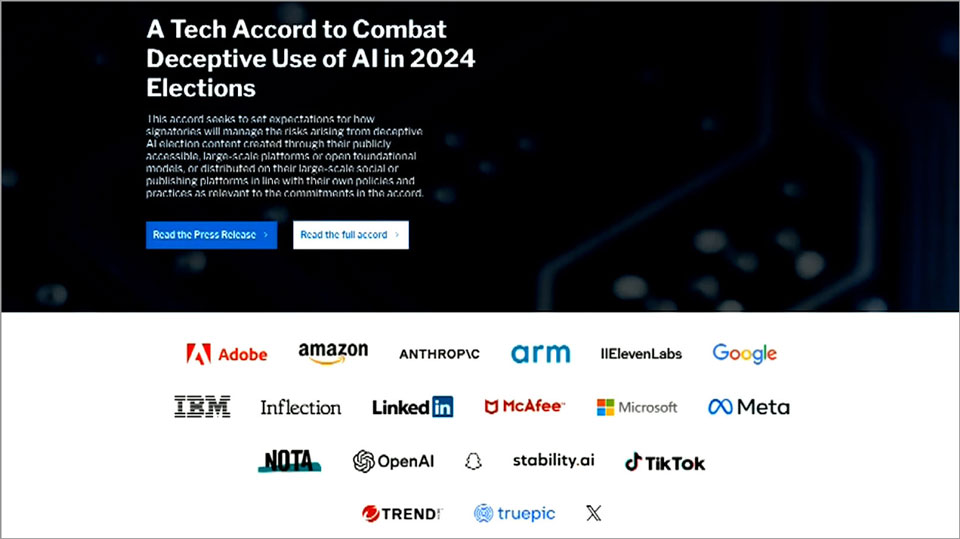

Tech giants to take action

In mid-February, 20 firms gathered at the Munich Security Conference — including OpenAI and Google — agreed to cooperate in developing technology to identify deceptive AI-generated audio, video and images.

The accord states the spread of misleading AI content could deceive the public in ways that "jeopardize the integrity of electoral processes."

The threat is real.

In January, New Hampshire residents received an AI-generated robocall imitating US President Joe Biden's voice. The message urged people not to vote in the state's January 23 presidential primary.

Fishing for votes with fake reality

More than 200 million people were eligible to vote in Indonesia's president election. A little over half — 52 percent — were 40 or younger, prompting candidates to use AI in their campaigns to grab their attention.

