Bank of Japan maintains easing policy

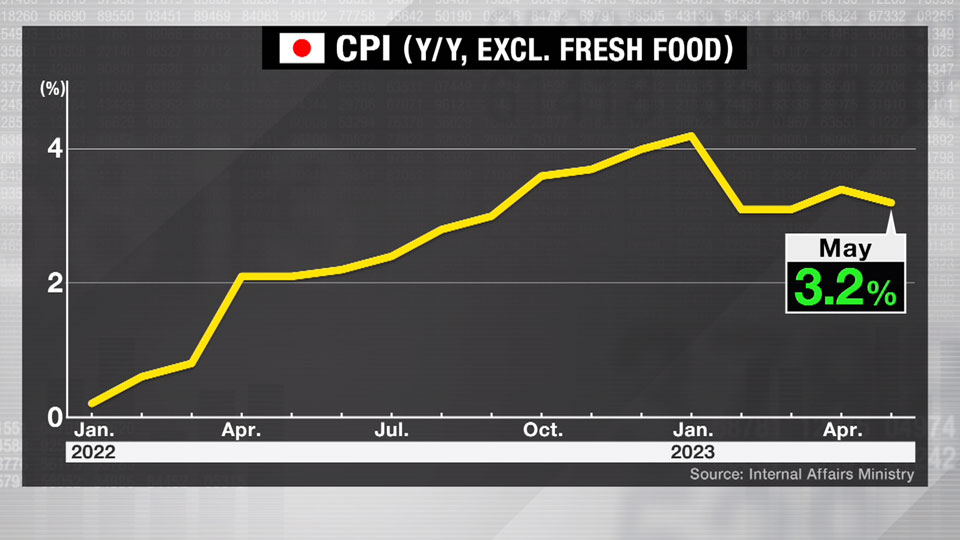

Japan hasn't seen inflation of this level for about 30 years. Its central bank has been struggling for more than a decade to get the rate up to 2 percent.

At its latest meeting held June 15-16, the Bank of Japan decided to continue its ultra-easing monetary policy, even though inflation is above the 2 percent target.

BOJ policymakers say current inflation is driven by higher costs of imported materials due to inflation abroad and a weaker yen.

They are concerned that if the ultra-easing policy is halted, the country could slip back into deflation — and that's why the BOJ is the only central bank among the world's major economies that is keeping its key rate at zero, or even lower.

Inflationary factors

But chief economist at Mizuho Securities, Kobayashi Shunsuke, entertains the possibility that inflation is here to stay, at least for the short-term.

He says the rising prices of goods are beginning to exceed the increasing costs of imported materials, which suggests firms are raising prices not only to compensate for higher costs but to boost profits.

Kobayashi adds that the jump in imported materials costs is forcing companies across the board to raise prices. This makes it unlikely customers will take their business elsewhere to save money, allowing for an overall price hike.

He says consumer sentiment also plays a role. People are now more willing to open their purse strings, because they have money in their savings they were not able to spend during the pandemic.

Wage growth key

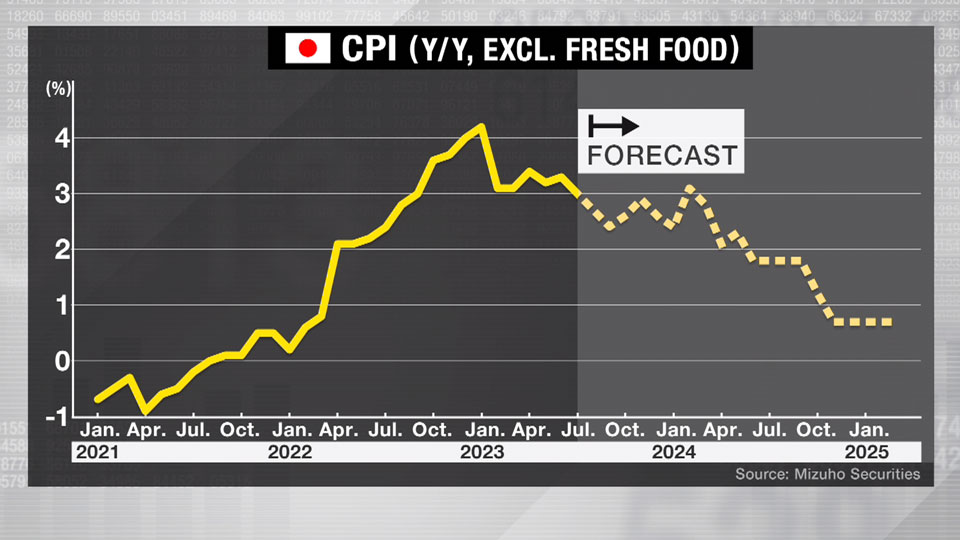

But Kobayashi notes that inflation could fall back down below 2 percent if wages don't rise.

He says the latest average increase in base pay (excluding overtime and bonuses) was only 2.1 percent, which is lower than the inflation rate.

Kobayashi warns this disparity could lead consumers to cut back on spending. And if consumption doesn't increase, companies will no longer be able to raise prices.

Spring wage negotiation

Next year's spring wage negotiation is key. The system, unique to Japan, sees labor unions at major companies negotiate pay rates with management every March. The outcome serves as the benchmark for small- and medium-sized companies.

Kobayashi says the current environment favors the unions. With companies profiting on the back of increased prices, and the labor market growing tighter due to the aging population and post-pandemic economic recovery, the unions know they will be able to make greater demands than usual.

A "sustainable and stable" aim

Kobayashi believes the BOJ has two related aims: for inflation to be 2 percent, accompanied by a wage increase of about 3 percent.

If wages do follow that pace, rising faster than prices, policymakers believe Japan could finally see healthy inflation kickstart a positive economic cycle.