Sri Lanka's abandoned construction sites

Rusted steel building materials lie on the ground at the international airport near Sri Lanka's largest city, Colombo. A major Japanese construction firm was leading a project to expand its building. The work was being funded by more than $500 million in official Japanese aid.

According to the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), the Sri Lankan government, which has defaulted on its foreign debt, will not repay the loan.

Yamada Tetsuya, Chief Representative of JICA's Sri Lanka Office, said, "the impact has been enormous", with the Japanese construction firm withdrawing from the project.

Defaulting on over $36 billion in debt

Sri Lanka, grappling with a longstanding deficit, and typically reliant on imports, has tipped into crisis. Plunging tourism income due to global events like COVID and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, along with escalating food and energy prices, led to rampant inflation and currency devaluation. Unable to meet its foreign debt obligations, Sri Lanka officially defaulted in April last year.

Three months later, the economic turmoil escalated as angry citizens occupied the president's official residence. The president fled the country, leaving behind a staggering national debt of $36 billion.

More debt, more defaults

According to the World Bank, the combined debt of the world's developing countries has grown 1.5-fold over the past decade to about $9 trillion. Three nations announced that they have defaulted since the pandemic: Ghana, Zambia and Sri Lanka. The World Bank says nine of the world's 75 low-income countries are "heavily indebted" ― defined as unable to pay off what they owe. Another 28 are at high risk of falling into the same trap.

Inflation and rising interest rates

Why are developing countries running up debt and teetering on the edge of default? While multiple factors are involved, rising inflation in developed countries and the rapid interest rate hikes these countries use to tamp down demand are major factors.

In the United States, the Federal Reserve has raised interest rates 11 times since March 2022. The hikes have been paused for now, but they remain at their highest level in 22 years. The European Central Bank has waged a similar war on inflation.

This tightening of monetary policy in the developed world has led to a reduction in investment and the withdrawal of funds from many emerging and developing countries.

It gets worse. Debt already accumulated by poor nations, usually denominated in US currency or euros, is ballooning thanks to the higher rates. Governments and central banks in developing countries sold off dollars in a desperate bid to shore up their currencies, but without sucess. Foreign exchange reserves have fallen sharply, creating a vicious cycle that has made it even more difficult to repay foreign debt.

The wave of defaults arrives in Africa

A similar story of economic destruction is playing out in Ghana. The West African country announced in December 2022 that it would halt payments on its external debt.

The cash-strapped government has been forced to slash spending, impacting essential sectors of the economy. Funding has dried up for cacao farmers — Ghana is a major producer of the raw material for chocolate — resulting in pest-damgaged fruit rotting on the ground. The public health sector does not have the funds to hire nurses, leaving many new graduates unemployed.

Comfort Dadzie, 34, is raising a nine-year-old son. She borrowed money from a friend so she could finish nursing school. Nearly a year later, she has not been able to find work. She recently took up occasional housecleaning to makes ends meet.

"I have a child to take care of. I'm not working. I'm sitting in the house with older relatives. We're all very frustrated."

