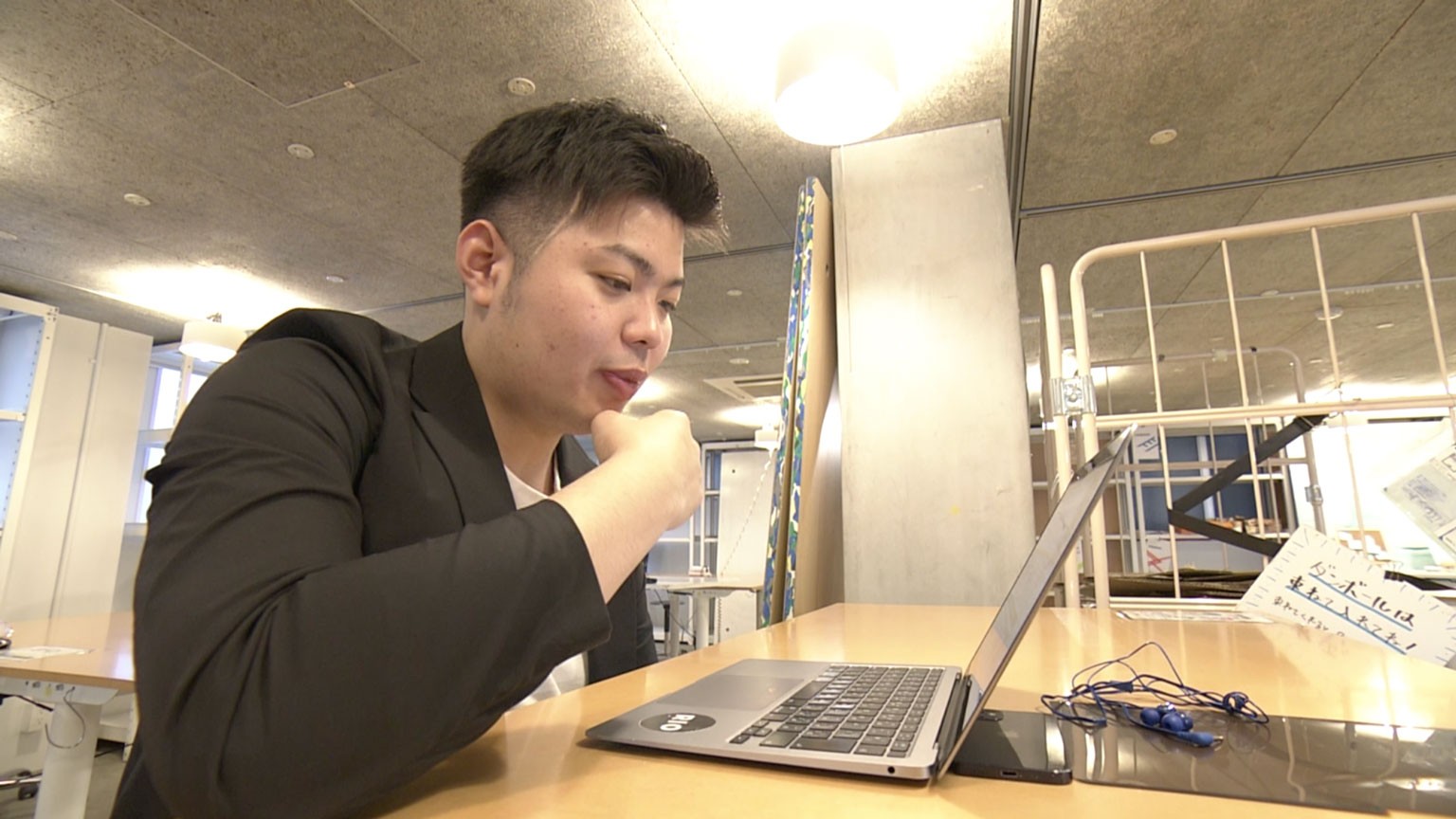

Matsukawa Rikiya recently started offering career-development classes and consultation for people with disabilities. He says he has dreamed of setting up such a service since he was 18.

