Better-equipped facilities, classified as secondary shelters, can help prevent disaster-related deaths — those brought about by factors such as worsening health after disasters rather than directly caused by the events themselves.

As of January 15, there were 14 suspected disaster-related deaths.

Living in emergency shelters is stressful and increases the risk of illness. So Ishikawa Prefecture authorities want to transfer vulnerable evacuees — the elderly, those with special needs and pregnant women — to more distant secondary shelters, such as hotels.

Most evacuees staying put

Prefectural officials have secured capacity for 28,000 people in hotels and inns. But less than 1,100 evacuees have chosen to move to such facilities as of Monday. Around 16,700 remain in emergency shelters.

Wajima City Mayor Sakaguchi Shigeru on Monday visited a local emergency shelter and urged evacuees to move to secondary shelters outside the city.

Sakaguchi says evacuees with medical conditions in particular should go, noting that they can't get proper attention from the city's overloaded hospital staff.

Some evacuees elect to leave

Ogi Yukio, 57, has been in a Suzu City shelter since New Year's Day, but now has decided to leave the area. He says he can't return to his home and has no proper place to sleep, leaving him no choice but to flee.

On Monday, a group of about 30 people, including Ogi, went to Kanazawa City.

Kurumada Yoneo, 85, lived in a rural area of Wajima City that was isolated by the quake. On January 12, he was evacuated by a Self-Defense Forces helicopter and transported to a Japanese-style inn in Kaga City with about 80 other residents from the same community.

Kurumada says he's relieved, but also sad because he doesn't know when he'll be able to return home. He says it could be six months, one year, two years or maybe never.

Those who choose to stay

Wajima City resident Aketa Motofumi, 73, has been living in an emergency shelter since the earthquake destroyed his house. But so far he's refusing to move to a secondary shelter because he feels he can't abandon his job and leave the work to others.

Hata Yukihiro, 48, who also lives in Wajima, looks after his mother. He says she's not fit to travel long distances, so he'd like to avoid relocating if possible.

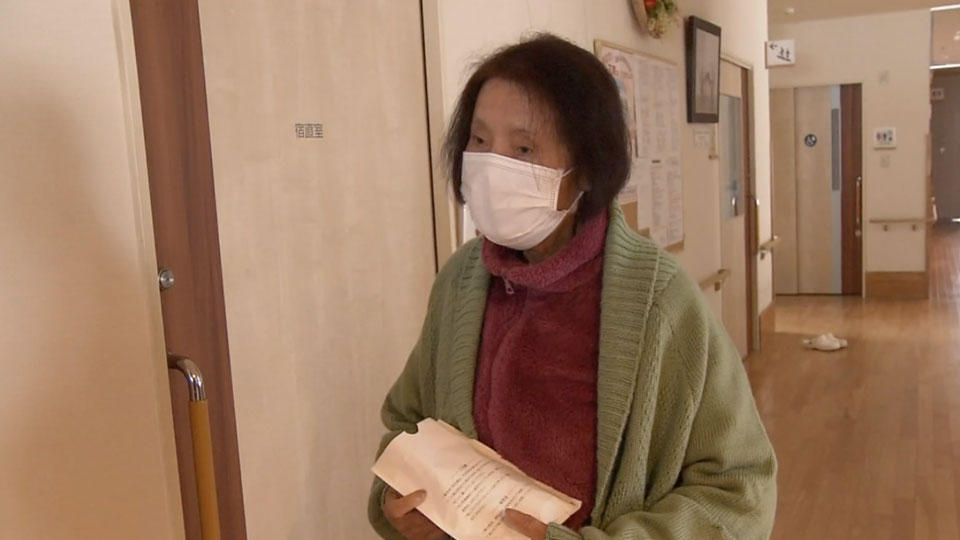

Suzu City resident Sakai Eiko, 80, says tsunami waves took her house, her car and everything else she owned. She's now staying in a facility for the elderly that's serving as an emergency shelter.

She says she has decided to stay for now because she needs to make regular hospital visits and wants to be seen by a doctor she knows. She adds that all her friends and acquaintances are in Suzu as well.

Sugano Taku is an associate professor at Osaka Metropolitan University.

He says conditions in disaster-hit communities' emergency shelters are poor, making the possibility of more disaster-related deaths a real concern. Evacuees should move to protect their lives, he adds.

Sugano says it's extremely important for the central, prefectural and municipal governments to provide evacuees with the information needed to make an informed decision about moving to a secondary shelter, including how they can live and what kind of support they can get.