The work of an embalmer

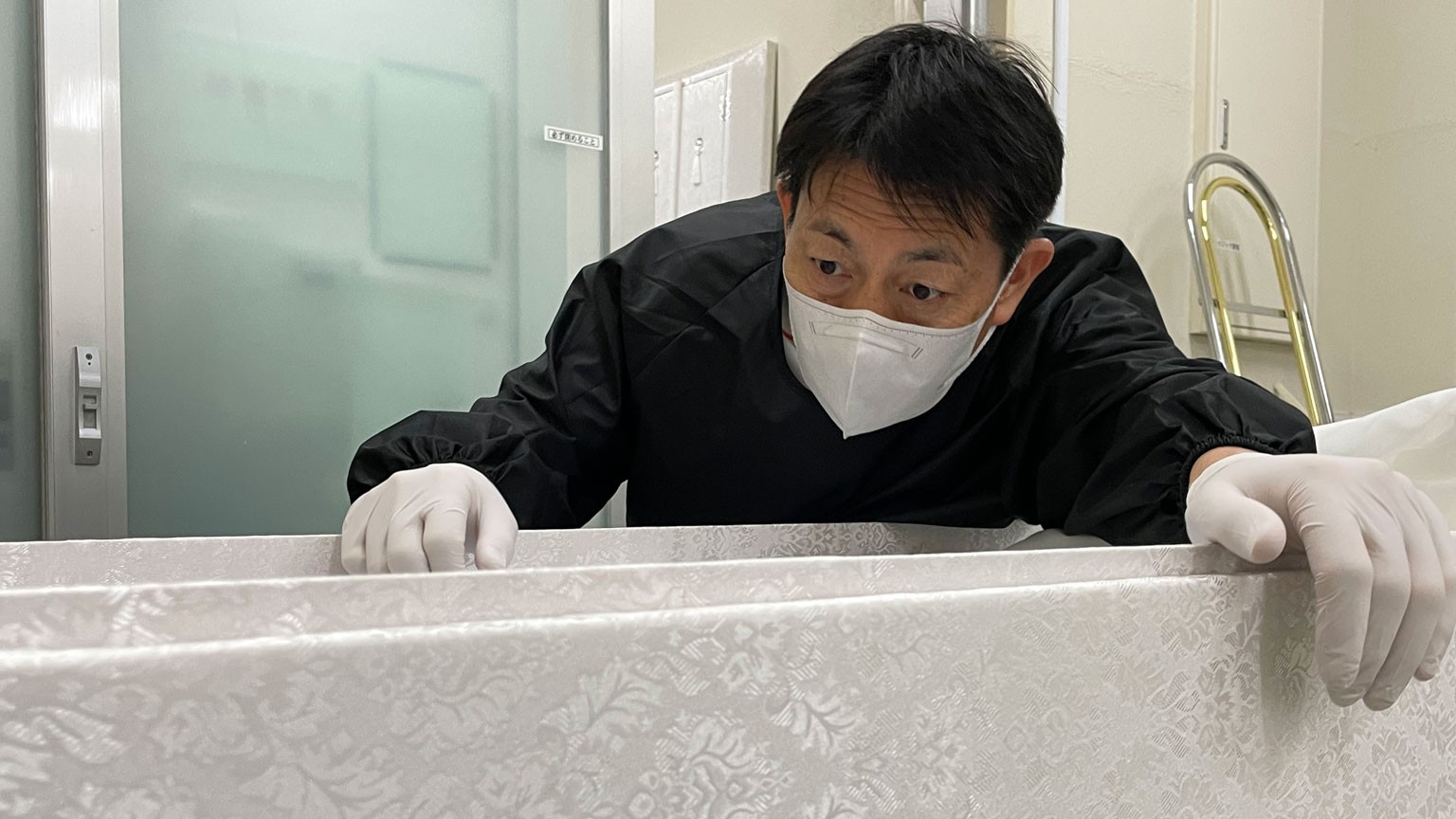

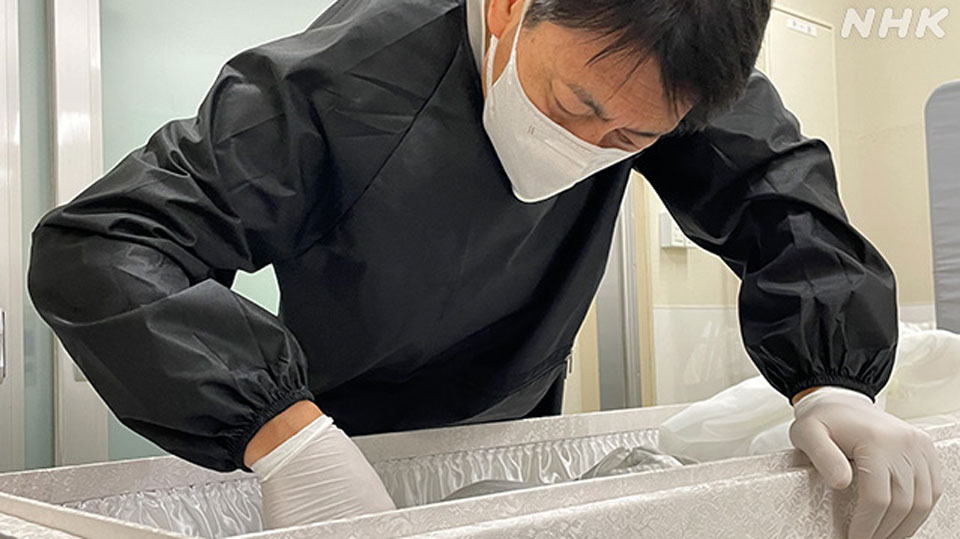

Someya Yukihiro, 56, is the director of a company in Tokyo that specializes in embalming the deceased and placing them in coffins. Embalmers perform a wide range of rituals — including a final bath for the deceased, dressing them in a favorite outfit, rinsing out their mouths, trimming their beards or applying makeup. The restoration process is done subtly to ensure the departed look as natural as possible. But some have changed due to illness, injury, or decomposition.

In those cases, morticians can perform what's known as a special restoration in preparation for family viewings.

Fulfilling last wishes

"I will treat your body now." Someya speaks respectfully to the corpse, and always bows and puts his hands together before getting to work.

He spends a long time facing and contemplating the deceased. During the treatment, he often talks to the corpse.

"Your experience was painful, right?"

"I'll do my best to prepare you for saying farewell."

"I'll make it happen. Please count on me."

Someya explains: "I feel it's our duty to fulfill the wishes of people who see off their departed loved ones. For me, this is a job worth doing."

"I can't say goodbye with his changed face"

Last year, Someya had a difficult case that stands out in his memory. It was a request from the widow of a young man who had been struck by a train. The man's body was badly disfigured. His widow deeply bowed her head, held Someya's hand, and pleaded, "I can't say goodbye to him like this. Please do something."

"I told her that I didn't know how much I could do, but I would do my best to respond to her request with the company's full backing. I felt a strong sense of responsibility," he recalls.

Someya and his team used special wax and other materials, and applied makeup to achieve a natural facial expression.

It took about 20 hours for Someya to complete the work. When the man's widow met with her late husband for a final goodbye, she stroked his head many times and was reluctant to part with his body. Before he was cremated, she carefully took a lock of hair home.

"I want to be able to erase the memory of the bereaved family's first sight of the corpse as much as possible, and to restore the face that remains in their recollections. That's always my approach," says Someya.

Helping to accept death

Hashizume Kenichiro represents an organization that provides bereavement support. He says the work of morticians is vital.

"When accepting the death of a loved one, a bereaved family will accept it with their five senses. Accepting reality is the first step in grief work, and anything that helps with that is important support," said Hashizume.

