In September 2022, a Hong Kong court sentenced five young people to 19 months in prison for publishing a series of picture books. In one, a pack of wolves attempt to enforce new rules upon a village of sheep.

The works were described as "seditious."

The ruling said any children who saw the book would identify the Chinese government as the wolves, adding that they would then develop a hatred for central authorities after being led to believe that leaders in Beijing would come to destroy their happy lives in Hong Kong.

Authorities define "sedition" as the intent to incite hatred, contempt or dissatisfaction with the Chinese or Hong Kong governments. It is stipulated as a punishable act under the Crimes Ordinance, which had not been used since a series of riots in 1967, when Hong Kong was under British rule.

These days, the maximum penalty for first offenders is a fine of HK$5,000 (about US$640) and two years' imprisonment.

The picture books are now extremely scarce in Hong Kong.

In March this year, a 38-year-old male was arrested for obtaining multiple copies from the United Kingdom. He was later charged with importing seditious publications — the first case of its kind since Beijing imposed the national security law on Hong Kong in 2020.

This month, he was sentenced to four months in jail after pleading guilty.

The judge criticized the defendant for importing publications that indoctrinate children with hatred, contempt and disaffection towards central authorities. He also said the defendant's act might encourage others living overseas to continue publishing seditious publications.

Earlier this year, a 23-year-old woman was arrested in Hong Kong after returning from Japan, where she had been studying. She was accused of inciting secession by posting comments online in favor of Hong Kong's independence. She was later charged with carrying out seditious acts.

Protesters worried about past actions

Other young people are growing increasingly fearful — especially those who took part in widespread pro-democracy protests that erupted in 2019 after the government proposed a bill to extradite criminal suspects to mainland China.

The protesters included Yeung (pseudonym), who served 21 months in jail for rioting.

Since being released, she has deleted all her photos and comments from social media. She fears her past actions could be punished in the near future.

Hong Kong's government urges people to disclose anything they deem a threat to national security. As of May, a dedicated contact point has received more than 500,000 reports.

"Sedition is extremely wide-ranging," says Yeung. "The scariest part is that even if I don't mean it, someone else might think I do. And I could go to prison again."

Yeung is now extremely careful about what she says in public, and she no longer keeps in touch with friends who harbor different political views.

Authorities have arrested more than 10,000 people for participating in the protests and other anti-government activities since 2019. About 4,000 were students at the time.

The South China Morning Post, a local English-language newspaper, says there could be as many as 6,000 waiting to learn their fate.

Many have been granted bail, but that's done nothing to ease their worries. One lawyer says the fear of a sudden visit from the police is taking a heavy toll on their mental health.

"People go to work and return home," says Yeung. "Things seem to be normal, but they have no hope. Right now, I have no plans for the future."

Candles strike a nerve with authorities

Debby Chan is a former district council member from Hong Kong's pro-democracy camp who took part in a massive anti-government protest in 2019. Four years on, the 33-year-old says life has only grown more precarious.

"The problem is, the line that should not be crossed is unclear. We've been doing the same thing year after year, so why has it become a problem now?"

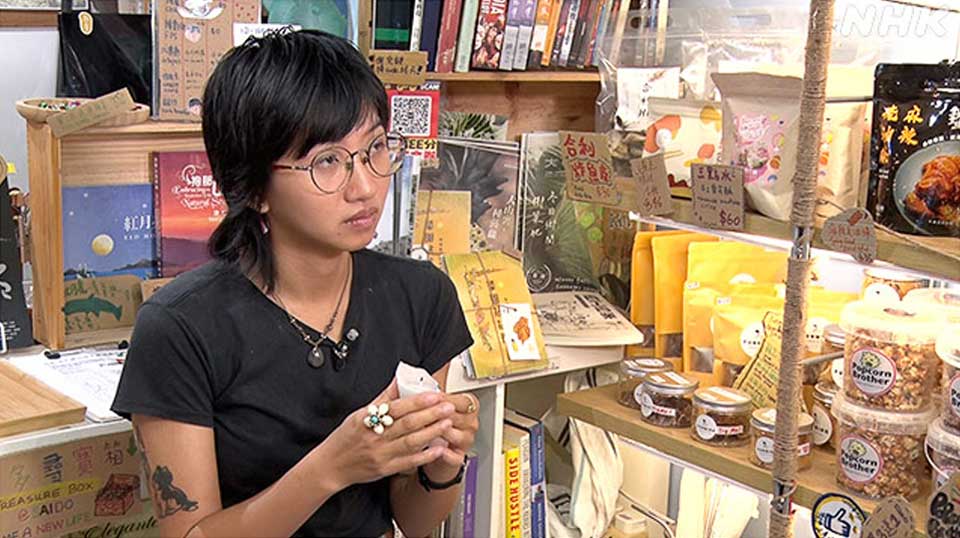

These days, Chan owns a small shop selling beer, sweets and other goods made in Hong Kong.

But in May, she found herself under police surveillance for handing out candles, which had been used every June 4 to commemorate the 1989 Tiananmen Square incident.

Rallies in Hong Kong to remember the victims drew 180,000 people at their peak. And the candles came to symbolize freedom of expression.

But after almost 30 years, those gatherings are no longer allowed.

On June 4 this year, the police were out in force, patrolling the main area where people used to rally.

NHK saw one woman, who was holding a bouquet of flowers, being taken away. More than 20 others suffered the same fate, and one person was arrested on suspicion of obstructing official duties.

The next day, the police showed up at Chan's shop. They took issue with a picture of a candle hung outside. They said it had the "intent to incite," and promptly took it down.

"Aren't we allowed to display candles in Hong Kong? I don't understand," says Chan. "This is clearly police pressure. They are trying to scare people, and make us self-censor."