A hardscrabble life

The photo was among a set of pictures of people detained by the US military as prisoners of war, demonstrating that Peragia Diamona, whose Japanese name is Hoshiko Haruko, is the offspring of a Japanese national.

Haruko lives in a shack made of woven bamboo two hours by car from Davao, the main city on the southern Philippine island of Mindanao. The shelter lacks running water and is a testament to the hardscrabble conditions in which she has spent much of her life.

A prosperous immigrant community on Mindanao

Japanese immigrants began arriving on Mindanao in 1903. Many turned what had been jungle around Davao into fields for growing hemp, important because it was used to make ropes for ships, including naval vessels. Before World War Two, as many as 20,000 Japanese lived in the area, making it the largest immigrant community in Southeast Asia.

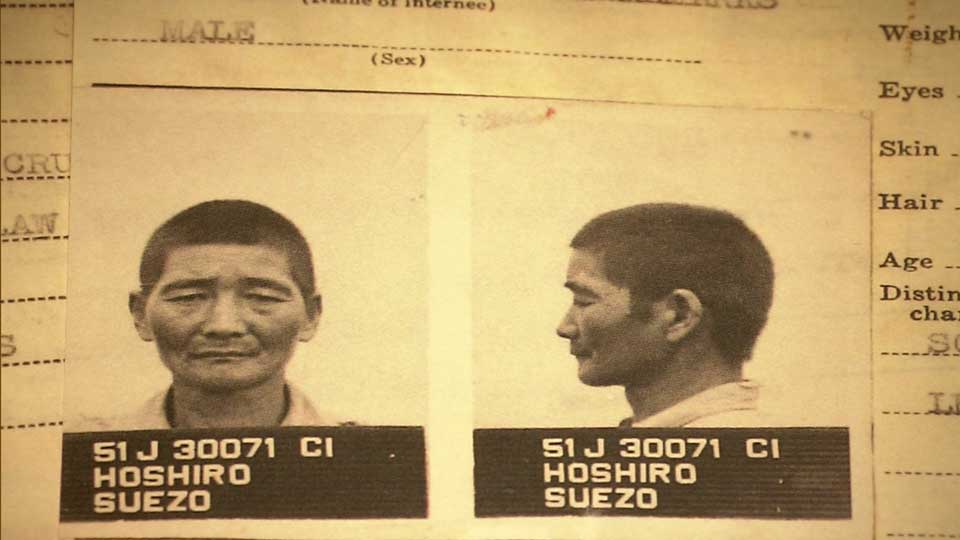

Most Japanese immigrants were men who started families with local women. Haruko's father, Hoshiko Suezo from Kumamoto Prefecture, was one of them.

Suezo and Marcelina had nine children, of which Haruko was the seventh. Having arrived before the war began, he had made a success of himself in hemp cultivation and fishing. The family was well off and spoke Japanese.

Goodbye to all that

But World War Two swept all that away. On Mindanao, Japanese forces engaged in fierce fighting with US troops and local guerrillas. Haruko's family was caught up in the war, and Suezo was forced to act as an interpreter for the Japanese army.

"A Japanese military post was being built on the beach near our house," says Haruko. "Japanese soldiers would bring residents suspected of being Filipino guerrillas to my father. And my father, who could speak the local language, would translate for them and investigate them to see if they were hostile."

It was not unusual for someone to be executed simply on suspicion of being a guerrilla, which contributed to growing hatred between Japanese immigrants and locals.