Frustration with COVID restrictions

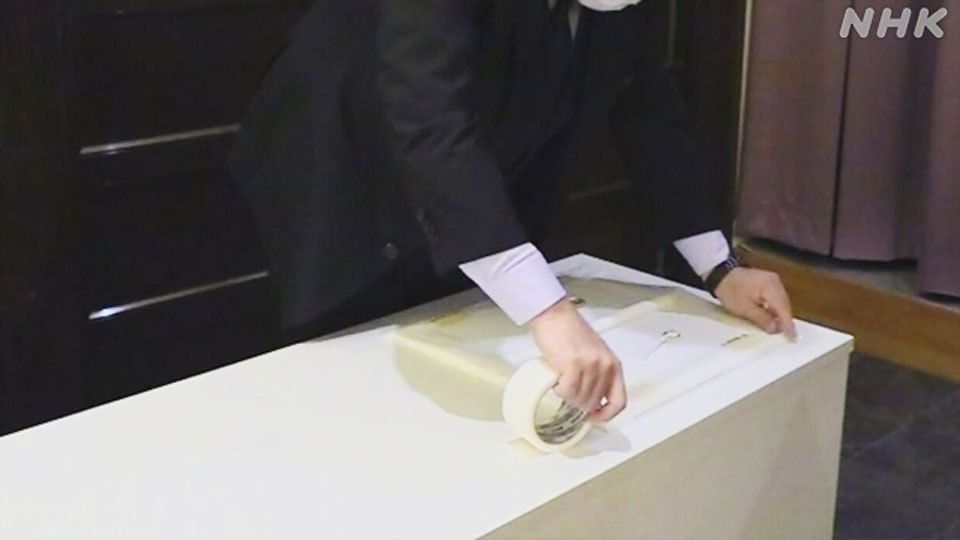

The coronavirus pandemic has significantly impacted Someya's work over the last three years. As part of infection control measures, the government issued a request for people to refrain from touching those who died from COVID-related illness.

That meant that tasks such as cleansing the body and applying make-up were often skipped. The deceased were placed in body bags and then coffins sealed with tape.

Bereaved families could not enter the crematorium, so many cremations took place without loved ones present.

Someya's company has space to store bodies, but capacity was stretched during the COVID era when a nearby crematorium limited its operations. The whole situation upset his fellow workers.

"I can't help thinking this person will only return to the family as bones in an urn. I can't bear to think of this if it were my own family. I want to return the deceased to families through restoration. It is all I can do," noted one of Someya's colleagues.

Doing what they can

Some bereaved families of those who died after being infected with the coronavirus requested makeup and other treatments, saying that they wanted to make their family members look beautiful and see them off.

Initially, Someya's company adopted the maximum infection control measures, such as protective clothing, goggles, and double gloves. But in 2022, when the risk of infection was deemed low, Someya went back to using only one mask and one glove.

At the time, the government's restrictive guidelines were still in place, but Someya felt a duty to do what he could. Even so, the bodies were being placed in bags and sealed in coffins. Their families still could not be there to say goodbye.

The Japanese government reviewed the guidelines in January this year. "Body bags are not necessary if appropriate measures are taken for the corpse,'' states the new rulebook. "People can touch the corpse if they wash their hands well afterwards."

Someday death will come

Someya, who entered the industry in 1992, has witnessed much change. In recent years, economic pressures have popularized small funerals involving only close relatives, as well as cremations with no funeral service at all.

Japan's population is aging and more people die every year. By 2040, the number of deaths per year is expected to peak at 1.68 million.

Someya says that his company has received an increasing number of requests over recent years to work on the bodies of people who died in solitude. To ensure a dignified end, he wants people to think about how they will see off the dead, and how their own end will be.

As part of that, he suggests open discussion: "If you say to your family, 'What if I die?' they usually say, 'Don't say that,'' and that's where the conversation ends.

"But everyone dies. The time will come when both you and your loved ones will pass away. I don't think it's rude or inappropriate to prepare for something that you know will come someday."