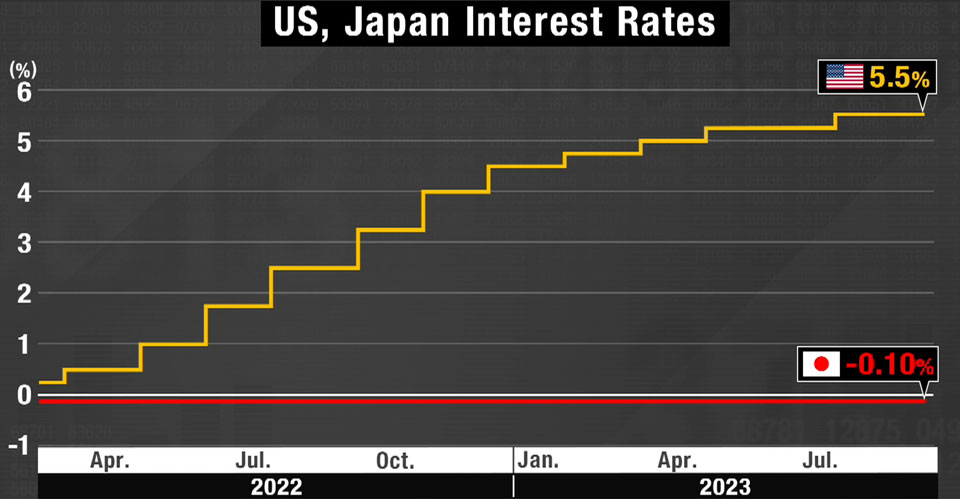

Japan's central bank has kept the overnight rate around zero for more than a decade. In the United States, the Fed has been taking a markedly different approach, steadily raising rates since early last year in a bid to rein in inflation. The rate now ranges between 5.25 percent and 5.5 percent.

