Back in Ukraine after five years

My name is Kateryna Novytska. I am 28 and my hobby is cosplay. I’ve loved Japanese anime since I first saw "Sailor Moon" as a child.

I came to Japan five years ago and started working at NHK. I have been producing reports mainly on Japanese subculture.

On February 24, 2022, Russia invaded my country. My life and that of my family changed forever. My younger sister evacuated to Japan, while my parents chose to remain in Kyiv. They have been living with missile attacks for two years now.

I have stayed in Japan to deliver Ukrainian voices to Japanese people. I believe this is my mission. But there's been a thought at the back of my head for the past two years.

"I haven't spent even a minute in wartime Ukraine. I haven't witnessed the horror. But I talk about the invasion and the people. I want to be there with them, feel their presence. I want to be confident in the stories I convey."

I decided to go back to Ukraine for about a month last fall. I was accompanied by a Japanese director and cameraperson.

To be honest, I was more excited than scared. Thus began my journey to find out how the war has changed my home, and will change me.

Journey to Kyiv

Air routes over Ukraine are currently suspended, so the only way to travel is by land. Getting to Kyiv took me three times longer than usual. After flying from Japan to Poland, I had to cross the Ukrainian border on foot. Then I took a night train from the western city of Lviv to Kyiv.

The first thing I noticed when I arrived in Ukraine was the evacuees. Before the invasion, Lviv's city station would always be bustling with tourists. Now, it's filled with displaced mothers and their children.

I saw a little girl on the platform holding a big toy horse. I started talking to her mother.

Mother: My daughter and I are staying in the Czech Republic and now we're returning home for just two weeks to see her dad. As for the evacuation, I told my daughter: "This is a girl's adventure. Only girls travel, boys stay and protect our country and home."

Me: What does peace mean to you?

Mother: I think peace means being able to put my daughter to sleep without having to worry about where her belongings, shoes, and water are, so we can quickly escape.

On the night train to Kyiv, I met a family who have lived away from their home. They come from the city of Avdiivka, which has become a raging battlefield.

Husband: I have heard there are up to 600 rounds of shelling every day in my hometown. There is no fire extinguishing equipment and no firefighters. Those who remain in the city are putting out the fires on their own and rescuing people. However, I heard there are bodies trapped under the rubble.

Wife: Today, as I was walking in the city, I felt envious of people who can sleep in their own beds and bathe in their own bathrooms. I don't know where to start rebuilding my life. I can't give up on the dream of going back to my hometown.

During those first hours back in Ukraine, I realized that in a war, everyone you meet will have unimaginable stories to tell.

Home sweet home

My father, Oleg, and mother, Nataliia, were waiting for me at Kyiv station. Our reunion felt like a miracle.

But I quickly realized that both my parents and my home had changed greatly. The entrance hall to our apartment used to be decorated with a big mirror and a painting. On my return, I was greeted with bare walls.

Russian missile and drone strikes continue in Kyiv. When there's an attack, an air raid warning is issued and a notification is sent to your smartphone. Until the warning is lifted, you have to evacuate to a safe location, like a windowless hallway.

In my childhood bedroom, which I shared with my sister, I found a calendar. The date was still February 2022. Since my sister evacuated abroad, no one has been around to turn the pages. Time stopped with the beginning of the war.

Small signs of war

As I walked around Kyiv, I saw that shops and restaurants were open and many people were hanging out with their friends and family. A city seemingly at peace. But it's different from how it was before the invasion. Military posters are everywhere and the windows of apartment buildings are taped to prevent them from breaking during explosions.

I decided to visit my old school. In Ukraine, we study in the same building, with the same classmates, for 11 years. School was like a second home for me. As I walked in, a group of children gathered around, curious about the camera.

Me: What grade are you in?

Students: We're in the 7th grade.

Me: How old are you all?

Students: 12 or 13 years old.

Me: Did the school change due to the war?

Students: Yes, all textbooks are now online.

Students: Some students have evacuated overseas.

Students: Three students from our class have evacuated overseas. They may never return.

Students: Everything is changing rapidly these days.

Students: My childhood is passing quickly and I'm getting closer to adulthood, but I have no memories because the war started.

As we said goodbye, one student bowed to us in the Japanese style. It turns out she likes anime. They all seemed so cheerful.

But on the bulletin board, I found posters I didn't see when I was in school. They were about the impact of the war on the mental health of children and how to help them.

"For those of you who can hear the air raid alert even when there isn't one."

"Tell the truth, are you okay?"

There was another big change. The school basement had been transformed into a shelter. I asked the principal to show me around.