Easy money policy sparked the crisis

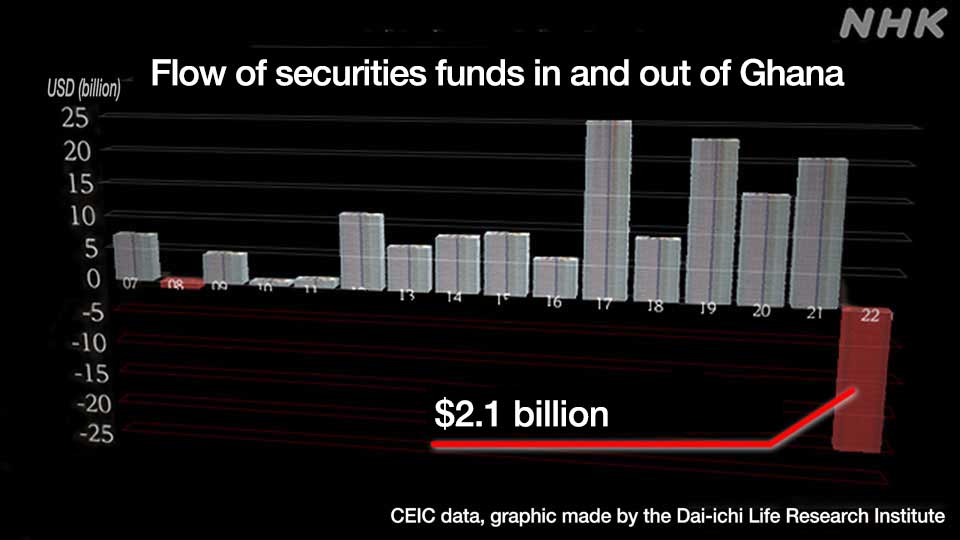

Not so long ago, Ghana's future seemed much brighter. Investments flowed into the country after the US and Europe embraced expansive monetary policy in 2012. High-yield Ghanaian government-issued bonds raised over $2 billion – sold on the promise of a stable political system and an abundance of mineral resources.

Fast forward a decade, however, and the negative aspects of easy money policy have led to a rude awakening.

Interest rate hikes from 2022 onward caused a sudden reversal in the flow of global funds. Currencies collapsed, interest payments on debt ballooned. By the end of the year, as much as $2.1 billion had left Ghana, leaving the country unable to repay its debt. A senior finance ministry official says investments have dried up, and the situation is helpless.

"Our debut on the Eurobond market was historic," says Alhassan Iddrisu of the Ghanaian Ministry of Finance. Looking back on what went wrong, he says "We were on time, we paid our debts, until unfortunately, we were hit by those external shocks."

Easy money hangover

Some experts say the world should have been wary of the pitfalls of easy investment money. Professor Raghuram Rajan of the University of Chicago and former Governor of the Reserve Bank of India, was one of those who tried to raise the alarm.

"What you see is an easy period before. That's when people think, 'Oh, things are getting better. Let's borrow.' That's when you need maximum restraint. You want to be very careful then, look at what your capacity is for borrowing, for repayment, and tailor your coat to fit the cloth that you have," he explains.

He says many countries that overindulged in easy money are now suffering a hangover.

Effects on ordinary people

A year and a half after the default in Sri Lanka, the economic crisis continues. The World Bank estimates that the national poverty rate stands at almost 30 percent. That's more than double the figure in 2021.

For Colombo residents like the Ranatunga family, straitened circumstances mean eating in the dark. They say they hardly use electricity anymore because their power bill has gone up significantly over the past year. They can only afford to make the thinnest curries, with the only bulk coming from seasonal vegetables such as pumpkin ー when they can afford it.

The 90-year-old family matriarch used to receive free treatment for an injured leg at a public hospital. But the increased cost of medicines means the hospital has nothing left to give her, nor many others.

IMF offers advice

Peter Breuer, International Monetary Fund Senior Mission Chief for Sri Lanka, says austerity is the only path forward. "Tax revenue needs to be raised in order to narrow the gap between expenditures on the one hand and how much the government takes in on the other hand. We realize that is painful domestically, [but] it is one part of the adjustment that needs to take place in Sri Lanka."

The Sri Lankan government is attempting to respond to these calls. The country's value-added tax has been raised to 15 percent, up from 8 percent. The country has also more than doubled electricity prices, but it still has a long way to go to win back the trust of international investors.

Sri Lanka's President Ranil Wickremesinghe tells NHK, "I think there have been no finance studies on the financial viability. The issue is that for a given period, we have taken actually too many loans whether we are taking it from China, other countries, or from the bonds that have been issued, and this has weighed heavily on the economy."

The country's leaders face a difficult challenge, however, as they seek to satisfy creditors and other outside parties, while inflicting the minimum pain on citizens who are already feeling the pinch.

A crisis looking for a solution

The crises in Sri Lanka and Ghana lay bare how poorer nations are left to bear the brunt of the consequences from monetary policies of richer nations.

Professor Rajan says the solution is to rein in central banks. In a March 2023 article published by the IMF, he explains that central banks have taken on too much. He wants them to narrow the focus of their policies so as to reduce the effects of their decisions on other countries. "When it comes to economic policy, this mentality of 'less is more' benefits all parties involved," he writes.

Some economists will disagree on policies and mechanisms. Still, it has become clear that the world needs to focus on growth for all nations, with a new strategy that minimizes disparity and division.