Located in the traditionally Latino working-class neighborhood of the Mission District, just a few kilometers from some of San Francisco’s wealthiest tech companies, Arriba Juntos and the clients it serves may as well be from a different economic planet. Today, like on most days, the food was brought to the nonprofit by Copia, a tech company that specializes in stopping food from going to waste and onto the plates of those who need it. “Copia has been with us for a long time and they help us feed everybody,” says Gladys Garcia, program coordinator at Arriba Juntos.

Copia, based in San Francisco and operating in a handful of cities across the United States, is a technology platform that connects over 100 companies, which include hospitals, restaurants, and universities, with 150 nonprofits across the San Francisco Bay Area for same-day food donations. When a business has high-quality surplus food, they log into the Copia app, enter the type and amount of food they wish to donate, and the app matches the donation with a local nonprofit for same-day delivery. The nonprofit pays nothing, Copia collects from US$500 to US$2,000 per month from the business depending on how much it uses the service, and the business gets tax deductions from their donations as well as the good publicity. “Hunger is not a scarcity problem, it's a logistics problem. And it’s that very logistics problem that Copia has the technology to solve,” says Founder and CEO Komal Ahmad.

According to the Natural Resources Defense Council, 40% of America’s food goes to waste, an equivalent of 181kg per person. In California, one in 8 residents suffers from food insecurity, while in San Francisco -- where a household income of US$117,000 is considered low income -- that figure rises to one in 4. “This is the tech capital of the world. It’s very ironic that in Silicon Valley, one of the wealthiest places not just in our country but on the planet, one in 4 doesn’t know where his or her next meal is going to come from,” Ahmad adds.

In recent years, tech has responded to the call. Apeel Sciences, founded in 2012 with a grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, developed a second “peel” to extend the shelf life of certain fruits and vegetable. And just this year, San Francisco based business-to-business platform Full Harvest, which connects companies with farms to buy surplus and imperfect produce, raised US$8.5 million dollars to expand its operations. But solutions to the food waste problem aren’t just coming from the tech intelligentsia of California.

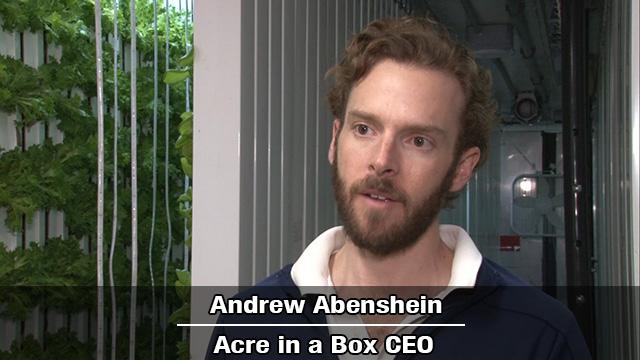

Three thousand kilometers away, in Houston, Texas, Acre in a Box, in conjunction with Boston-based Freight Farms, is reimagining old-fashioned farming to cut waste all together. The company, founded by Andrew Abenshein and Ana Buckman, grows 500 to 600 heads of lettuce per week on 2 customized shipping containers and delivers the produce within a 5 mile radius of downtown Houston to a customer base that includes restaurants and grocery stores. “From a food waste perspective, we are able to deliver exactly what the customer wants, so we never have anything that is being wasted. We can grow on demand. And with that and the distance that we’re in and our customer base, we only have to travel very short distances to make sure that it gets there,” says Abenshein.

The 40 foot shipping containers built by Freight Farms can grow an acre of produce each and contain a seedling area to plant and harvest, 4,500 growing sites throughout 256 crop columns, and are outfitted with an automation system, LED lights for artificial sunlight, and an irrigation system. In a nutshell, it’s a farm inside a container. “When you think of the produce that’s grown in California and driven all the way to Houston, you’re going to have some loss there,” Abenshein says. “With our produce, there’s no transportation and so it only stays in our car for 5 minutes, 10 minutes.”

Back in San Francisco, Copia, which recently agreed to expand its services with the NFL’s San Francisco 49ers and cover the restaurants in the team’s 68,500-capacity stadium, is aiming for more. “I want to solve hunger globally,” Ahmad says. “I want to be able to create technology that reduces food waste on a global scale. This is not just an American issue or a Japanese issue. It is a global issue and we know that we have the resources, the technology, and the will to solve it.”