The Suenagas spent their honeymoon weeding fields and cleaning out an abandoned school to pursue their dream of creating a safe haven for people with intellectual and learning disabilities. The idea was for newcomers to live and work side by side with the local community.

Big vision for small village

Suenaga Shota, a trained caregiver, found the venue for his vision to start up what he calls Neast Side Experiential Stay in Ichikano village, a 40-minute drive from Wakayama's sandy white beaches.

The facility provides lodging and employment for people with disabilities, and also a café to serve the local area.

Suenaga fell in love with the village's bucolic beauty at first sight, and the old primary school — which closed down in 2017 — provided the perfect setting for his project to provide nature and nurture to those with special needs.

"I began to question if the current system is good enough as it is," Suenaga said. "They are pigeon-holed into very limited choices of work, such as putting this nail in place, or moving parts from here to there. I wanted to widen their horizons with farming, fishing, agriculture. Work to do with the great outdoors."

Given the labor shortage in villages, Suenaga thought bringing in new faces and willing hands would be a welcome move.

But when he put his proposal to the locals, he faced resistance. The average age of the 170 villagers is 70. They were initially against the young couple bringing intellectually disabled people, or people with developmental disorders, to live and work in their community.

Suenaga's proposal was put to a village referendum, which just managed to scrape through: a third disapproved, a third approved and a third sat on the fence.

Finding the right pace and space

When he worked in Osaka as caregiver for children and youths with special needs, Suenaga was painfully aware of the worries of their parents.

"People tell me they worry about how their children will be taken care of after they pass away and want to find a safe haven for them. That's a common concern among parents."

Providing accommodation for Neast Side users was central to the project. Suenaga converted the classrooms into tatami guest rooms. These are also available as vacation rentals.

Gradually, people started coming from Osaka to live and work. Initial residents included those who had graduated from daycare centers, which they have to leave when they turn 18.

Yamamoto Shinya, 20, has been working at Neast Side for a year-and-a-half. He goes home to Osaka on the weekends.

Shinya suffers from a serious intellectual impairment. Suenaga notes that having his own space has improved Shinya's mood and relationship with his family.

Said Suenaga, "At home, he would get violent at times and start kicking people, which caused his family quite a lot of stress. I think Shinya has become a lot more relaxed."

Shinya now gets to try his hands at a variety of work — from helping to make furniture at woodwork, to farming.

Neast Side also gave the villagers, such as Takemoto Hideshi, the opportunity to utilize their skills.

When Takemoto heard Neast Side was hiring, he applied to help with the renovation of the café and making the furniture used there.

He was also interested in the facility for reasons close to his heart. His daughter Airi has mild autism and used to be a hikikomori, someone who withdraws from society.

"Around that time, my daughter had just graduated from a special assistance school and I was wondering what her next step should be. After consulting Suenaga, he said "Why not ask her to come here?"

Since starting work at Neast Side's cafe last March, Airi, now 18, has become more cheerful.

The café serves as a sanctuary for residents to enjoy lunch and laughter together.

Sada Hitomi, a former schoolteacher at Ichikano, said, "Until now, there wasn't a place like this for us to get together, so we seldom had the chance to meet up like this. I'm really grateful."

Rediscovering roots

Suenaga is also actively trying to help Ichikano revive its declining industries, such as the production of "sakaki" — a leafy shrub used in Shinto altars and festivals. Making them is a very labor-intensive process, so now nearly all the sakaki used in Japan is shipped from China. But Suenaga says the locally grow variety lasts longer and has thicker leaves.

One of the few sakaki makers left in Japan is in Ichikano and now collaborating with Neast Side to continue production.

Sakamoto Hiromi and her husband Hidenobu used to handle the sakaki harvesting and bundling process all by themselves.

Then last year, Hidenobu suffered a stroke that left him with short-term memory loss. Fortunately, Neast Side was nearby so Hiromi approached Suenaga for help in caring for her husband ... and also their life work of sakaki making.

Said Suenaga, "I thought we had to preserve this culture. And actually, the sakaki-making process has also helped Neast Siders gain confidence."

This is particularly true for Tsuji Yukina, 20, who has a developmental disorder. She tried working in Osaka, but couldn't fit in.

"I used to work at a bakery, making bread and preparing ingredients," said Yukina. "But I dreaded going to work, and I became a hikikomori. That's when Suenaga contacted me and asked me to come here."

