You need only look at the No.1 reactor to see what went wrong. The building was severely damaged by a hydrogen explosion. Even now, there's twisted metal and debris scattered where the roof used to be. I was surprised by how much was still left there, 13 years after the disaster.

After we arrived, our dosimeters began going off, warning us about the radiation. It was still within acceptable levels, but as a precautionary measure TEPCO officials quickly ushered us away from certain spots, even though we wanted to stay a little longer.

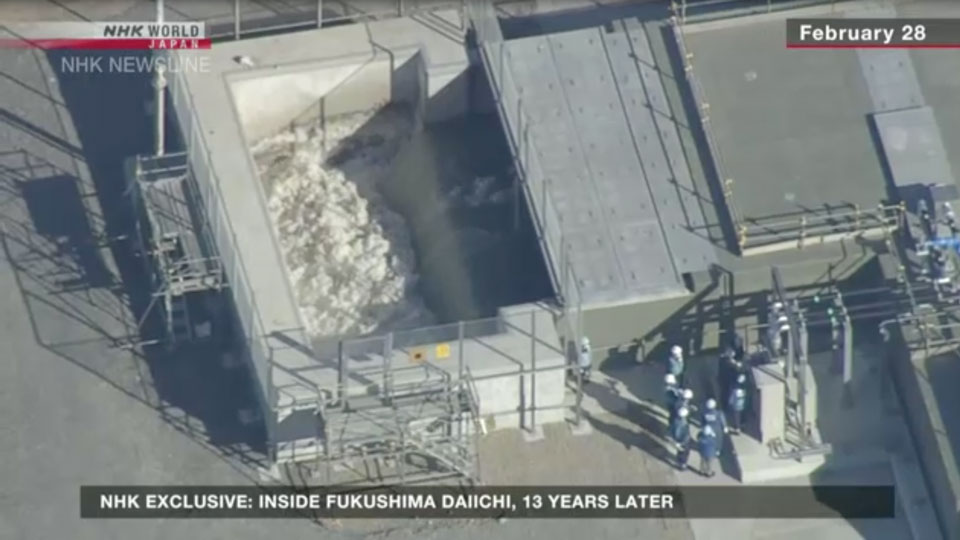

Almost 400 unused and spent nuclear fuel units are still inside, in a pool of water on the top floor. TEPCO will have to sift through layers of debris to get to them. But first, they plan to build a cover that will contain any radioactive substances, like dust.

Right now, they're still building the frame for the cover. The finished structure is expected to be 65 meters tall.

No.2 reactor

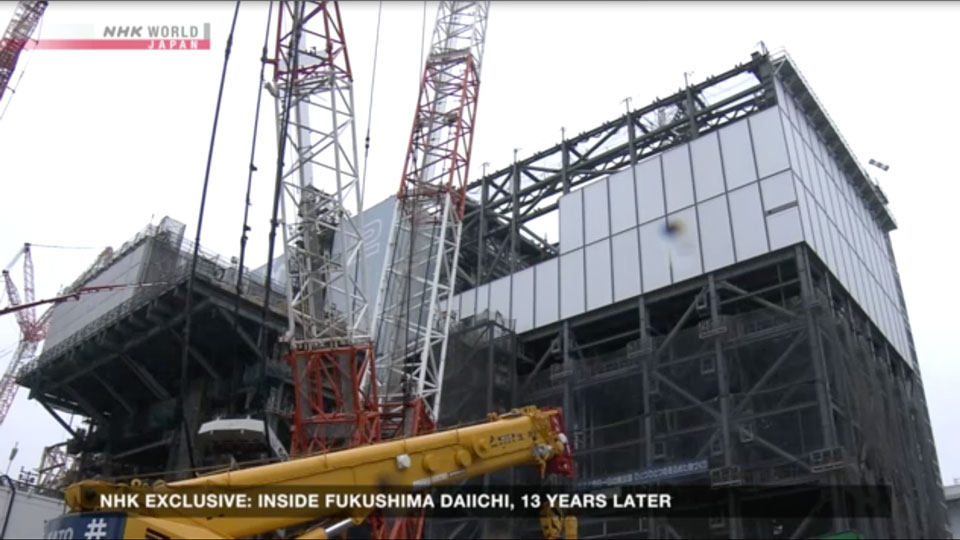

Just next door is the No.2 reactor. It has a similar problem: unused and spent nuclear fuel units need to be removed. There are 615 units lying in a pool of water. A large, white building houses some of the equipment they'll need for the extraction.