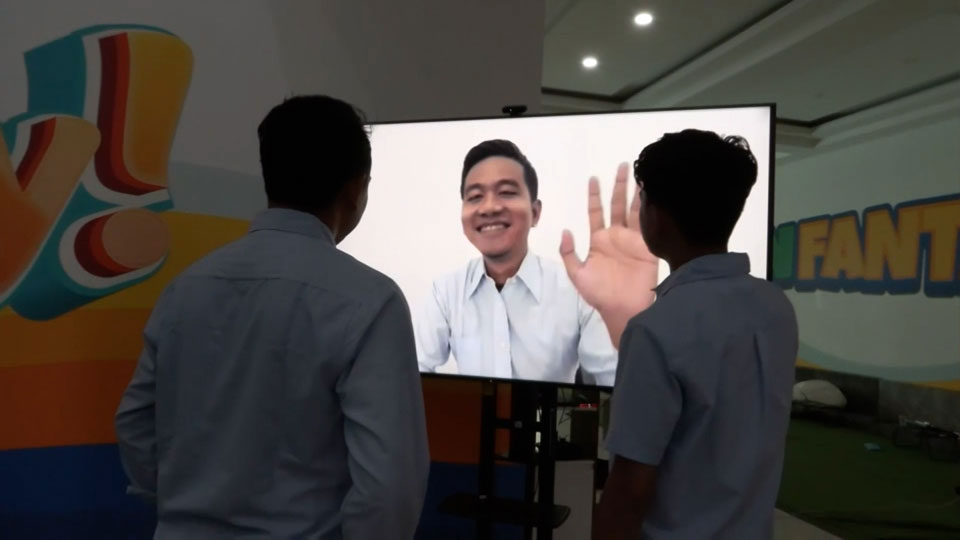

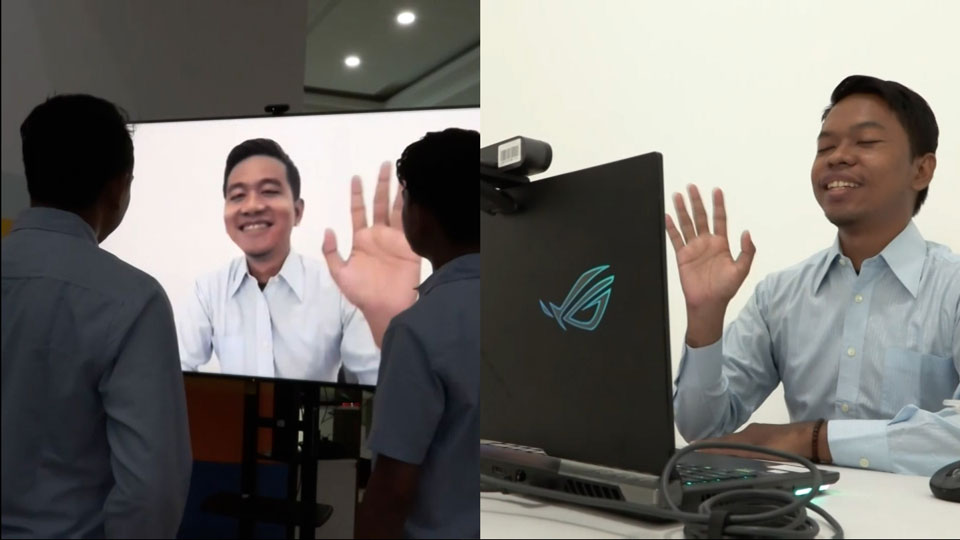

It appears as if vice presidential candidate Gibran Rakabuming Raka is talking to voters via a monitor. When a voter asks how the debate was, Gibran replies, "I was very nervous so I'm tired."

But the image of Gibran on the monitor is being generated by AI. Unknown to them, the voters are actually speaking with a campaign worker.

"Young people are attracted by candidates with new ideas. I think it's OK to use AI technology as long as it does not lead to anything bad or disseminate false information," says a Gibran campaign representative.

AI breathes new life into a political giant

The use of AI in other campaigns has also raised moral and ethical questions.

A video released one month before the election appears to show former Indonesian President Suharto — who died in 2008 — asking voters to support the Golkar Party, which he led. The video was made by a high-ranking party official who had close ties with Suharto.

The move was criticized on social media.

Another candidate released a video of himself speaking fluent Arabic. About 80 percent of Indonesians are Muslims and Arabic speakers are very much respected. But in reality this candidate doesn't know the language.

About 640 cases of fake election-related information were confirmed last year in Indonesia — five times more than in the previous 2019 election.

Indonesia currently does not ban the use of AI in political campaigns.

Election interference via AI

The role played by AI in Taiwan's recent presidential election has also raised questions.

One AI-generated video showed ruling party candidate Lai Ching-te saying his two opponents would be suitable leaders. But fact-checkers subsequently revealed it was created using footage of Lai expressing the opposite sentiment.

A Taiwanese NPO believes people used AI to interfere with the election, fuel anxiety and inflame societal divisions.

Fact-checkers search for solution

The rapid increase in AI-generated fake information poses a major challenge for fact-checkers worldwide.

About 700 people from 32 countries and regions participated in an international conference in Singapore last December to discuss countermeasures.

Fact-checkers say false information spreads faster than the truth because it's designed to garner attention and stir emotions. They believe the solution is greater engagement to improve the public's information literacy.

Japan is no exception

Furuta Daisuke, editor-in-chief of the Japan Fact-check Center, took part in the meeting. He pointed out that fake information is increasing in Japan as well, and said efforts to improve information literacy are not keeping up.

Professor Okumura Nobuyuki of Musashi University also says Japan has been slow to recognize the need to fact-check because its society is very stable. Yet, he notes fake news can have major repercussions if enough people believe it, so people need to be aware of it.