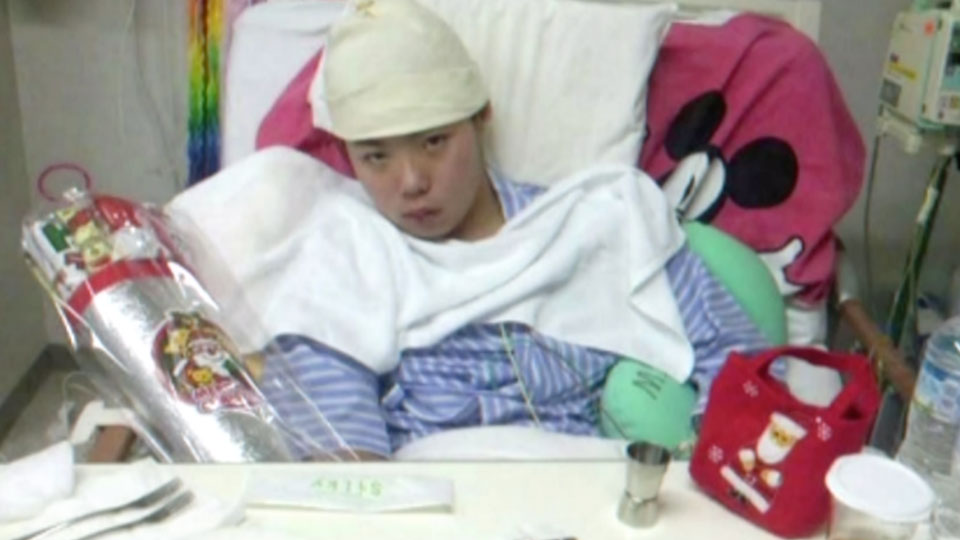

Matsukawa had a brain hemorrhage in his teens, leaving the left side of his body paralyzed. He has since dedicated himself to helping others with disabilities.

Training worth paying for

The central and local governments in Japan provide job-training programs for people with disabilities, most of them free of charge. Large companies, meanwhile, have to ensure disabled workers account for at least 2.3 percent of their workforce.

But Matsukawa thinks a dependence on government programs has deprived people with disabilities of employment opportunities. He points out that the training tends to be basic and prepares people for generally low-paid work.

"People without disabilities spend money to improve their skills," he says. "I want people with disabilities to do the same. You don't have to feel guilty about receiving payment from people with disabilities who want to spend their own money to make their lives better."

Matsukawa interviewed entrepreneurs to find out what kind of skills they value. He used the results to develop a program aimed at making people with disabilities more competitive in the labor market. Along with skills development with a focus on working online, he and his team of instructors help people to craft a career plan.

Matsukawa hopes the program will eventually help push up wages for people with disabilities, which hover at about 70 percent of the average salary.

The job you want, not the one others think you can do

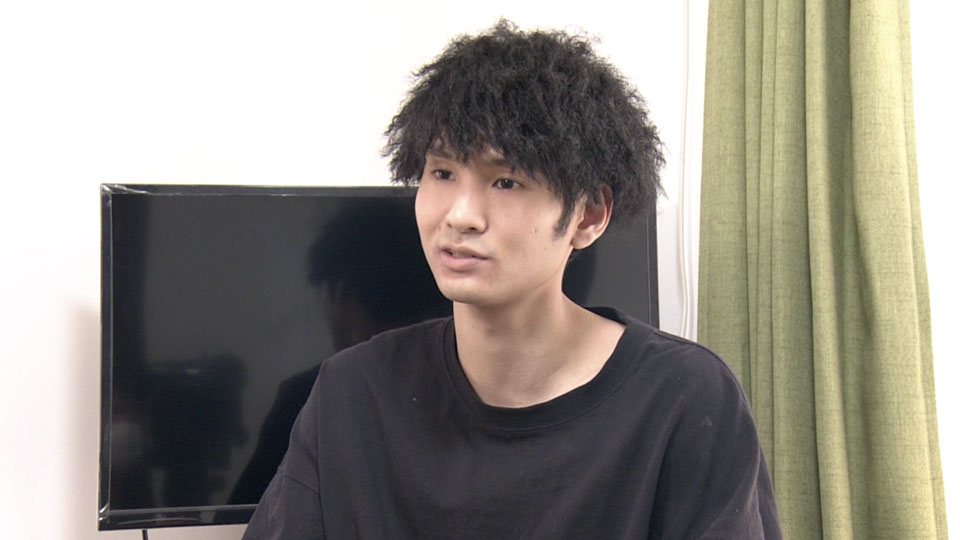

Okawa So was one of Matsukawa's first clients. Okawa was a hairdresser until a spinal injury four years ago limited his mobility. He says he has had trouble imagining a fulfilling career for himself and faces a dearth of opportunities. He found an office job a year ago but was unhappy with the annual salary of about $22,000.

