Yamada Yuji is the vice-president of Mie University's International Ninja Research Center.

Q: Can you tell us what ninjas were really like?

Yamada Yuji: I know many people have this image of ninjas in all-black costumes using a range of wild weapons or performing acrobatic moves while fighting, but that rarely happened. And their iconic weapon, the shuriken, or throwing star, was actually used by samurai — not ninjas. There's no credible record to show that ninjas used such a weapon.

Nor was there ever an all-black uniform. Ninjas routinely changed their appearances to blend in with crowds. So they might dress up as travelers or monks, for example, to avoid detection. An illustration in a 17th-century manuscript shows ninjas who look just like samurai.

They're also known for infiltrating buildings, but their most important skill was infiltrating people's hearts. They were brilliant at getting people to reveal things they wouldn't normally tell anyone else.

The contemporary stereotype of the ninja that we see in movies and books today originated in kabuki theater in the early 1700s and evolved through popular culture.

Ninja tradition dates back to the 1330s. During the Warring States Period [1467-1590], ninjas did sneak into castles, and sometimes set them on fire. But once peace was established in the 17th century, ninjas lived in castle towns and helped to maintain public order. They were mainly employed by feudal lords to spy on regional rivals or to guard castles.

But their most important mission during these times, I would say, was always the same: To gather information and bring it safely back to their masters. I don't think they fought as much as we imagine. In fact, they tried to avoid fighting whenever possible.

Q: What are some other misconceptions about ninjas?

Yamada: The image of the ninja has changed with the times. It's really interesting. For example, there's no public record of female ninjas, but now we have this idea that they went on missions with their male counterparts, right? The idea of the female ninja is actually a relatively new one. It only emerged after World War Two.

In fact, the term "ninja" didn't take root until the 1950s either. Previously there were other names for them, such as "shinobi."

Q: So where do all these misperceptions come from?

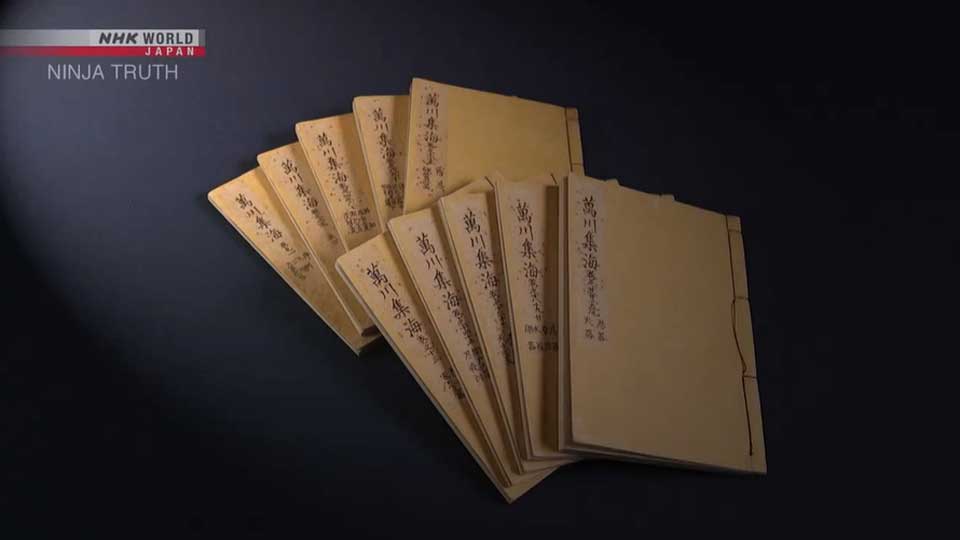

Yamada: Ninja arts were mostly passed down in secret from master to student, so there aren't many public records. There were probably several reasons for this, but the most obvious is that they didn't want other people to steal their secrets. Also, they simply weren't able to write them down. It would've been hard for them to explain the ninja arts on paper. That's why the manuscripts we have now usually only have bullet points and no other detail. The lack of detail is what fuels our imagination. Because we don't know for certain what the ninja arts involved, storytellers have used their imagination to fill in the gaps, transforming ninjutsu into something very exciting.

Kawakami Jinichi is known as "the last ninja." The 74-year-old has been studying the ninja arts for most of his life. He started his training at the age of 6, without even knowing the true purpose. When he was 18, Kawakami received ninja manuscripts that had been passed down over generations.

Q: What do you regard as the true ninja arts?

Kawakami Jinichi: In my understanding, ninjutsu is a set of skills for survival. It's always been based on the latest technology of the time. If we think about it in contemporary terms, it can include the latest knowledge in medicine, pharmacology, biology, meteorology, and psychology, and so on.

I feel as if people nowadays only understand a part of what ninjas are. They think of them as being spies or superhuman beings. They focus more on the fighting aspect, which I think is a bit of a shame. I wouldn't say that perception is completely wrong, but that's not the whole picture. It's just a small part of it.

Of course, the manuscripts I've reviewed do include descriptions of fighting or military techniques. But I don't think they're so useful or relevant for us today. They're quite dated.

Q: Is there anything we can learn from ninjas today?

Kawakami: Absolutely. We could definitely benefit from the ninja mindset. During the Edo era, which was a largely peaceful time without battles, ninjas started prioritizing the mind over the body.

Through decades of training, they learned to be patient, to stay calm whatever happened, and to avoid fighting…that was the core of ninjutsu, as far as I understand it. Be patient — that means you don't create enemies. Instead, you build relationships with people. Good communication skills were indispensable for this. This is what being a ninja was and is all about.

Knowing your limitations is another thing. You have to acknowledge what your limits are to complete a mission. Basically, again, ninjutsu is about staying alive and being in harmony with nature.