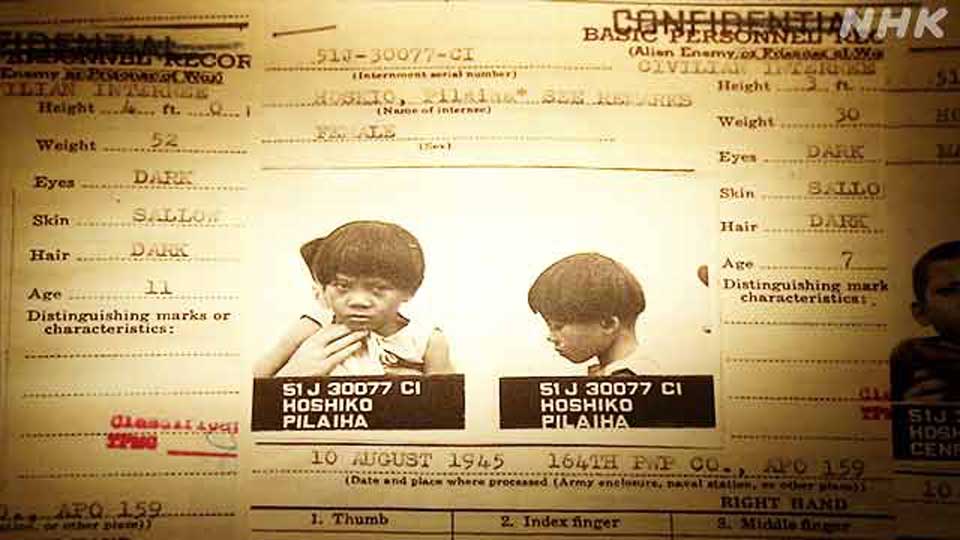

The family eventually took refuge deep in the mountains, where they were sheltered by indigenous people. As the war was coming to an end, Suezo decided to surrender to the US military to save the lives of his family. That was when they became POWs and were sent to a camp for Japanese nationals.

"We were not allowed to take a step outside the wire fencing that surrounded the camp," says Haruko. "For six months, we lived like cattle in a building that provided little shelter from the wind and rain."

"My father wanted to take all of us children to Japan. But he could not get permission to take everyone. The US soldiers told him that young children were not allowed," she says. "When we said goodbye, my father was crying and left without looking back at us."

Only her father and her three older brother and sister, aged 15 and above at the time, were allowed to make their way to Japan. Haruko's mother and six younger children were left behind.

Facing discrimination

A survey that has been carried out by Japan's foreign ministry since 1995 indicated that at least 3,800 children of Japanese descent had been left behind in the Philippines after the war.

The children faced discrimination as offspring of an enemy nation that had inflicted many casualties on the Philippines. Haruko's family home was burnt down and their possessions confiscated in the aftermath of the war.

They destroyed everything that showed any connection to Japan or to Suezo, and spent their days hiding in the mountains. She recalls that she was unable to go to school and says the family subsisted on meager rations.

Haruko's mother suffered from a heart ailment and died at the age of 50 some ten years after the war. Haruko and her siblings managed to feed themselves with farming.

When she was 27, Haruko married a local, and they raised six children while cultivating a small farm. They remained poor, however, and Haruko says she and all the siblings who stayed behind regretted not being able to go to Japan.

'I am Japanese'

Anti-Japanese sentiment in the Philippines began to wane in the 1980s, when Japan began providing economic assistance to the country. People of Japanese descent who had remained behind, hiding their heritage, finally began to speak out. They formed Japanese associations throughout the Philippines and began searching for their fathers.

A turning point came in 1995, when Japan's foreign ministry conducted the first survey on people of Japanese descent left behind in the Philippines. Haruko and her siblings participated, and were recorded as being of Japanese descent.

Haruko expected to be recognized as a Japanese citizen and to meet her father. But the survey was conducted only to determine the number of people who remained in the Philippines, and no effort was made to grant them official recognition.

"My father was Japanese, so I am Japanese too, right? It's obvious," says Haruko. I had been praying to see my father and my brother and sister."

In the name of the father

In the past, both Japan and the Philippines assigned nationality based on the citizenship of a child's father. If a father was Japanese, the child automatically became a Japanese citizen. Most of those left behind were unable to prove that their fathers had been Japanese because they had destroyed documents and photographs that would have provided evidence. This left many of the remaining people of Japanese descent stateless.

The Philippine Nikkei-jin Legal Support Center, a non-profit organization based in Tokyo, has been helping such people in their effort to gain recognition for the past 20 years.