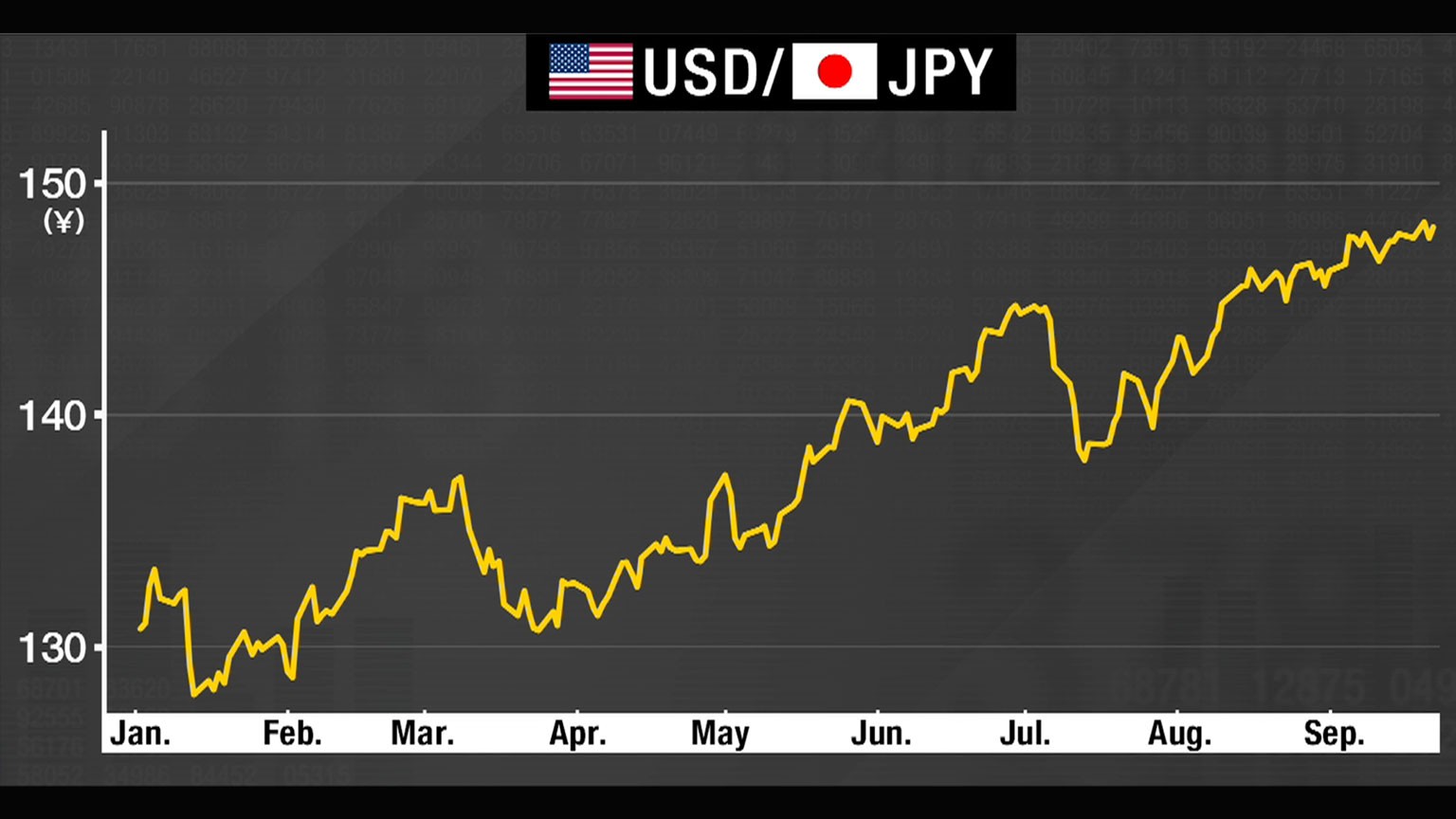

Investors are taking advantage of this yawning disparity, selling yen for dollars to claw in higher interest, and weakening the Japanese currency in the process.

After the Fed's most recent meeting, last week, policymakers sent a clear signal that more hikes are on the horizon. The timing of the BOJ announcement, which followed just two days later, entrenched the perception among currency traders that the difference in policies ― hawkish in the US and dovish in Japan ― will persist for the foreseeable future.

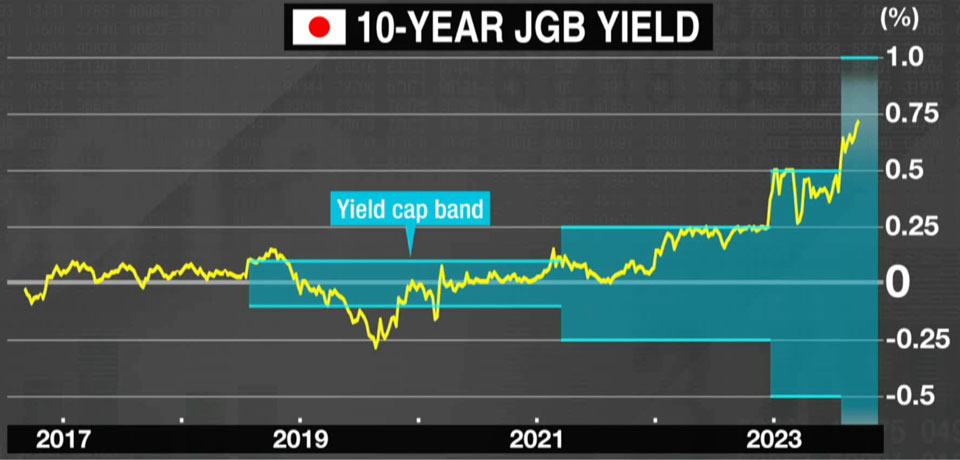

The BOJ decision means it will keep its short-term benchmark interest rate in negative territory, and continue buying assets at a level to keep long-term rates at "around zero percent." It will also maintain its yield curve control program, which limits returns on 10-year government bonds to a tight band ranging from around minus half a percentage point to plus half a percentage point, with a hard cap at 1 percent.

Comments by the BOJ Governor Ueda Kazuo in the lead-up to the meeting had spurred speculation that a policy shift might be on the way.

But Ueda took a different tone at the post-meeting news conference. "It's not yet possible to foresee the sustainable and stable achievement of 2 percent inflation," he said. "That's why we need to continue with our monetary easing."

The BOJ chief noted that "uncertainty over economic activity and prices is extremely high. It's impossible to decide when to revise the policy and what specific measures to take."

The central bank's resolute commitment to its massive easing program comes in the face of stubbornly high consumer prices. Data show's Japan's core inflation hit 3.1 percent in August, making it the 17th straight month that it has exceeded the 2 percent target.

Economists say the continuing price pressure is largely due to high import prices, which are a result of the weakness in the yen. They say if the BOJ raises rates, thereby reducing the gap between Japan and the US, it could boost the value of the yen and ease inflation.

But they add this scenario is precisely what concerns the policymakers at the BOJ, who believe weak consumption could cause inflation to drop too far, too fast, dragging Japan back into the deflationary mire that bogged the economy for decades after the collapse of the bubble in the early 1990s.

The safest path, so the thinking goes at the central bank, is to keep things as they are.

Keio University Professor Shirai Sayuri, who served a 5-year term on the policy board at the BOJ, believes this mindset is fundamentally flawed. She says personal spending power alone will never be strong enough to drive inflation to 2 percent.

The past 20 years is evidence enough to back this up, she says. Consumer spending has remained persistently weak throughout the two-decade period, and as a result inflation has never come close to 2 percent. The situation won't change anytime soon either, as the population ages and more people live on pensions, while younger generations eke out a living on stagnating wages. If anything, she says, consumption will only get weaker.

The way Shirai sees it, there won't be any drastic changes from either the BOJ or the Fed in the near future. For struggling Japanese households that are increasingly cutting corners to get by, that will be a bitter pill to swallow.