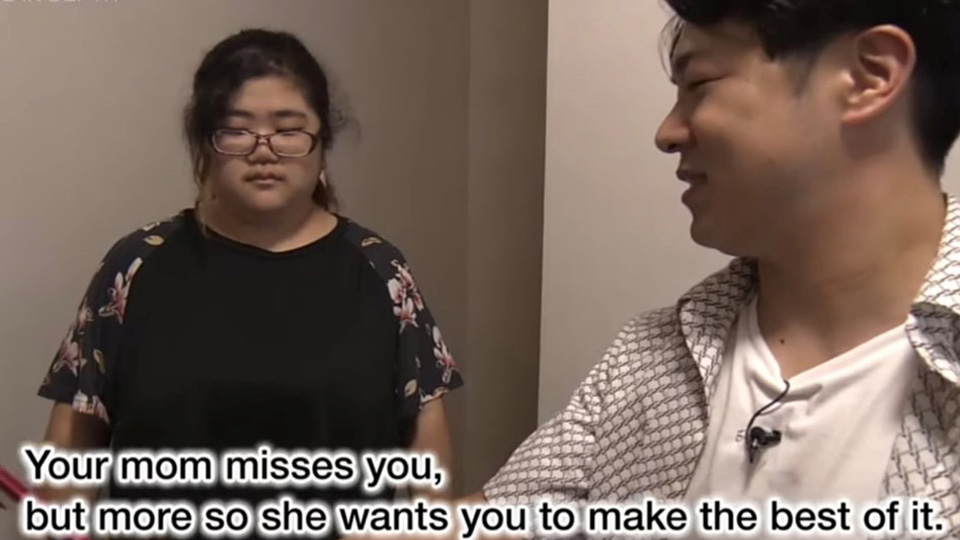

Suenaga has known Yukina since she was a teenager, and thought she would benefit from a stay at Neast Side.

And he was right. Yukina now enjoys the challenge of making sakaki, fit for the Gods.

Hiromi is also impressed with Yukina's progress: "Yukina tries her best to do everything by herself without giving up. I'm really glad that there is hope for the sakaki business to carry on in future."

The Neast Side experience also gave Yukina confidence to live by herself. She recently moved out of Neast Side to her own apartment nearby.

Her mother in Osaka is impressed with her daughter's development at Neast Side.

She told Suenaga, "It does get a bit lonely when she's not around, but I'm glad to see her trying her best."

Yukina says she hopes to gain enough confidence to pursue her childhood dream of becoming a nurse.

She said, "I know it's difficult ... so I want to build on small successes first, by focusing on sakaki making."

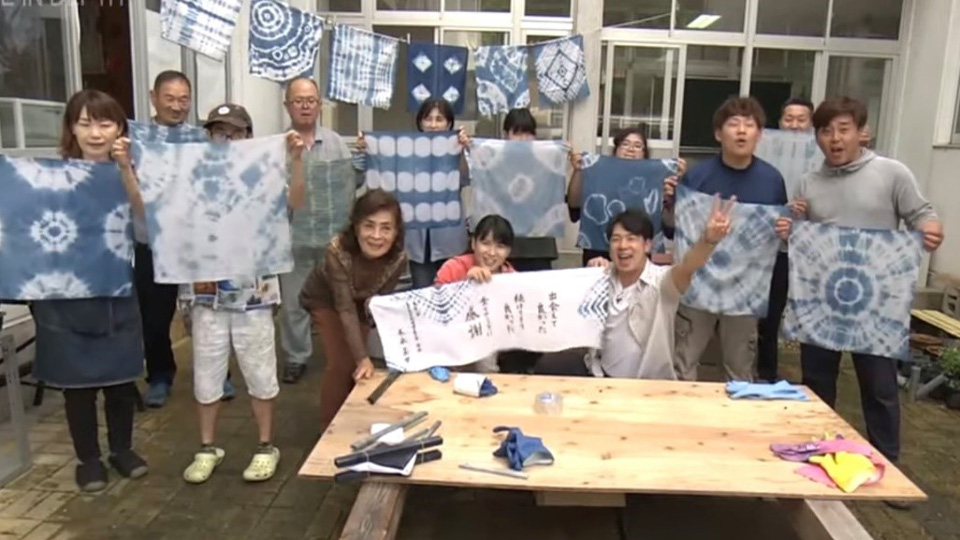

Aizome, or traditional indigo dyeing, is another local industry receiving Neast Side support. The facility is tapping local experts to run aizome-making classes.

Nakamoto Kazuyo, now 88, is a master of aizome.

"I'm so happy that Neast Side is trying to revive the tradition," said Nakamoto. "At first, I was worried about whether such a young person could fit into the countryside, but as you can see, he gets along with all of us. I'm glad he's here!"

Spirit of mutual respect

The Suenagas' commitment to culture and tradition, and to creating an inclusive society is rooted in their everyday practice of the Way of the Sword ... and its spirit of mutual respect.

Mari is a three-time All Japan kendo champion. Her presence has helped turn Ichikano into a popular destination for kendo training camps ... and there are already several summer camps in the lineup.

Slowly but surely, the Suenaga's efforts are helping to create more awareness of Ichikano, and of the possibility of an inclusive society for all to live and work. All it takes, is a village.