It felt very strange to be down there. When I was in school, the basement was strictly off-limits to students. But now, whenever there's an air raid, teachers and students go down there and continue classes. Bathrooms and ventilation equipment are being installed so the basement can be used for long periods of time.

Oksana Belkina, school principal: We can shelter up to 400 students here. But the school has more than 400 students, so we can't evacuate all at once. That's why the school changed to a two-shift system. After the elementary school students finish, the students from the upper grades take their classes. At some point, we even considered installing beds here. But I still hope it's only for a short period of time and we won't have to use all these things.

On some days, the teachers and students are down there up to three times a day.

Class reunion

I graduated from the school in 2013. It was a time of peace and dreams, with no signs of war. At graduation, we parted ways, promising to meet again in 10 years.

I contacted my former classmates and we decided to meet in our old classroom, to fulfill our promise of a ten-year reunion.

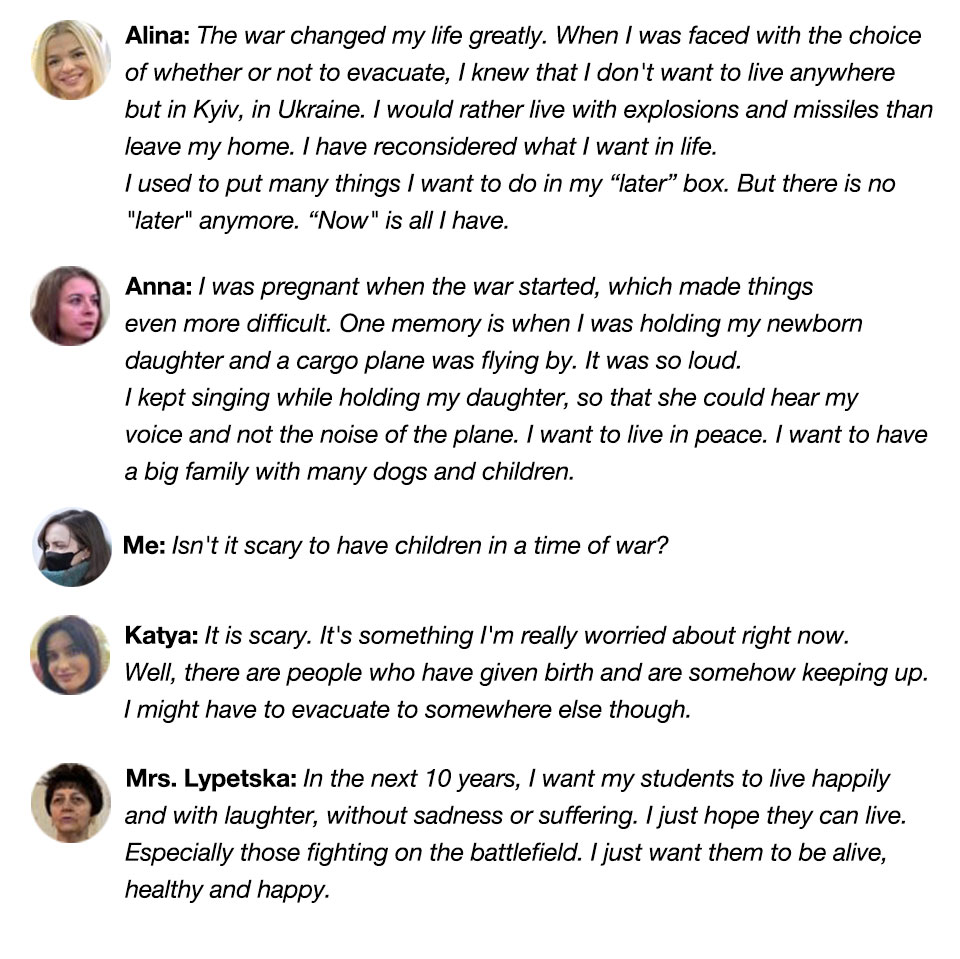

Ten of my classmates showed up. Our homeroom and biology teacher, Olha Lypetska, also joined.

It felt like we were back in school and nothing had changed. But as soon as we mentioned our old classmates on the battlefield, the room fell silent.

Andrii, always cheerful, and Yaroslav, who was the quiet one. They both volunteered as soon as the invasion began and are now fighting the Russian army.

I asked my classmates how the war has changed their values.

Hopefully we can meet up in another ten years' time.

Life for young people in Ukraine

I visited my classmate, Polina. We became friends because we both liked anime and we still keep in touch.

Polina's home is filled with anime items. But I also noticed many candles and batteries.

Me: Why do you have all this?