Okawa says the program that Matsukawa has created changed his attitude toward work. He's now looking for a job he will love, rather than one that other people think he should have.

"I have come to imagine myself in 10 years' time," he says. "I have goals like getting a good job and a higher income. Apart from my occupation, I also think about enjoying life. The program not only gave me skills, it also boosted my determination to create the kind of life I want."

After three months of online training he says he has more confidence about what he can achieve. He has a better sense of what he has to offer potential employers as well, including strong IT skills and the ability to work with colleagues to create something special.

One firm is already keen to bring him on board, and the deal is close to being sealed.

Working styles to suit a diversity of workers

The coronavirus pandemic brought much more diversity to the way people work. A vocational consultant notes that the work-from-home trend has led to more opportunities for people with disabilities.

Tazawa Yuri provides consultation services on teleworking. "Large companies willing to hire people with disabilities tend to be in big cities," she points out. "But with the increase in teleworking, businesses in major cities can hire people who for whatever reason live in a regional city or town."

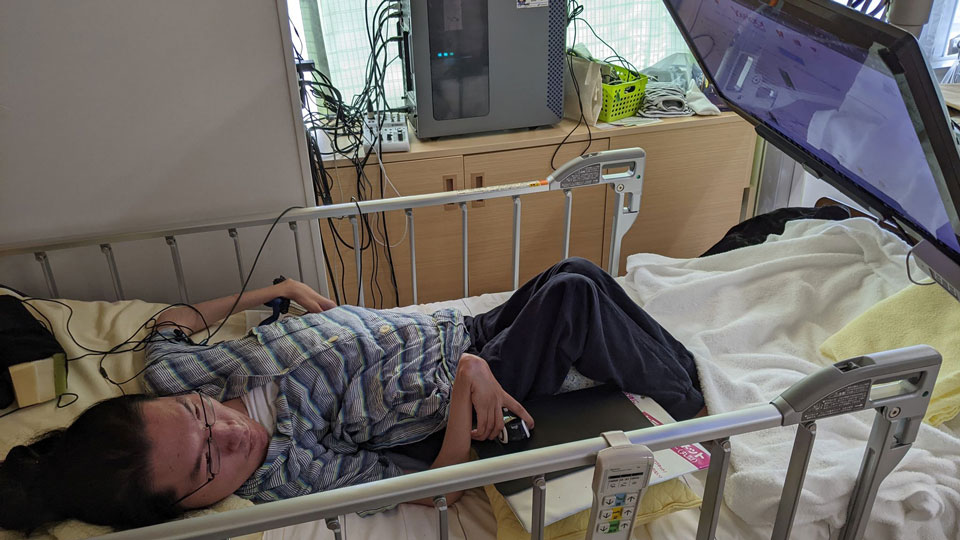

For the past nine years, Tazawa has employed a man who suffers from spinal muscular atrophy. Yoshinari Kentaro has severe mobility issues and is confined to a hospital. He does about three hours of work for Tazawa's firm most days, including producing articles for web magazines and other promotional materials.

"Yoshinari cannot accomplish tasks as quickly as some, but he does excellent work if given the time," Tazawa says. "Companies should assign tasks based on the capabilities of particular workers. That's what they do for employees without disabilities. This allows firms to make the best use of their workforce."

Yoshinari and Okawa are examples of the talent and hard work that people with disabilities can bring to the workforce. Japanese businesses are grappling with a declining pool of working-age people. Along with increased diversity in work styles, this provides an opening for such people to forge career paths that fulfill their aspirations and provide the skills that firms require, all while narrowing the wage gap.