The NPO tries to locate and interview people of Japanese descent who remained in the Philippines. The organization also searches for documents and other materials proving a connection with a Japanese father.

The evidence is then submitted to a family court in Japan as part of a bid to get permission for a new family register ― an essential part of the process for gaining citizenship.

Over the past 20 years, more than 300 people have been granted Japanese citizenship. Another 1,780 had passed away by the end of March of 2023 without being recognized as Japanese. According to Japan's foreign ministry, at least 151 of the remaining people of Japanese descent alive today are stateless.

NPO representative Inomata Norihiro says the group has called on the Japanese government to recognize the nationality of all those with a plausible connection to Japan, without putting them through the time-consuming court procedure.

New evidence

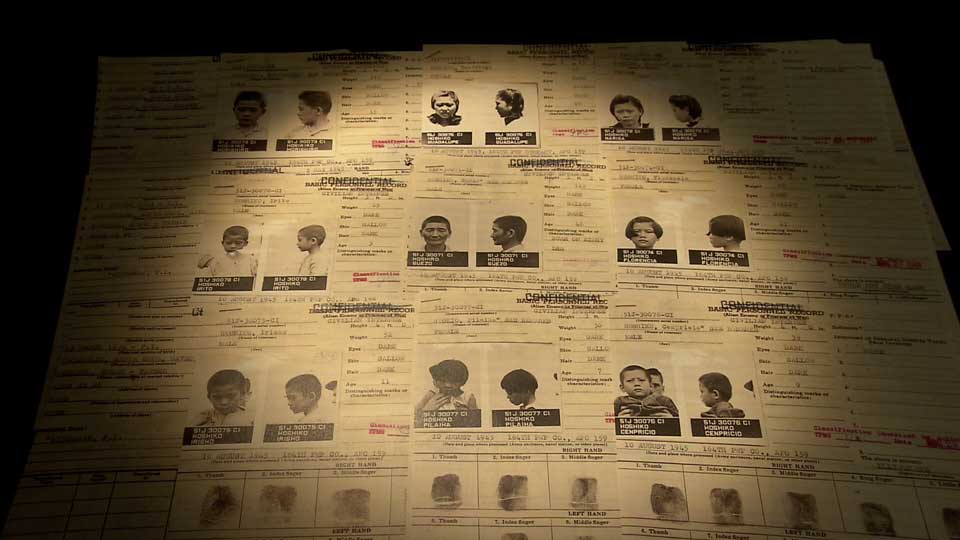

The NPO then discovered a list of Japanese prisoners of war in the Philippines compiled by the US military.

Haruko and her family members are recorded in the list, which runs to 18,000 people, held by the US National Archives and Records Administration.

"There is no way the family could have gained access to this evidence on their own," says Inomata. "It brought home to me once again that these stateless people need our help."

Wishes fulfilled and not fulfilled

In June of 2023, the NPO filed an application with the family court in Kumamoto Prefecture, her father's place of origin, on Haruko's behalf. Permission to create a new family register, and with it Japanese citizenship, was granted just over a month later.

"I have good news for you today. You have been officially recognized as a Japanese national," Inomata was happy to report. Haruko smiled but did not seem to quite take in the full meaning of what she was being told.

With the report, Inomata handed Haruko a picture. "This is Miyoko, your sister. She passed away in 2009," said Inomata. The picture shows Miyoko, who went to Japan with her father after the war, in her later years. Miyoko's family wanted Haruko to have it so that she could at least lay eyes on her sister, even if a meeting was now impossible.

Haruko gazed at the photo as tears welled in her eyes. "I am happy to be recognized as a Japanese. But I am sad and lonely. I am so old now, and I was never reunited with my father and sister," she says.

Time is running out

With an average age of over 83, time is running out for people of Japanese descent who wish to be recognized. There are few cases such as Haruko's, in which substantive evidence is found to back up a claim to citizenship. Statelessness, discrimination and the pain of separation have haunted Haruko for most of her life. For her and others like her, it can only be hoped that recognition comes before it's too late.