Polina: I have a lot of things for emergencies. For example, these stripes, which reflect light are a necessity. I often wear black clothes, but when we had power outages, there were more traffic accidents because there were no street lights. That's why I started wearing these reflectors.

Also, a radio. It was very difficult to obtain. People rushed to buy radios, and the prices skyrocketed. If there's an outage, since there's no internet connection, radio is the only way to get accurate information. For example, if there is a nuclear attack, you only have 10 minutes to protect yourself. I have to run to the subway. The entrance will be closed in 10 minutes, so I need to get information as soon as possible.

I can now tell the difference between the sounds of drones and missiles. If I know the type of missile, I can tell how long it will take for it to reach here. I think all Ukrainians have become kind of experts on war. The more you know, the more secure you will feel.

Polina heard a big explosion for the first time on February 24, 2022. Afterwards, she felt helpless and couldn’t eat. Some of her hair fell out. Even now, she suffers from trauma and sometimes hears air raid sirens when there are none.

Polina says her job is what helps keep her mind at ease. She's a designer at a Ukrainian app developer. The work helps alleviate the sense of helplessness that she and many Ukrainians are struggling with.

Polina: When the war started, for the first time in my life I thought, "Ukraine not existing is possible." The only reason I can sit here now is because of those on the front lines and the support from abroad. That's why I have to do my best. I have to work, pay taxes to the country, and donate to the army. Donating has become a daily routine. When I go somewhere I donate, when I ride the subway I donate, when someone I know asks me to help, I donate.

Polina: If you show the company a screenshot of your donation to the military, the company will double it. It has been a very supportive initiative and it has now become a new standard when choosing a job in Ukraine. People don't want to work for a company that doesn't support Ukraine and doesn't donate. That's very important to me.

A shocking death

Nine days after the reunion, I received a message. My former classmate Yaroslav had been killed on the battlefield. I had just been messaging him about attending the reunion. His last message was, "I might go, but I don't know yet."

Yaroslav always sat at the back of the class. We didn't talk much, but I got the impression that he was a kind person. He walked with me at graduation.

Three days later, I went to his funeral. My classmates were there, too. Yaroslav was buried in the cemetery for soldiers. He and I had the same birthday. He died just five days after turning 28.

I contacted Yaroslav's mother. I wanted to know more about my old classmate who sat at the back of the class.

Kateryna: When did he decide to go to the front?

Mother: He volunteered without even telling me. One day, I saw him near a military facility and asked, "What are you doing here?" He had already completed the preparations and all other formalities. And he left that very night.

I couldn't get in touch with him on his birthday. I sent him a message, saying I bought a cake and ate it myself. He called me the next day to ask how it tasted.

This is hard. I still can't come to terms with his death. Even when I visit his grave, I don't think it's my son's. People praised him. He is certainly a hero. I have lived for him, but I don't know the meaning of living anymore.

Maidan Square in the center of Kyiv has become a mourning point. People bring flags bearing the names of those killed by Russia. I placed one for Yaroslav.

Before I went back to Ukraine, I thought that I needed to seek out people who have been affected by the war, to find them and tell their stories. But now I know that in reality, the war has affected every aspect of life in Ukraine. You don't have to look. It's everywhere.

People who were living happily and in peace are now deeply traumatized. But they are still trying to live, to persevere, even though they can’t be sure tomorrow will come. This is the reality of the life in Ukraine that I saw.

NHK director Nagata Ayaka

For about a month, I followed Kateryna around Ukraine, carrying a camera. Before we went, I thought I would see fierce battles, destroyed cities, death, people in grief. These are the images I have seen of Ukraine on the news over the past two years. But when I actually got there and looked around, it was very different.

In Lviv and Kyiv, I saw happy people on cafe terraces spending time with their families and friends. I saw young people smiling and taking selfies. Restaurants and shops were crowded.

But if you looked closely, you saw signs of war all around. Soldiers walking around in uniform, posters recruiting drone pilots. I even saw a destroyed tank lying in front of a beautiful church square. The war is deeply embedded in daily life and air raid sirens can start at any moment—while you are in the bathroom, for example, or having a dinner.

The war has also left many invisible scars on people's hearts. Every person I met said that war isn't just about the fighting. They told me they have found what they value most in life and that they try to live each day to the fullest.

The people I passed on the street have all survived two years of missile strikes. They're still smiling because the present moment is what they care about. Knowing this changed my perspective on what I was seeing.

This is what one of Kateryna's friends said:

"I want people to know the original Ukraine, how we used to live. I want people to see not only our 'death' and 'destruction' but also our life and that it is now threatened by war."

What I saw in Ukraine was people who want to live a simple life with their loved ones, while preserving what makes them Ukrainian.