But there is a much bigger hurdle. Fuel debris, which is a mixture of molten fuel and surrounding devices from the reactor itself, also has to be taken out. But the radiation is so high, humans can’t get close. TEPCO plans to deploy robots to try to remove the debris. It was supposed to hold a trial run three years ago. That was recently delayed for a third time and is currently slated for this autumn.

The real challenge will be the removal of a combined total of more than 800 tons of fuel debris from the No. 1, 2 and 3 reactors.

Traces of the tsunami

The reactors weren't the only things damaged by the tsunami. The plant was built above sea level, but the tsunami still swept through the facility, causing widespread destruction.

A dark line marks the tsunami's water level, five meters above the ground. TEPCO has placed a sign on a building, so everyone can see how high the waters reached. Equipment was also destroyed: we saw water tanks crumpled like balls of paper from the force of the tsunami.

New construction and old, decrepit buildings stand side-by-side.

Dealing with the water

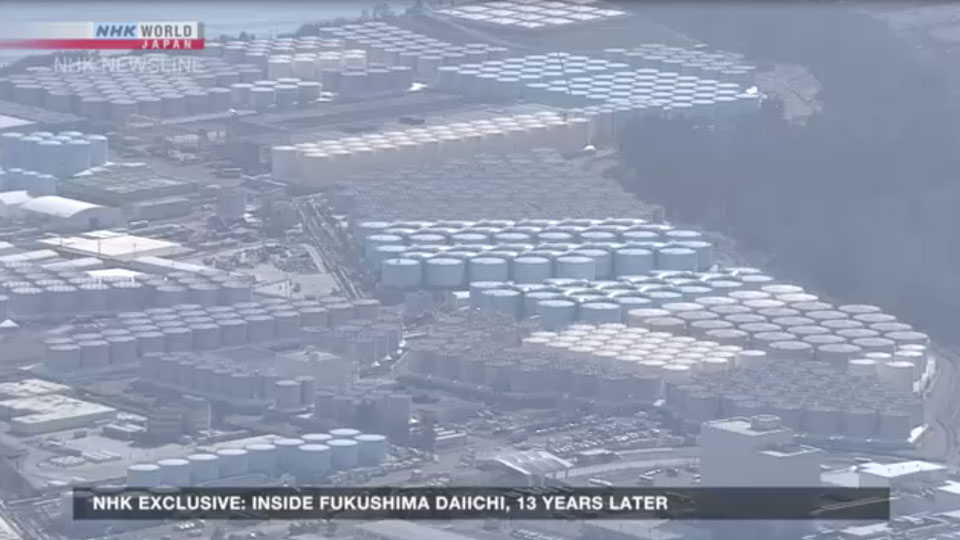

Today, the biggest problem facing the plant is a logistical one. TEPCO needs somewhere to safely store radioactive waste, including fuel debris. But right now, water from the reactors is taking up precious space.

Since the accident, TEPCO has been pumping water into the reactors to cool molten fuel. But rain and groundwater is also seeping in. The operator treats the water to remove most of the radioactive substances, but it still contains tritium.

The treated water is stored in more than 1,000 on-site tanks, each of which stand about 15 meters tall. Together, they can hold over 1.3 million tons of water, but TEPCO is approaching that limit with more than 90 percent of the tanks already full.

That's why TEPCO has moved to release the water, after diluting it with sea water to reduce the tritium levels to about one-seventh of the World Health Organization's guidance level for drinking water.

The fourth round of the water release finished in March. Samples from the process show there are up to 16 becquerels of tritium per liter of sea water. TEPCO previously said it would stop the release if the concentration went above 700 becquerels.

The International Atomic Energy Agency's task force reviewing the discharge issued a report in January. It reaffirmed that Japan's discharge of treated and diluted water from the plant is consistent with international safety standards.

TEPCO plans to release more than 54,000 tons of the water in seven rounds over the current fiscal year.

People told me the area can't fully recover until the plant is decommissioned. Nearby residents had to flee when the accident happened and not everyone can come back yet. Thirteen years have passed since the disaster and the situation in the area is improving, but there are still many issues to resolve.