Japan's "bubble economy" of the 1980s began to attract huge numbers of Philippine women seeking work. Their number peaked at 80,000 in 2004.

Many came to Japan on "entertainer" visas, a residency status granted to dancers and singers. But some did other work instead, and had relationships with Japanese customers. When they became pregnant, they returned to the Philippines to give birth, and then often lost touch with their children's fathers.

NHK spoke with two young JFC to hear about their quest for recognition and family connections.

Kigo's story

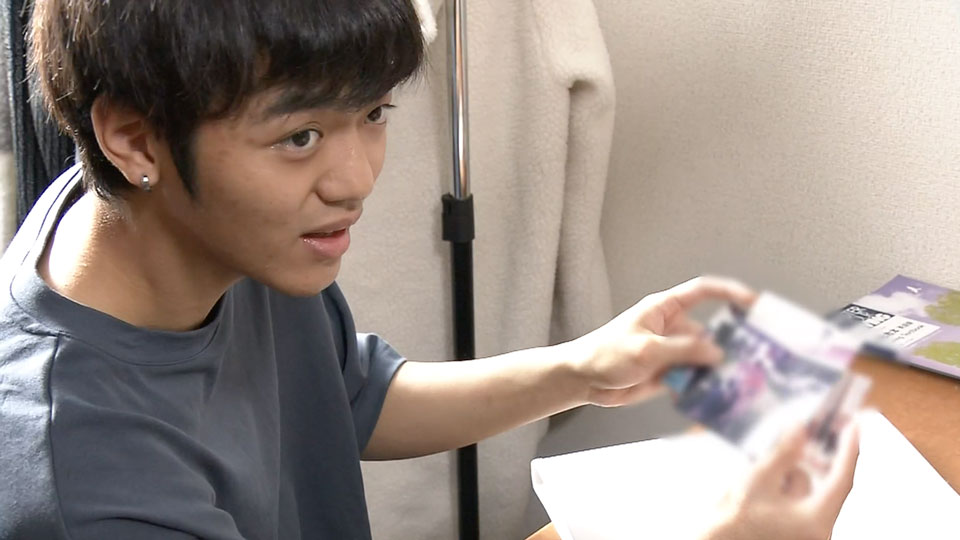

Kigo came to Japan in April and works at a factory in Yamagata Prefecture. He uses his father's Japanese surname, which is not included here to protect his family's privacy.

Kigo has never met his father but he has a photo of his parents.

"I feel like there's something missing about me," he said. "There's always a piece, a missing piece. There's so many questions I want to ask him."

To learn more about Kigo's story, NHK visited his mother Maria Juvie Villamor in the Philippines.

Villamor said Kigo's father was managing a Filipino pub in Japan when they met.

She had to return to the Philippines because her visa was going to expire, and she discovered she was pregnant. Kigo's father sent her money for about a year, but then abruptly stopped contacting her.

Kigo's mother said her son has continuously wished to meet his father, and he feels a strong connection to Japan.

"It's in his blood, because he's the son of his father. That's why he wanted to go to Japan before he turned 20," said Villamor.

Japanese citizenship eligibility

Kigo needed to complete his Japanese citizenship application by his 20th birthday.

Children of Japanese fathers can apply for citizenship before they reach legal adulthood at 20 if their parents were married at the time of their birth, or if they can prove their parent-child relationship some other way.

One day, members of a JFC support group visited Kigo with some life-changing information.

His parents were found to have been married at the time of his birth, according to his father's Japanese family register. This meant Kigo was eligible to apply for citizenship.

The support group decided to inform his father of the news. A group member called him and said, "We are now in the process of obtaining Japanese citizenship for Kigo and we think he'll be able to get it soon."

After a long silence, the support group member continued, "Kigo says he would like to meet you someday."

His father finally spoke.

"I work during the day..." he said. He did not agree to a meeting.

Kigo's face showed his disappointment. "I just want to see him. I don't want any financial support. Just his presence."

When NHK asked him what he would say to his father if they could meet, he responded, "I'll say, 'It's been a long time. And I finally see you.' And yeah, 'I forgive you for all what you did.'"

Aiko's story

Aiko, also identified only by her first name, now works in an auto parts factory in Gunma Prefecture. She will turn 20 soon. She hopes to acquire Japanese citizenship and live with her father in Japan.

Her father also had a Japanese wife and child, but he made an effort to keep in touch with Aiko's mother even after she returned to the Philippines to give birth. Aiko said he often visited them, but he lost contact when she was 10 years old.

"When I was a kid, I always called my dad, but my dad..." Her voice trailed off, and she crossed her arms in front of her to signal an end. "I'm sad, very sad," Aiko said.

Reunion after 10 years

One day, Aiko's father's whereabouts were discovered. He accepted a meeting with her, after a decade apart.

"Papa, I wanted to see you!" Aiko said to him in Japanese when they met, after she had spoken mostly in English with NHK.

Her father, now in his 80s, said he tried to bring Aiko to Japan after his relationship with her mother failed, but he said he was unable to do so due to various circumstances.

Aiko told NHK that while she has no money to give to her father, she will give him her care and love — even though he abandoned her for a long time.

"It's okay. I love my dad so much, and life's too short," she said.

Her father said he would try to help Aiko obtain Japanese citizenship. Preparations are ongoing, but it is not yet known whether her application will be accepted before her 20th birthday at the end of this month.

Foreign workers not seen as equal

Professor Ogaya Chiho of Ferris University in Yokohama specializes in multicultural information and assistance. She said the issues faced by JFC are regarded as personal problems, so public support for them is meager.

Ogaya said the lack of support is rooted in the fact that Japan does not see foreign workers as equal members of society, which she believes needs to change.

"It is necessary to see them as more than just a labor force," she said. "Japan should be thinking about how to accept and support them in other aspects of their lives, including childbirth and child rearing."