"Diversushi"

For the vision-impaired, dining out is usually a hassle. They need to figure out where everything is, starting with the cutlery. Then they need to find the food on the plate, make bite-sized pieces, pick them up and maneuver the pieces into their mouths.

Narisawa Shunsuke, who lost his sight in his 20s, notes: "It's lonely when I can't enjoy food in the same way as the people I'm dining with." When friends ask him out for a meal, he often suggests a sushi restaurant, not necessarily for the taste, but because sushi is easy for him to eat due to the etiquette: by hand.

With that in mind, Narisawa and a friend, Ochiai Yoichi, are setting out to improve dining options for the blind. They have devised a new genre of food that's hassle-free for people who can't see, and also enjoyable for those who can.

They call it "diversushi," a mashup of diversity and sushi. The concept has three points: it can easily be picked up by hand, eaten in one bite and is appealing without relying on sight.

Even though it has "sushi" in its name, the cuisine goes well beyond seafood and rice. For example, ravioli diversushi comes with sliced baguette underneath that allows diners to pick it up.

A special dining event was held in Tokyo in July to introduce people to diversushi. Guests included people with and without sight. "The concept is a dining experience that a diverse group of people can enjoy in their own way. The imaginative menu is designed for not using cutlery, but your hands," Ochiai said in his welcome speech.

The meal started with single-bite foie gras on a wooden cube, served on a ribbed plate. Diners could touch the plate from any angle, find the wooden cube in the middle, then pick it up. The dish was designed to be accessible without sight. As an added bonus, the diners were able to avoid getting sticky fingers.

Experiential dining

Chef Murayama Taichi was in charge of the menu. "Diversushi isn't about simply making finger-food, or adjusting the dishes for those who can't see. It's about making the dining experience seamless for them, and allowing those with sight to share that," he explains.

For a meat dish, Murayama wrapped wagyu in a sheet of cedar. Diners could untie a string to access the tasty morsel without relying on sight in a process that also allowed them to feel the woody texture and enjoy its aroma.

Conversation during the evening was insightful about the many challenges for blind diners. One man noted he sometimes misses his dining partner's glass during a toast, and has even broken his own.

The way forward

Narisawa and Ochiai are planning more events, and they hope diversushi will spread as a concept. They say they look forward to seeing what chefs around the world can create with their own cuisines and cultures.

Soft food with "soulage"

Japan's aging population includes many people who suffer from dysphagia, or swallowing disorders. They often have no choice but to eat food that comes in the unappetizing form of a puree.

One chef has come up with a way to reintroduce fine dining to their lives with what he calls "soulage," which means "relieved" or "no longer worried" in French.

A feast that's easy to swallow

Kato Eiji, owner and chef of French restaurant "Maison Hanzoya" in Yokohama, has a full-course meal that can be enjoyed by people who find it hard to swallow. He uses different ways to soften food.

Kato's own experience when he was ill in hospital has informed his approach. He saw other patients being served unappealing pureed food.

"People with dysphagia usually only eat foods with similar textures. I wanted to find ways to change that, so that they can enjoy fish and meat that retain their unique textures," he says.

Kato has studied human digestion and enjoys experimenting with various foods.

A scientific approach

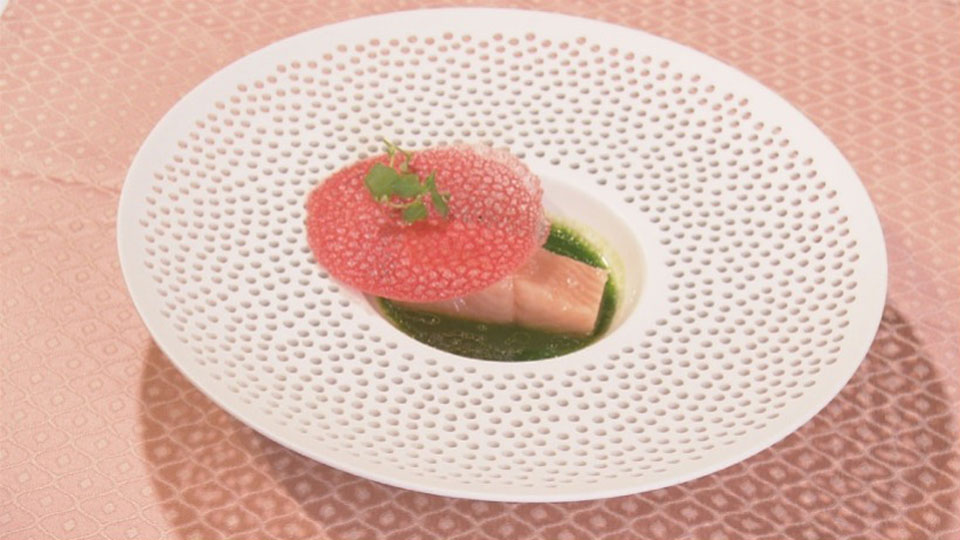

Kato has a method to simmer cherry salmon in oil at 40-48 degrees Celsius. He says this breaks down even the smallest fibers in the fish, noting that higher temperatures harden the fibers.

His cherry salmon dish melts in the mouth. It is served with pureed turnip leaves, thickened to help swallowing.

Kato explains: "When people eat, their airway reflectively closes, while the food pipe opens. This is how our bodies keep food from entering the lungs. The deterioration of this system leads to dysphagia. The airway closing and the food pipe opening don't happen as quickly, so foods and liquids hit the airway. That can lead to gagging, or in severe cases, food entering the lungs. But if food is enveloped in thick substances, it reaches the back of the throat slowly, giving the airway time to close."

Using ingredients with purpose

Kato likes to employ the properties of particular ingredients. For edamame soy bean custard, he uses only the yolk rather than the whole egg. That's because if the dish is made using the whole egg, each bite comes with juicy liquid seeping out ― a gagging risk. Kato's fix stops that from happening.

Sharing knowledge

Kato sometimes hosts tutorial sessions for other chefs. He even shares the recipe for his signature main dish, wagyu in red wine sauce.

The beef is marinated in red wine vinegar for two weeks. Kato says the enzymes help soften the meat. On the day it is to be eaten, the dish is cooked for four hours. "Meat tendons turn into gelatin when simmered for a long time. This makes it super-soft," he shares.

A chef who traveled from Osaka for Kato's tutelage notes, "I had this preconception that food for people with dysphagia had to be a smooth puree. But now I realize that texture and appearance can be maintained. What an incredible learning experience!"

Everyone at the table

Kato believes the best way to eat is with everyone at the table enjoying the same things. That's why he includes some of his easy-to-swallow recipes on his restaurant's regular menu: "My goal is for everyone, including people with swallowing disorders, to be able to enjoy the same dishes while dining together."